Clementine: Hi!

Joel: Excuse me?

Clementine: I just said hi.

Joel: Oh! Hi, hello.

Clementine: I’m Clementine … no jokes about my name.

Joel: I don’t know any jokes about your name.

Clementine: Huckleberry Hound.

Joel: I don’t know what that is.

Clementine: Huckleberry Hound! [singing] Oh my darling, oh my darling, oh my darling Clementine.

Joel: I don’t know what that means.

Clementine: Are you nuts?

Joel: It’s been suggested.

-train scene, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind captured the sublime futility of human relationships like few other films ever have. As a constant fluctuation between knowing another person as deeply as two people can, and realizing that even then you’re still sleeping next to a total stranger, we make lives together not because we are promised happy endings but under the assumption that we will get hurt. The impossibility of knowing each other, understood by everyone and heeded by no one, coaxes us again and again into the inevitable failures of loving another person. The closest we ever come to seeing that other person for who they are is through an amalgamation of constructed and reconstructed memories, the real and not real conversations we have with yourself as we try and make sense of another human being. At best, we manage to understand that person only in relation to ourselves as interpreters.

And there lies the simultaneous beauty and futility of all human relationships. We can’t know each other. But we try anyway. We fall in love with the person our loved one think we are. It becomes a part of how we see ourselves—a part that all but vanishes once (or if) their love runs out. We return to our isolation, to fight another day until eventually we try once again to reach out across the chasm of individuality.

Mike Mezhenin’s game And the Moment Is Gone, originally created as an early proof-of-concept demo created in a Ludum Dare, is a microcosm of trying to breach that chasm. You play as a faceless boy on the subway, struggling to make conversation with the girl sitting next to him. After failure after failure (and a few sexual harassment accusations) you begin to realize just how flawed communication can be, especially when there’s a pretty girl on the receiving end of it.

It’s a scene reminiscent of the iconic first meeting between Clementine and Joel in Eternal Sunshine, which Mezhenin admits was the main inspiration for the game (along with this comic). Like the movie, your character awkwardly fumbles to make any sort of connection. Whether it’s a reference one of them doesn’t understand, or a phrase that accidentally offends the other, nothing is more brutal than the unfamiliar terrain of a stranger’s inner workings.

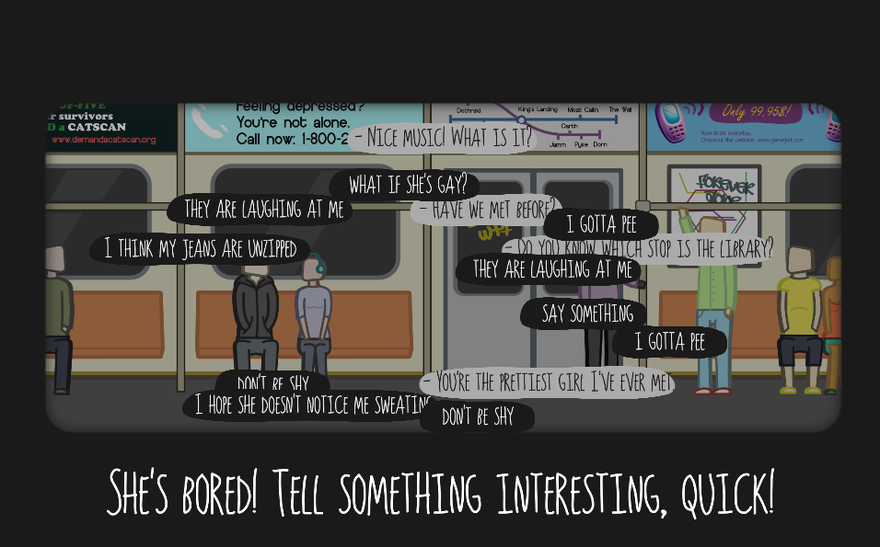

Contextualizing thoughts at the bottom of the screen describe the stages of your attempted conversation. “She’s bored! Tell her something interesting quick!” your character silently coaches himself in a panic. Dialogue options float into existence, as you try to find the responses that suit each situation best, always amidst a sea of “black thought bubbles” that only lead to failure.

Like Eternal Sunshine, the game transforms the seemingly simple exchange of words into a complex battle between your subjective interpretation, the girl’s externalized responses, and the various insecure thoughts that come with trying understand another person. Wether assuming the worst or assuming the best, the black thought bubbles recontextualize many of the exact same interactions, rendering them totally different conversations through just a shift in perspective.

As the creator admits himself in a post-mortem of the jam entry, “I completely failed to communicate the idea of the game being inside the boy’s head—that both ‘bad’ and ‘good’ endings are just his scenarios, and he never actually speaks to the girl.” Though I did eventually pick up on this, the lack of clarity can lead to an uncomfortable first experience. Because if you choose the wrong dialogue options, your lady friend starts politely asking for you to leave her the hell alone. And when the game doesn’t give you the option to respect her wishes, things start to feel pretty darn creepy. Yet as an imagined conversation, the game only tightens its connection to Eternal Sunshine‘s commentary on the complexities of human relationships.

Most recently, And the Moment Is Gone resurfaced as an entrant into the 2015 Independent Games Festival, with some enormous narrative and stylistic improvements. As the trailer demonstrates, our faceless protagonist is now a sweet, mushroom haired little boy, who still continues to struggle to address the needs of interpersonal relationships. Our nameless protagonist (straight-faced Jim Carrey, is that you?!) shuffles aimlessly from an office desk, to a subway car, to outer space with the same apathetic expression. The clear fleshing-out of many of the original demos most interesting concepts, along with the Scott Pilgrim-esque art style, earned And the Moment Is Gone a spot on in our hopeful hearts. And now you can download the full version on Game Jolt to try it out for yourself.