Kara Stone has recently taken up gardening. Her floral dependents—Echinacea, sage and geranium—have only grown as far as big sprouts, but she finds the activity grounding in a corporeal sense. This is becoming rarer and rarer in a world where we plant ourselves in front of glowing screens for most of the day. It’s worth noting that Stone is familiar with that disconnection after the hours she spent putting together her first game, MedicationMeditation. It’s also worth noting that she’s planted these seeds in discarded antidepressant bottles.

“When I was making MedicationMeditation,” she says, “it had all of these ideas of focusing in on your body, but I was sitting there zoning out in front of a computer, snapping back into reality five hours later, shoulders up to my ears, dying for a cigarette. No idea what happened, other than that I just ended up with something on my computer.”

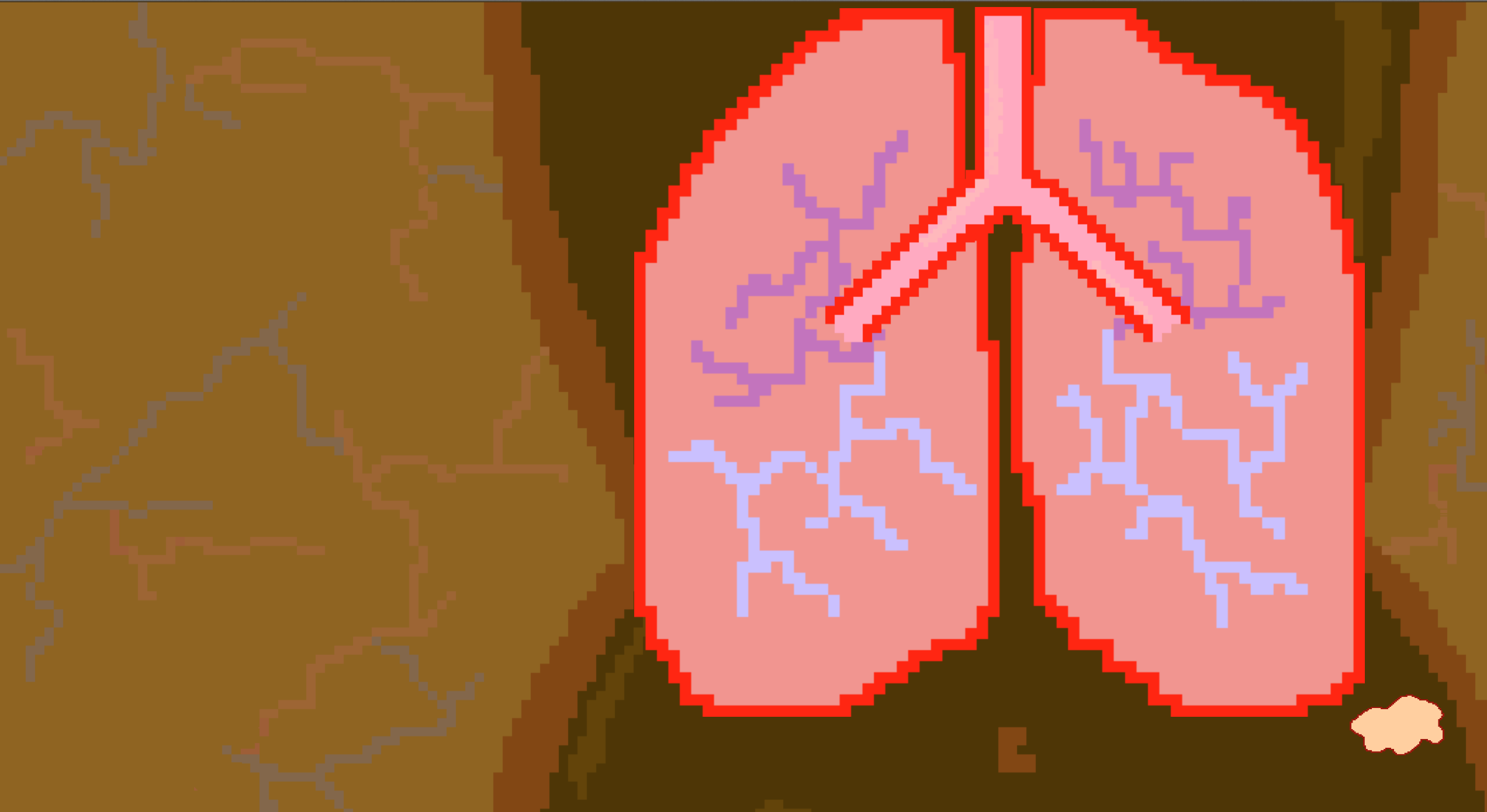

Though making it caused momentary negligence of her own, Kara Stone’s game, of sorts, seeks to make the player conscious of her own body. Flesh-toned, pixilated and stamped with references to the human form, MedicationMeditation is an unwinnable compilation of activities.

There are five, at the moment, which deconstruct and recreate rituals familiar to someone living with mental illness. “Breathe” asks you to align yourself with a pair of animated lungs, inhaling as you click down, releasing while you hold. You repeat the process 20 times. In “Take,” a clock spins round and round, and you are tasked with taking a dosage at required times. (Stone says she knows from experience now unpleasant missing this is.)

“Affirm” is, in ways, the most unusually morbid of the lot. Phrases like “Today I did the best I could do” scroll like karaoke verses on to a forearm as scratches; you’re encouraged to read aloud. “Think,” says Stone, was the most daunting in real life: trying to keep tally on the number of ideas that whip by her brain in a minute. “Before I got into meditation,” says Stone, “that first sitting down and listening to how many thoughts your brain, or my brain, has in a minute, noticing all these half thoughts and jumbles, is excruciatingly painful.”

And finally there is “Talk,” wherein a therapist is represented by a disembodied ear and you are a mouth. She stresses this is in no way a replacement for an actual, professional session. “I didn’t want it to be a self-help game,” says Stone. “It’s supposed to be more about personal experiences of people doing these activities. Me saying an affirmation to myself ten times is not the most pleasant experience. You really are trying to etch it into your body. Bodily remember this thing. I didn’t want to whitewash terrible mental experiences, and cutting is a huge thing with women, even cutting in words. But it’s still playful, I think, a playful way of taking on mental trauma.”

Kara Stone says she’s suffered from anxiety, depression, and had a brutal peak a year and a half ago. It was then she began seeking medical attention and going medicated. While videogames have served as a refuge for her, today she has a hard time returning to Guild Wars 2 and other MMOs because of the associated emotions.

Videogames, escapist as they may be, are not impenetrable from outside anxieties. She can’t come near The Last of Us due to a specific discomfort with alien objects protruding from the human body. Making games comes with its own pressures too.

MedicationMeditation was developed for the Dames Making Games program, though it wasn’t always her intention. Intimidated enough by making her first game, the MedicationMeditation concept was shelved because her peers were pursuing more conventional, “game-y” games, and Stone tried to work on a sidescroller about eating disorders. Eventually she gave in to her disinterest and made a game that cannot be won.

Most games end, but mental illness does not. You do not defeat it, but you learn to manage and live with it, and creating that ecosystem is different for everyone. Kara still seems to be figuring hers out, experimenting with new activities she enjoys—gardening, meditation, videogames. It also consists of therapy and medication. MeditationMedication is about making a routine, not a means to an end.

“I didn’t want to make a game that was like Depression Quest,” says Stone, “where you’re putting yourself in a situation of someone with mental illness, where you’re trying to explain it through somehow distantly being it. Instead, this is doing some things that some people with mental illness have to do on a regular basis.”