The Last Game Trader

Fred Schofield isn’t a gamer. The confession comes 10 minutes into an interview I’m recording for public radio. “I’m all thumbs at this stuff,” he tells me.“I can’t even play Mario.” Motioning to his massive collection of videogames and consoles that surrounds us, he says, “This is all to feed Buddha.” Older and sporting a plaid button-down shirt, Fred looks like he’d be more at home behind the counter of the hunting shop across the street. But despite outward appearances, this salty New Englander owns one of the largest stockpiles of used games in the region.

Since 1995, Fred’s owned and operated a used-game store, the Video Game Exchange, from a green canopied shopping plaza in Plaistow, N.H. Sandwiched between a quilt shop and a diner, the Exchange holds the dubious honor of having the most cram-packed windowfront on the whole strip. Brightly colored metal butterflies and lizards jockey for position with neon Nintendo signs and folksy Americana calenders. In the middle of the bedlam is an electric sign that proclaims “Video Games For Less,” a cartoon fist clenching wads of cash just under the bold print.

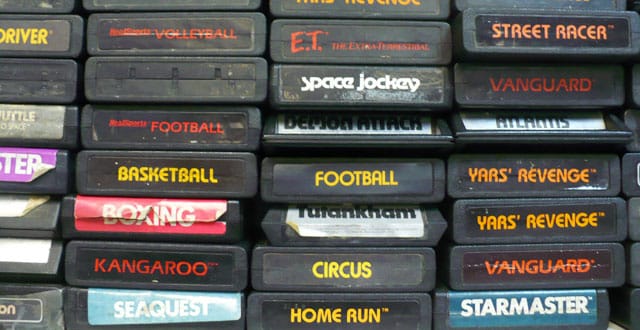

The tacky chaos is mirrored inside. Smudged glass display cases run the length of the store, containing everything from battered NES Zappers and Game Genies to haphazard piles of Dreamcast VMUs. Everywhere are shelves, some of them sagging from the weight of the innumerable cartridges and jewel cases crammed on to them. There isn’t a square inch of the place that isn’t heaped with videogame paraphernalia, all of it marked with little circular stickers with handwritten prices on them. When I ask Fred how he keeps track of his merchandise, he laughs and tells me proudly in his worn-leather voice that “the database is between my ears.”

At last count, the Exchange’s inventory was just shy of 70,000 games. So many, Fred says, that he stores roughly half of the collection in two large shipping containers across the road from the store. “When I open ’em up, it’s getting to the point where I have to duck, because I don’t know what’s in there,” he says. “They’re jammed.”

“Online, online is my problem. I don’t know enough about online. I don’t even like to go online.”

Fred hasn’t always been a game trader. He was an industrial photographer for 25 years, taking pictures of businesses for promotional pamphlets and ads. But by the late ’80s, work dried up: “After a year of going on interviews, you gotta figure nothing’s going to change unless I make it change. I started looking around for a venue to feed myself, more or less, and hit on videogames cold turkey.”

Fred started small. He plundered pawnshops and yard sales all over New England for games, then set up shop at flea markets. “The industry was relatively in its infancy,” he tells me. “I was lucky.” After discovering a company that was buying used games in bulk for double what Fred had paid for them, he found himself in a hectic cannonball run from Portland, Maine, down to Long Island, N.Y., cleaning out FuncoLand inventories as he went. “I had so many games in the trunk of my car that the bumper was almost dragging on the ground. It was a huge score,” Fred says wistfully.

These days, though, Fred is much more sedentary, and the industry much less hospitable to the old game trader. With the advent of the Internet, the Video Game Exchange was thrust into an arena with every other used-games store online. Now in his 60s, Fred admits that he’s unlikely to adapt to the ever-shifting Internet landscape: “Online, online is my problem. I don’t know enough about online. I don’t even like to go online.” The store’s sole AOL email address affirms this.

To flesh out my radio piece, I drive to a GameStop up the road from Fred’s store to interview the employees, and maybe some customers. The contrast is jarring. Instead of precariously stacked walls of Sega Genesis boxes, there are prim rows of neatly arranged DVD cases and alphabetized bargain bins. Sleek LCD televisions peddle pre-order bonuses and exclusive downloadable content. There isn’t a dingy corner in the entire store. Everything has a white, sterile gleam to it.

“I know Fred,” one of the young employees says when I ask about the Exchange. Sure enough, there’s a familiar stack of business cards behind the counter. The employee tells me he refers customers looking for older titles to Fred when he can, but that most people aren’t looking for old games. Two young customers, Cole and Chase, agree. They tell me the oldest games they’ve ever played are on the Game Boy Advance and PlayStation 2. One time, Cole says mysteriously, he played a Game Boy Color.

Despite working in an industry intent on forgetting its roots, Fred feels that his operation still has a place in the world: “Where we have the niche of doin’ classic games, I’m not too concerned about goin’ belly up. It is a unique business and so many people are into the old stuff.” He pauses thoughtfully for a few moments. “They wanna go back to the old classics that started it all.”

Photograph by Jon Lynch