The Thing is one of the most peculiar media series to try and wrap your head around. For starters, as far as series go, it struggles to qualify, mostly orbiting John Carpenter’s 1982 film, with a small and loose assemblage of multimedia offshoots (a comic series, a prequel film) dancing at the edges of its gravity. You could argue that the series itself resembles its titular namesake: an amorphous entity that devours and impersonates the characteristics of its predecessor; each incarnation a diminishing return of success.

Part of the difficulty in capitalizing on The Thing’s clout through serialization is the film’s singular premise. It takes place at a secluded Antarctic research post infiltrated by a dangerous extraterrestrial being. In other words, The Thing champions isolation; set in a location that is perpetually hostile to human life, a group of hapless scientists desperately lash at one another to save the world from the monster that prowls within their midst. It’s an extraordinary film made all the moreso for the particularity of its setting and the frightening intimacy of its circumstances. These attributes render the task of adapting or expanding on the premise of the original film daunting through other mediums, let alone within the shared space of film. So how does one adapt John Carpenter’s The Thing, a film that defies adaptation, into a videogame?

Announced on September 21st, 2000, little less than a month before formal development of the game would begin, Computer Artwork’s incarnation of The Thing was touted as one of presumably many potential forays into Universal’s back catalogue of intellectual properties to adapt into successful videogames. The game takes place in the immediate wake of the film’s events, following two U.S. Special Forces units as they investigate the wreckage of the U.S. and Norwegian bases in Antarctica. You play as Captain J.F. Blake, a dyed-in-the-denim dudebro perpetually nonplussed by the harrowing events of this mission as they unfold. Whether that be being assaulted by a host of skittering human-faced flesh spiders, or the bald-faced revelation of extraterrestrial life, Blake remains stoic.

The game opens with an aerial pan over the derelict remains of the U.S. outpost, underscored by the terse notes of Ennio Morricone’s iconic theme. After being ushered inside by the threat of hypothermia, a cutscene introduces you to the faces of your three starting squadmates, each with their own snappy can-do declaration of purpose. A tutorial prompt takes special pains to assure you that these squad members are “very much alive.” They blink. They fidget. They beg for ammunition. None of their names are spoken.

This strikes at the heart of the inadequacies behind The Thing’s fear/trust mechanic, a squad management system intended to act as a mirror to the film’s emphasis on interpersonal relationships. In Carpenter’s film, Macready, Childs and the rest of the outpost personnel had already cohabitated for several months before the creature’s arrival. The dissolving of their trust and concern for one another is the result of pent-up animosity being brought to the surface in the name of survival. Humanity’s primal distrust of itself in the face of extraordinary duress. But in Computer Artwork’s The Thing, I have no idea what the medic feels about the pointman. I can’t tell if the technician truly believes Blake when he says he’s not infected. And Blake himself is a cipher, his stony exterior absent of meaningful expression. This problem is only exacerbated as the story goes on. My squadmates progressively feel less like my compatriots and more a rotating cast of liabilities, their placid expressions all bobbing in unison, hungrily sapping at the limits of my resources. Perhaps, in some twisted, inadvertent way, there is a genius behind the shortcomings of this mechanic. If I was meant to suspect and resent my cohorts, as Macready and his team so passionately resented one another, wasn’t that result effected, regardless in what way it was achieved? Perhaps my exasperation was the calculated effect of a faulty system. My disdain for these carbon-copy caricatures however serves no justice in recreating the film’s meticulous dismantlement of social hierarchy in the service of terror.

