Remaking the notorious PS1 freakout LSD: Dream Emulator

Newcomers to the cult almost always assume that the title refers to the infamous psychedelic drug scientifically known as lysergic acid diethylamide. That much would seem obvious given the game’s illogical tapestry of the eccentric, disturbing, and nonsensical. But the presumption is wrong, that much is known, as in the opening sequence the “LSD” in the title is swapped out for phrases such as “in Limbo, the Silent Dream,” and “in Lunacy, the Savage Dream.”

///

Despite the rise of the first-person exploration game in the past few years through efforts such as the poetic Dear Esther, the musical Proteus, and the forlorn Eidolon, the genre—if you would go so far as to call it such—has yet to outdo the bizarro bricolage of its 16-year-old predecessor.

It’s called LSD: Dream Emulator, and it was released in Japan on the PlayStation back in 1998. Appropriately, its outlandishness and limited release caused it to slip under the mainstream banner of videogame releases that year, much like the suppressed desires of the id streaming below the authoritative highway of the super-ego. The resulting obscurity is what has enabled it to acquire avid, cultish fans.

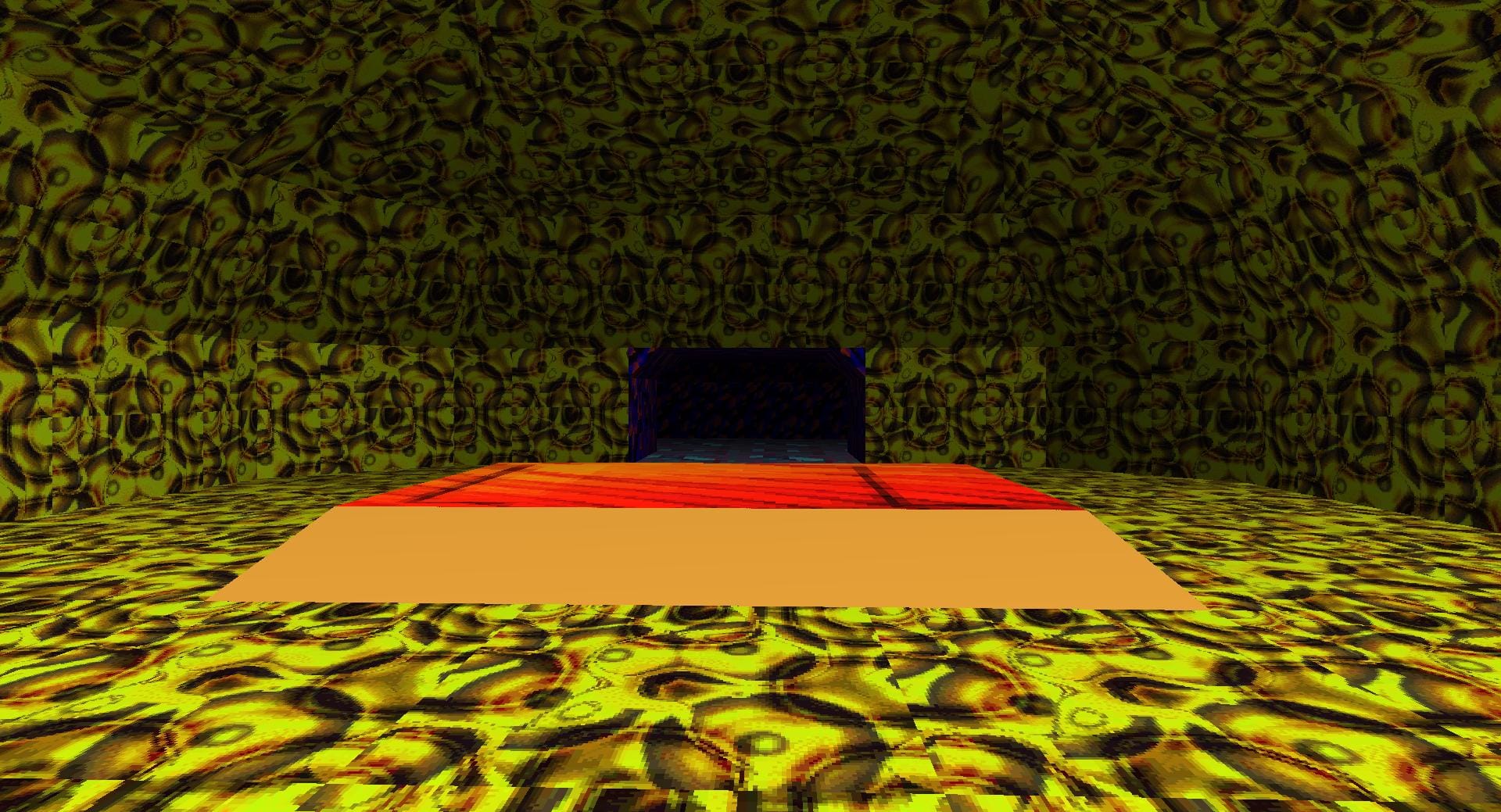

causing walls and floors to transmute into garish repeated textures

LSD: Dream Emulator is a latent work that unwraps as you play it across several short sessions, steadily, strangely. It consists of many idiosyncratic dream environments rendered in low-poly shapes and frazzled textures. The console’s poor render distance means that a gloomy mist hangs at the edges, always hiding what lays ahead. Each step you take is highly telegraphed with a bouncy view and the distinct sound of the material under foot: the crunch of snow, the tap of a wooden bridge, the echoing thud of a steel canopy.

All of the environments are connected non-sequentially and can be aimlessly wandered across, or instantaneously travelled through by walking into animals, body parts, and random unmarked walls. There are renditions of Kyoto at night where the city’s buildings silently glow with electric from behind high fences. Claustrophobic multi-storey mansions hide wallowing fat men that engulf the breadth of entire passages. Railway tracks create borders in voidscapes upon which blocky trains with tortured faces puff nonchalantly. Japanese temples re-occur many times, sometimes populated by TVs and ecstatic teddy bears, or looked upon by despondent unmoving sprites.

No matter what happens, dreams end after 10 minutes, or if you fall into a gorge, at which point you’re sent to a graph of your psyche. This varies between four states depending on the feel of your past dreams: upper, downer, static, and dynamic. The number of days is also tracked, increasing with each dream spent, with higher numbers causing walls and floors to transmute into garish repeated textures, especially of staring faces, but also into swirling shades of disjointed shape and color.

