Remember the Gamecube’s wonky, bizarre Playskool controller? Three buttons—tiny red B and the gray crescents of Y and X—arrayed around the massive green A button like silverware around a plate. The triggers, L and R, deliciously clicky; big chunky buttons with satisfying give to them. The purple Z button, tucked away on the shoulder. And the analog sticks: one plain gray, one yellow and strangely small.

It was as odd as the console itself, a small purple cube with a handle, as if Nintendo envisioned a future of console-as-accessory. If the Gamecube was futuristic, it was the candy-colored future of pop surrealism, of Takashi Murakami and Juxtapoz: and its figurehead was bounty hunter Samus Aran, whose multicolor power armor and gunship in the likeness of her helmeted head fit right in with the ‘Cube aesthetic.

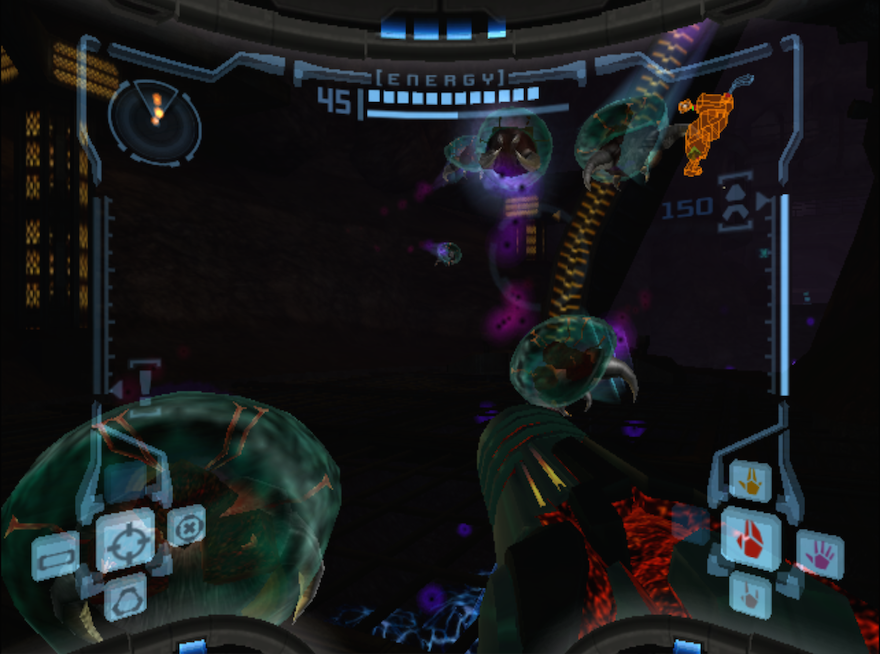

Metroid Prime looks like a first-person shooter. You’re seeing through Samus’s eyes, peering through her visor, navigating her body, but the game isn’t about shooting: combat is as easy as clicking L to lock-on and hammering that big A button.

Instead, mechanical pleasure is derived from movement. Absent any precision-related challenge, shooting becomes about positioning Samus: locking-on with L and tapping the B button in between shots to leap sideways out of harm’s way, or circle-strafing an enemy to expose its weak spot while keeping an eye on your footing.

That clicky, noisy Gamecube controller lends gratifying snap to these encounters. The L button thunking into place leads the player into the dance between A and B, with the occasional tap of Y, above. Unlike most shooters, there isn’t a dual-stick setup—that is, the usual arrangement of two analog sticks used to move a character through a three-dimension space. The C stick, instead, is used to swap weapons with a flick while the other stick is used to move Samus like a tank. Free aiming is possible, but in combat wholly unnecessary.

In fact, the only reason you’d want to freely aim is to explore: in this game, exploration is handed the toolset of combat. This is not to say combat is an afterthought, but that the design of the game plays off the strengths and weaknesses of its mother console. The analog sticks on the ‘Cube are too offset for precise shooting (a problem the Nintendo 64 also had, with its strange three-pronged sex toy shape that demanded allegiance to either the D-pad or the analog stick). There’s a missed opportunity for another left shoulder button. The A button takes up too much space: the face buttons on a Dual Shock or an Xbox pad are neatly symmetrical little circles. The Gamecube controller says fuck that. Meter, pitch, tempo are thrown out the window in favor of idiosyncrasy. Somehow, Metroid Prime twisted that colorful chaos into usable functionality.

Despite the cannon on her arm, Samus is something of an archaeologist in Prime. Scanning enemies and the environment are the most important actions a player can take: outside the information gleaned from Samus’s scan visor, the game does not explain how to take down enemies or solve puzzles. Observation is thus placed before action. Ascending a moss-covered chamber necessitates scouting the area, looking for obstacles before beginning the climb. Taking down a massive creature means scanning first, before shots are fired, to learn that it hyperventilates after attacking, giving you an opening.

Making sense of Tallon IV, the planet Samus crash-lands on at the game’s start, means translating the inscriptions left behind by the Chozo, Tallon’s long-dead inhabitants. These bits of text are poetic, resigned, often mournful. They are the fingerprints of a civilization brought to ruin, the scraps of once-vital life. If Samus is a Ripley-like heroine, a decisive woman hunted by an extraterrestrial beast (named Ridley, no less), than Tallon IV is that brief planetary exploration from Alien writ large.

Prime understands the ambient, haunting power of Alien was born of a fascinating world and the temerity to say as little as possible about it. The game trusts the player’s wits, that she can find her way through inhospitable terrain without incessant prompts, cutscenes, and dialogue to shape the experience.

Instead, the story is written through your actions. How much does Samus learn about the Chozo? Is she lithe and agile, or does she stumble and curse her way through obstacles? Alien was a 70s-horror haunted house walkathon given an extraterrestrial makeover. No one would call it plotty. We immediately know who Ripley is from the way she sits with one leg up on the bridge, her Chucks prominent in the frame. And we become Samus when the brilliant burst of an explosion flashes her reflection on the visor: eyes hard, brows set. That look of determination pulls us in. The narrative thrust of Metroid Prime is simply the impetus to look, and the controls reflect this. There’s always something else to see.