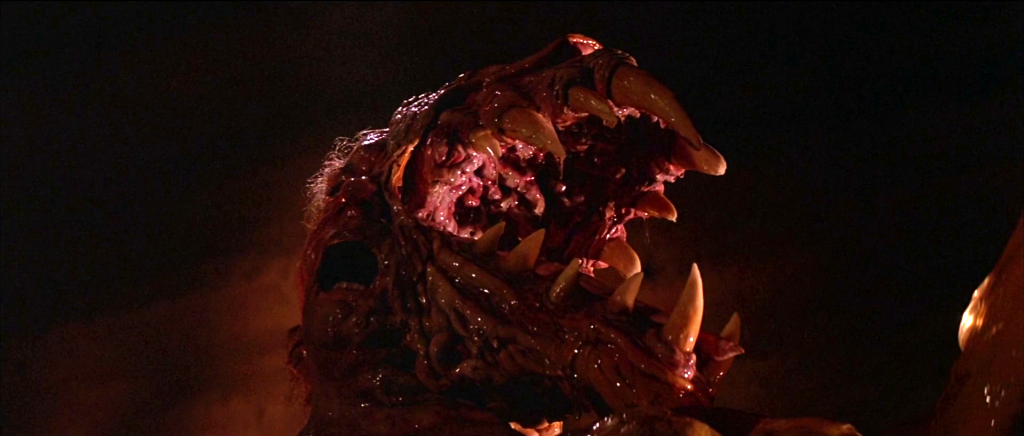

Something sad occurred to me shortly after I defeated one of the game’s larger, more difficult adversaries by circle-strafing, taunting and trapping it in a ring of fire. And that was the salient realization that this game, to put it frankly, just wasn’t scary. The Thing’s ability to infiltrate the strata of the outpost’s physical and social structure was shuttered in favor of monster closets and gallery ghouls. It had abandoned all pretense of coercion, manipulation, and assimilation in the fires that claimed its last ticket to civilization. Now all it wanted was to kill, and the game is all the poorer for that choice. The telegraphed instances where the members of my squad are outed as carriers of the Thing’s parasitic presence feel like a core mechanic relegated to an tiresome afterthought. Where once the creature’s macabre transformations served the purpose of punctuating a prolonged stretch of tension and unease, now they only serve to further underscore the expendability of my teammates. On top of that, the story unfortunately strays from the potent concision of the film’s premise and instead falls on the trope of a conniving corporation hell bent on immortality and a dastardly commanding officer, predictably culminating in your decorated team of stock dudebros pitted against another faction of paramilitary dudebros with the occasional scripted monster encounter sprinkled between.

It is within reason to suggest that the failure of 2002’s The Thing to meaningfully build off of the template of its source material is as much owed to the technical limitations of the time, as they are to the game’s direction. Aside from its role as a continuation of the film, The Thing’s moment-to-moment experiences are typical of that of an otherwise adequate if flawed early-aught third-person shooter, shouldering the likes of Freedom Fighters or Psi-Ops: The Mindgate Conspiracy. The question however persists: If this constitutes a failure, how does one adapt The Thing successfully? One possible approach in capturing The Thing’s signature blend of horror in an interactive medium is perhaps not through slavish adaptation but spiritual emulation.

The Half-Life 2 mod Black Snow, from 2012, is a sterling example of this. You are John Matsuda, an IT technician tasked with a repair team to investigate a mysteriously radio silent installation known as the Amaluuk research station. Things quickly take a turn for worse when your team is massacred by a mysterious presence on arrival and you, wounded, weaponless and alone, are left to fend off the elements and find safe passage back to civilization.

The game is an unabashed homage to Carpenter’s opus; recreating such familiar scenarios as a desecrated dog kennel and a subterranean excavation site while managing to interweave its own intriguing mystery. What it lacks in a character study of the disintegration of untrustworthy relationships it compensates with an unwavering tone of ambiguity. The game offers only a piecemeal explanation as to what the malicious presence that stalks you through the corridors of Amaluuk might be. A presence that, at the risk of over-explanation, is less phantasmagorical body-horror and more Vashta Nerada, the microscopic horrors of Doctor Who.

Carpenter’s original film is tantalizingly bookended by ambiguity. The human inclination to dispel mystery is compulsive, a preoccupation with which is, perhaps, why we make sequels and adaptations in the first place. Explanation is too often confused for resolution; the catharsis of doubt for the conclusion of conflict. But to abide a mystery is to suffer it, to solve one is to destroy it. And so too is a crucial part of The Thing’s enduring appeal stripped away in the attempt to place it as the mid-point in a larger continuity. Black Snow, too, exists on its own; its conclusion offering only a modest understanding of what transpired before our arrival. The mystery, and therein the horror, persists long after our departure.

But perhaps more impressive than Black Snow’s ability to coax the player’s curiosity from out of their comfort zones is its discerning sound design. Many of its primary assets, including sounds, are lifted from Half-Life 2: Episode 2’s pre-existing library. As such, there are the familiar Valve-authored bleeps and bloops, the synthesized death-rattle of a combine soldier co-opted to accompany the hallucinatory static flashes that seize across the player’s line of sight from time to time. But it’s most interesting in its quiet moments. The game relishes these pregnant pauses: the errant flicker of a faulty light installation, the ambient hum of the station’s power system, and the howling snowstorm that rages outside. These sounds form a blanket of ambience that offers, if not a total reprieve, then a temporary moment of calm before the inevitable scuffling pitter-patter of imminent death.

The nature of adaptation necessitates that one or more of the defining features of the original are likely to be lost in the gulf between mediums. This includes staples of the film that may be inadaptable to the medium of games, such as Carpenter’s deft camera-work that, when studied closely, masterfully insinuates a resolution to one of the film’s lingering mysteries; or the grotesque physicality of Rob Bottin’s creature effects design. It bears mentioning, however, that even Carpenter’s film itself is only the second adaptation of John W. Campbell’s short story, “Who Goes There?” Perhaps the interactive successor to Carpenter’s The Thing is not ostensibly an adaptation, but merely a game that knows how to siphon into our collective desire for solidarity, our repulsion to isolation, and our all-too-knowing fear of what waits in the dark.