Life’s problems are given a beautiful mystique in WEAVE

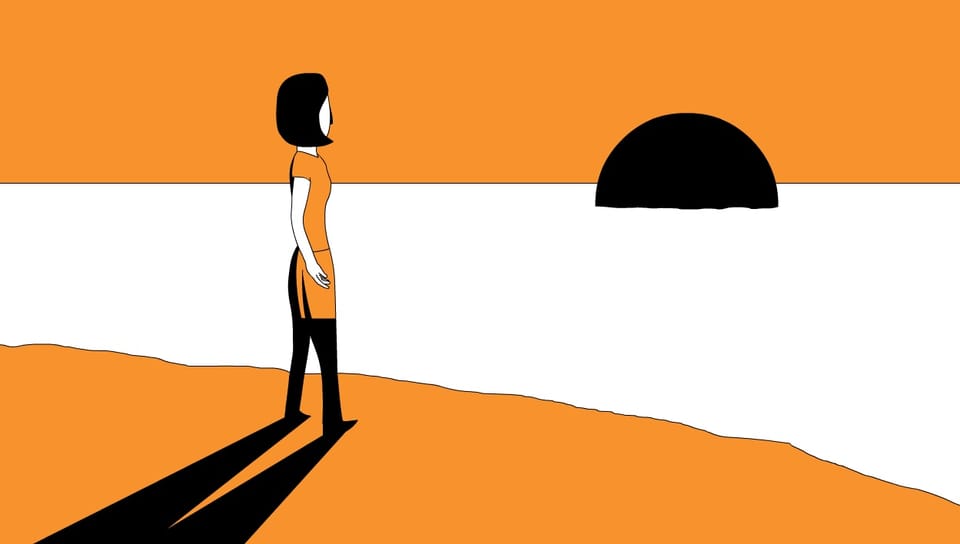

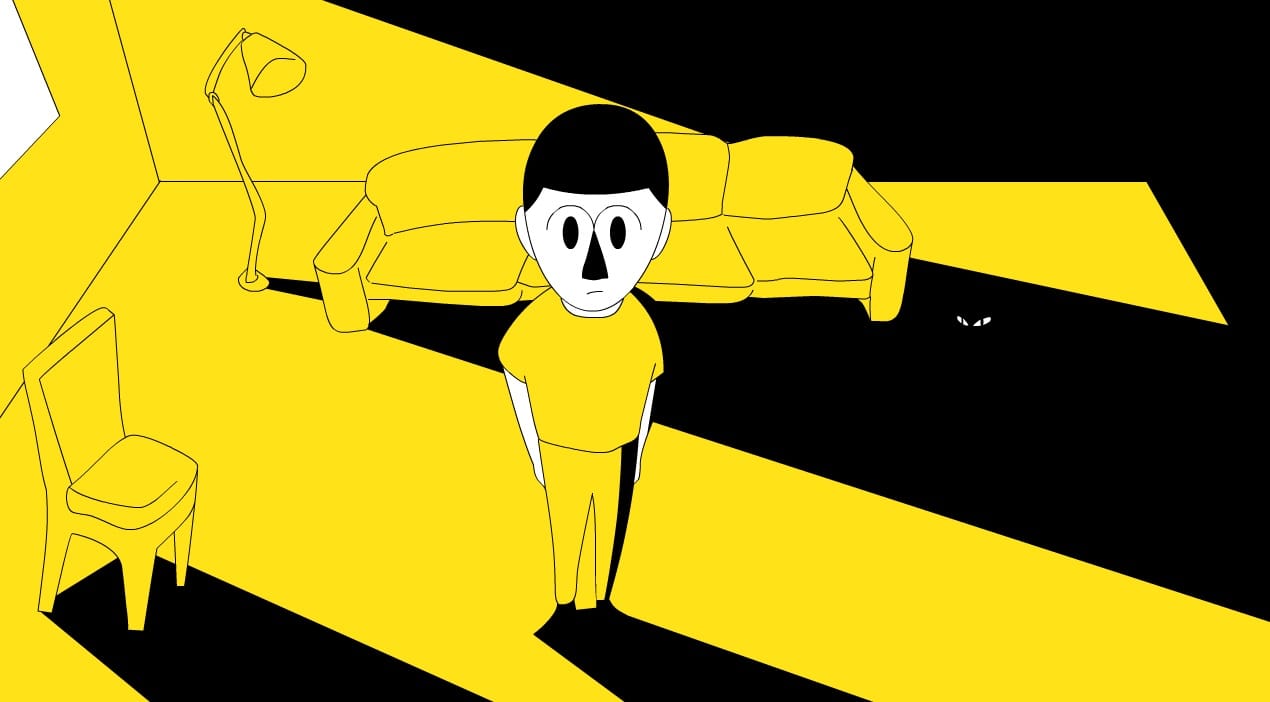

Problems are no longer immaterial in Nadav Tenenbaum’s “abstract journey” WEAVE. They rise up silently from the seas as huge spheres of ebony, blocking out the sun. Or they take up all your living space as unconquerable Sisyphean boulders. Problems cannot be ignored and they will find you.