Before long, abyss demons pay a visit, limp bodies of women hang from lamp posts in a dark empty city, and an entity known as the Gray Man is spotted dragging the dread of everything with him. He interrupts dreams with a sudden flash of blinding light and the words “You Forgot,” at which point players are prevented from revisiting that specific dreamscape. The Gray Man is an oneiric motif, acting as if a vengeful ghost haunting the software. He works against the years-long efforts of players documenting the seemingly random happenings inside the game, drawing lines between recurring characters, the degradation of each environment, and the meta game that implies a connection to the human psyche.

LSD: Dream Emulator was born from the dream journal of Hiroko Nishikawa, which she kept updated for a whole decade. Her dreams and descriptions of them were vivid. But it wasn’t until one of Nishikawa’s co-developers at Japanese studio Asmik Ace Entertainment got hold of the journal that the idea of it being translated into a videogame arose. That colleague was Osamu Sato, who had released Eastern Mind: The Lost Souls of Tong-Nou a few years prior—it has since been accepted by many as one of the most unnerving and unpredictable weird videogames ever made.

While Nishikawa and Sato’s heralding masterwork has gone mostly unnoticed over the years, its fans cling desperately to it as time renders it more and more inaccessible with each passing year; the result of the ongoing lack of any widespread effort towards video game preservation. Even its re-release on Japanese PSN in 2010 is steadily becoming outdated. But there is a saving grace.

there is no attempt to upgrade the graphics or usability of the game.

One fan of the game started creating a faithful remake called LSD Revamped back in 2011. He had to learn how to use the Unity Engine from scratch, and abandoned the project for months at a time, so it has been very slow going. Nonetheless, he recently released the first public alpha to collate feedback and show his progress so far. It’s not a bad attempt. Among the most laudable efforts of his recreation is the ruggedness of the pixel textures; they become confusingly kaleidoscopic when you run your face up alongside them. He’s also managed to link the worlds in the same illogical and unexpected fashion. And the walking has the same distinctly confident and loud step.

What is missing is the original LSD‘s infrequent denizens; the haunting entities, the somber inhabitants, and those characters that were toy-like in how they pranced around. And, as some fans were quick to point out, smaller details such as the enclosing draw distance is yet to be implemented. What’s interesting about this remake is that, unlike similar projects of late, there is no attempt to upgrade the graphics or usability of the game. That would be completely against the point. It’s important to these fans that the coarse visuals and kitschy feel of the original is captured, as if it were a steadfast recipe to an arcane ritual.

In a way, it is. The anachronistic haziness belongs to the limiting PlayStation hardware and plays into the unique mystery of Sato’s disparate 3D spaces, which begets its esoteric following, and therefore plays an intrinsic role in any remake. So this is a project that exists not to make LSD: Dream Emulator more widely accessible, at least not primarily, but to add a few more years to its life so that its surreal enigma may continue to entertain the most avid fans for longer. And it’s going to take a whole wealth of shared understanding to make it happen.