You can spot a packing-noob from a mile away. They’re the person standing outside their new place with six extra large moving boxes, four suitcases, a hodgepodge of loose un-boxable items, and a most prominent expression of sweaty panic. On the other side of the street is the packing-expert, sporting several mid-sized boxes (better mobility), a few trashbags of clothing and odd items (easier to drag in a pinch), complete with a look that says, “I’ve got this.”

The key difference between these two is that one mover’s had enough migratory experience to know that life requires a lot less material crap than we instinctually believe. Human beings are not squirrels. Hoarding an excessive amount of stuff does not help you survive. In fact, lugging around a large stockpile of crap—no matter how much you think those old CD-ROMs might come in handy one day—will only award you back pain. Take only what is needed. Not what means something or what you might need, but what is necessary to not die.

The number one rule for moving out? Get comfortable with the idea of reinventing yourself in your next location. Take your basics, sure. But leave the story that the objects you’ve accumulated tell behind you. Start a new chapter; acquire new stories with new objects.

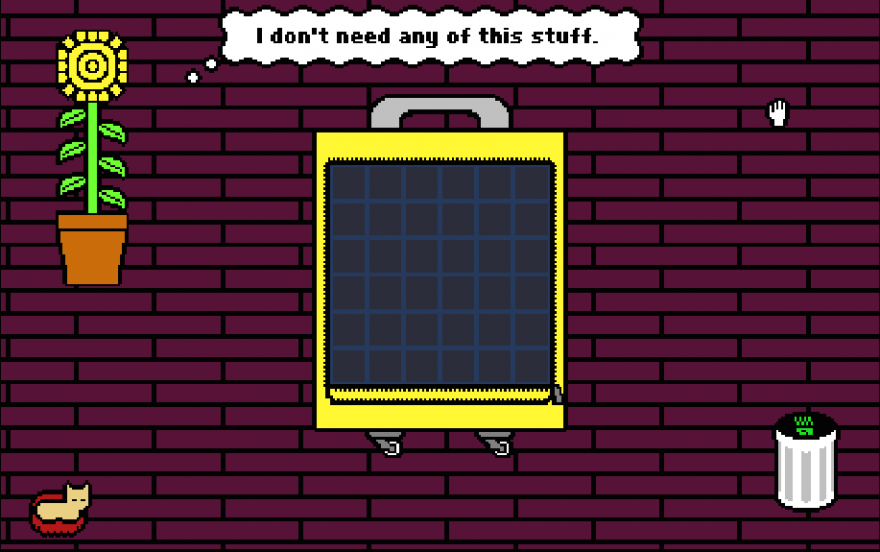

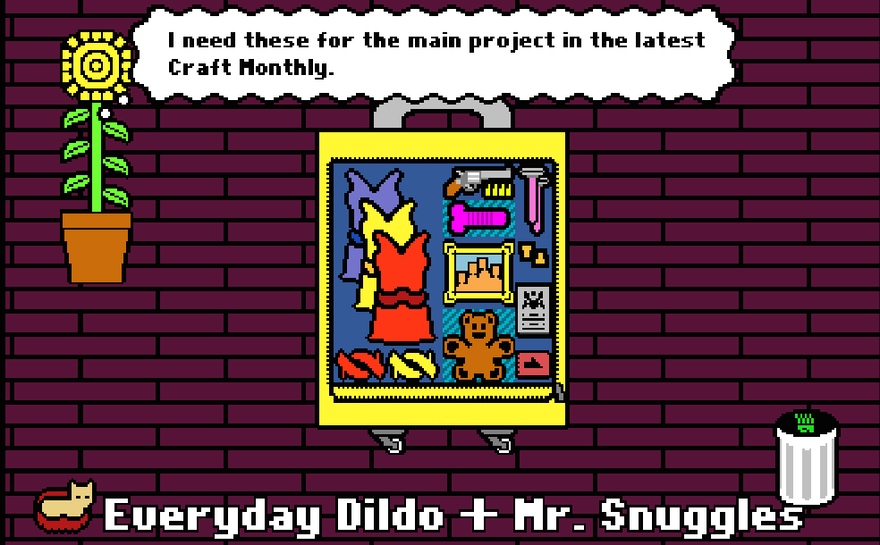

In Terry Cavanagh (of VVVVVV and Super Hexagon fame) and Stephen Lavelle’s (Puzzlescript and English Country Tune) new freeware game Moving Stories, the items you choose to lug into the next chapter of your life literally define the narrative. Many potentially useful items lay scattered across the floor of the protagonist’s apartment: everyday clothes, party clothes, post-it notes, a family portrait, an everyday dildo. You know, the necessities.

But limited space in the suitcase forces you to make some tough decisions, the items you choose defining both the context of the character’s move and the game’s ending. Each time you play, the significance of each item is changed, revealing one in four narratives through the things you decide to take with you.

By providing little instruction to the player other than just “pack,” the objects you instinctually prioritize speak volumes. In my first playthough, for example, I immediately dragged the everyday dildo into prime real estate inside my luggage (wondering whether there was some sort of unlockable “party dildo” to go along with it.) After trying and failing to place the sleeping kitten lounging in the corner of my screen into one of the slots, I chucked the kitty toy into the bin in frustration. Forgoing the everyday option of clothing (because, hello, you should dress for the everyday like it’s a party everybody else just wasn’t invited to), and opting for the Ukelele (as any good alt-chick would), I was ready for the new pastures ahead.

Choosing the party outfits over the everyday earned me the “break up” story. The avatar laments how, now that she and Brad were broken up, she’d be needing to go out on the town more. And while I assumed packing the dildo would help her forget all about stupid old Brad, she also cries about how it had been “Brad’s favorite.”

Next comes the ceremonial dumping of the junk you never want to lay eyes on again. Those items tell tidbits of story too, like how she won’t be needing the earplugs anymore because she won’t be needing to drown out Brad’s unpleasant grunting during sex. The title of the nondescript book I chose not to pack is revealed as Cooking for Two, which should probably be burned instead of just thrown away.

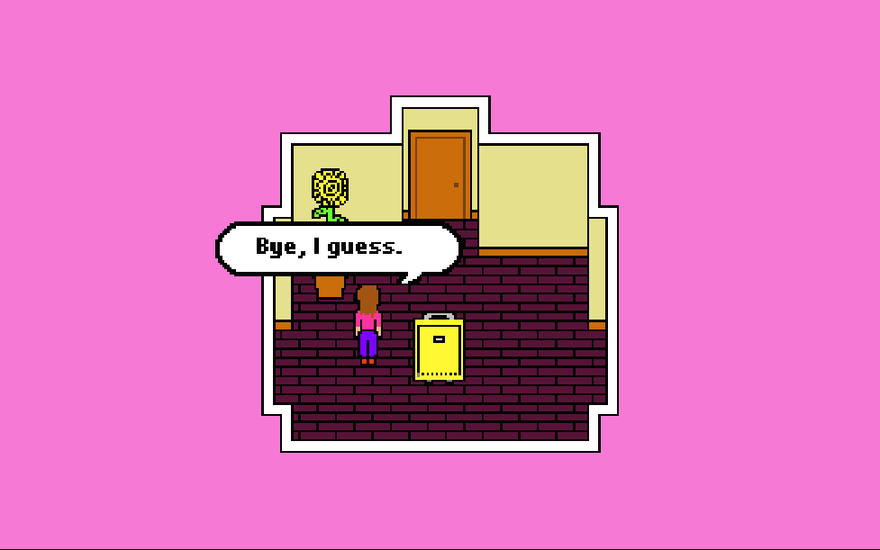

Returning to the apartment, the avatar packs up the last item left in the room: Kitty. Finally, there’s a knock on the door. It’s Brad. He’s here for his cat, and it’s awkward. After he departs with a dramatic “Well, bye,” the cab arrives, prompting the protagonist to grab the tell-all suitcase and walk out the door. For a few seconds, the camera remains on the empty room, and you’re left to wonder what kinds of new adventures she’ll get into outside these walls. Having once lived within them, seeing this exact space day in and day out, it stays behind—barren, after the removal of all the knick knacks that make up human habitation.

Then the Game Over screen appears, and the player is returned to the title screen with a new packable item unlocked. So far, I’ve discovered four possible scenarios, my favorite of which occurs if you pack a suit along with a handgun (an unlockable item). A few constants exist among the different stories: you always need your passport, there’s always a knock at the door before you leave, and your poor cat always gets left behind (or worse). The variables are most telling, though, the most notable being the dildo. The more you pack your pink friend, the less everyday-sized it gets in each successive playthrough. Eventually, mine became so gargantuan that it didn’t even fit in the luggage, prompting my character to wonder if she was “really letting herself go.”

But while half the fun of Moving Stories is tinkering around to discover new endings and easter eggs, that first instinctual pack job persists as the most telling one. The things we chose to carry with us—be it a family portrait or a razor—don’t just weigh us down. They reveal our values and our stories, the life lived inside a space measured in junk.

It really makes you wonder: if that pink everyday dildo could talk, what would it say about Brad?

You can play Moving Stories for free, and explore both Terry and Stephen’s respective discography of games.