This is what we’re left to interpret, at least. For Tenenbaum refuses to tell us. That would be counter-intuitive. “There is a thematic structure present, but the lines defining that structure are invisible, and the player must connect the dots to grasp the big picture,” writes Tenenbaum about WEAVE.

something resembling a shared dream.

The game is a rare and beautiful example of the merits of abstract storytelling when combined with the interaction that videogames offer. We know that WEAVE‘s two characters have a problem that they’re trying to deal with. But we don’t know what, precisely, these problems are. We can guess at them but never truly know. Details are obfuscated in favor of playing to a mystique that sees separate events strung together like spilled paint, transitioning not with a logical sense of place, but by whole screenfuls of color.

The result is something resembling a shared dream. Pinches of reality are seen at the start before the characters are stolen by curiosity or a need to escape and taken to the fantastic. One of them becomes trapped in a labyrinthine collection of identical criss-crossing stairs. The other sees the problem sphere morph into a puzzle box that they must solve within an empty landscape. These separate events are joined as one by the use of cross-cutting: each character is given a single interaction or puzzle before it shifts back to the other one, neither character being allowed to resolve a scene in one go, only as a series of interrupted moments. This constant back-and-forth in narrative focus may be what the title refers to.

It’s easy to see how the visuals in WEAVE tell a story even if you have to take wild stabs at what each symbol and scene correlates to. But what about the interactions? It could be argued that they serve nothing else but to give you something to do. It’s prey to the “not a game” argument. And it’s true, you do only click the mouse on occasion, maybe to open a door, or push an object and you have no choice in the matter if you want to progress. There are unquestionably two simple puzzles in the game but what else is there aside from that?

means nothing to us at first.

I’d say that the interactions are there to add our own tangible hesitation to the characters. While the confusion of not knowing what the hell is going on may already make us apprehensive before clicking to progress, the soundtrack adds further fear, it being an ominous ambiance the majority of the time. So when the woman looks at her front door quizzically, so do we, and together we wonder who or what is behind it. The game waits for us as she poses in front of the door, ready to open it, but dare we? She won’t do it without us. But will this next click of the mouse lead to a terrible end for this woman? It’s a risk we have to take. But not until after looking through the door’s peephole.

It’s worth analyzing how Tenenbaum engineers this moment of hesitation. We’ve only just met the woman at this point so why do we care about what happens to her? It’s the interaction that comes before this front door scene that does all the work. After leaving the first character behind in the scene before, the camera cuts, and we see only a black rectangle in white space. As with the game’s storytelling, it’s abstract and means nothing to us at first. Not recognizing anything in this shot, we click to see what happens, hoping to grasp at some comprehension of what we’re looking at.

Upon that click, the camera zooms out as the sound of a piano note rings out. It’s at this moment we realize that we were looking at the black and white keys of a piano, just up close. Click once more and the same happens: we zoom out again, and another note is sent into the air. Upon the third click, the camera changes angle completely to show us the woman sat at her piano. It was a first-person perspective all along, and so, as we played the piano so did she. We shared a playful moment with her. Now we are connected: she is us and we are her. With that established, we see her as somewhat of a surrogate body, and so we might fear for what happens to her. This is when she moves to the scene at the door described before.

You could compare this interactive technique with many other videogames. It’s commonly used to unite the player with the virtual character. And it’s beyond merely matching a button press on a controller with, say, the character jumping. It’s closer to the effect motion controls achieve, which may have us make a downward motion to pull a lever down, or make slashing motion to swipe with a sword. Other examples include Dead Space‘s interface which, as Tiny Design writes, “reinforce the inability to escape the environment,” drawing us closer to the character’s situation and vulnerability.

What’s magnificent about WEAVE is that, to use Tenenbaum’s phrasing, its structures are made invisible to us. The tricks used to pull us in happen without us seeing them. We are transported as if on a magic carpet through each scene, the interactions we make blended with camerawork and a character’s behavior, which allows us to focus on deconstructing the visuals as we try to unravel meaning.