Theresa Duncan’s seminal trilogy of mid-1990’s CD-ROM games—Chop Suey, Smarty, and Zero Zero—have served as a voice for women, and girls, severely misrepresented in media as an audience for only shopping, wardrobe construction, and obtrusive neon typography. Fortunately, these software-based works of art have been successfully preserved on dedicated servers that run the original operating system and software, allowing anyone with a high-speed internet connection to play them in their original context.

Logging on to Rhizome’s main site will effectively transport you back to that time, as you sit in front of the familiar Mac OS7 user interface and experience each game as it was originally intended.

Last Thursday evening, in a rather plain lecture room, in the basement of the New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York City, Mary Duncan, Theresa’s mother, moved around graciously thanking all involved with the project.

Michael Connor, Rhizome’s Artistic Director, also expressed gratitude for the support, specifically for the 463 Kickstarter backers. In introducing the games and why it was important to conserve them, he explained, “You can develop a relationship with [the games] that evolves over time, and each time you return, you understand yourself a little differently, in relation to them, and you understand the works a little differently as your perception of them evolves.”

Having never been exposed to them myself, I was surprised at first by how familiar they felt as point and click adventures, but even more so by how amazingly involved and intricate they were compared to other entries from their era.

In Chop Suey, Smarty, and Zero Zero, you get the feeling that every click has behind it a carefully crafted allegory of some otherworldly significance, or maybe just a clever musing. Clicking on the bush adorned with lights to the right of the entrance to Bob’s House (one of the many Bobs), conjures a beatnik firefly with celestial messaging about its predetermined doom. Dragan Espenschied, Rhizome’s digital conservator, spent a minute or two clicking on a character in rapid succession to make it appear as though he were scarfing down a burger. As he walked us through each game, I grinned throughout at how thoroughly charming they felt.

The panel contained some of Theresa Duncan’s most vocal supporters and friends. Game critic Jenn Frank, whose 2012 article about Chop Suey inspired Rhizome with its need for preservation, Lia Gangitano, a close friend who spoke in depth about Theresa’s character, and Rachel Simone Weil, a game historian who remarked that she “couldn’t think of another kids’ game that had [her] reading books, and researching French history.” Their presentations reinforced Theresa Duncan’s works as games that spoke to girls and not down to them.

The Q&A session at the end sparked an engaging back and forth between producer Tom Nicholson and the panel about whether it was important to remember her works as “girl games” at all. While it was clear that Theresa Duncan intended to address the misrepresentation of girlhood in interactive media, was it reasonable to remember Theresa Duncan’s works not primarily as games for girls? Rachel Weil argued that the games weren’t necessarily only girl games but were different in that they “provided that little slice of relatability.” Jenn Frank elaborated, “Maybe these games are ‘girl games’ only in the sense that they are rebelling against girl games.”

What also jumped out was the absence of discussion on the role that race played in at least two of her works. Both Chop Suey and Zero Zero featured sisters as main characters with varying skin tones and accents. In the 90’s, race in media was very much segregated, such as in the monochromatic television series of both Family Matters and Full House, that featured not only families but entire communities of mostly one ethnicity. Duncan’s work seamlessly depicts people of different ethnicities as family in a way that you don’t see in many other works, unless they are specifically about race—see True Colors. I remembered thinking in my youth that no other family, on screens of any type, looked quite like my family in this very way, and I considered what it would have meant for me had I been exposed to these games then.

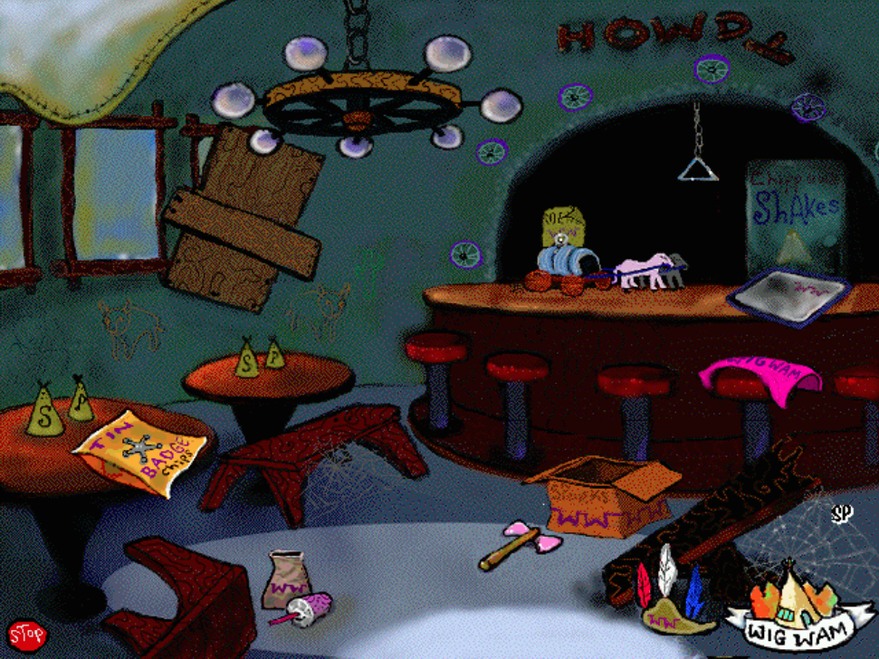

And yet, I’m not sure what to do with Smarty’s desolate “Wigwam Burger” joint, complete with tomahawk and feathered paper birthday hats, the sounds of Chop Suey’s Ping Ping Palace, or Zero Zero’s “Poems of Smoke” caricature Laudebaire. Is her work forward thinking, or is this the substance of an idealized world where race doesn’t matter, from the perspective of someone living in a world where it does? Has elevating her work to star status in terms of its role in the feminist narrative kept us from acknowledging its cheap plays on race?

Perhaps one of the most important reasons for preserving software-based art is to present these ideas to wider, more diverse, and new audiences, for the purpose of perspective. My hope is that Rhizome’s current goal of maintaining the project for just a year is extended far beyond that, so that Theresa’s works could be discovered and discussed—not only by her original or intended audience, but by dissimilar groups of people who might extract untold, untapped insight from her ideas, and even potentially explore the social significance of their shortcomings.

Courtesy of Rhizome, you can experience them for yourself below: