NES Remix transforms classic games into something sinister

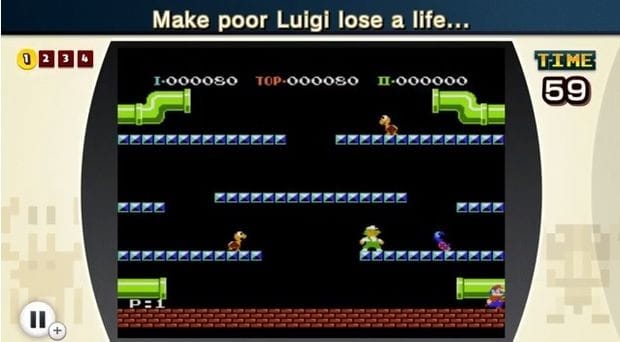

NES Remix pretends to be a simple game. In essence, the title breaks down a dozen early NES games into their individual parts and lays them out, buffet-style, for your noshing pleasure. A “level” in Super Mario Bros. asks you to “Collect the coins!” or “Defeat the Goomba!” Once you run forward and do just that, a ring sounds, as one might at the end of a boxing match, and the action stops. Some levels are a single round; others are a series of rapid-fire moments, one after the other. You’re given a score of up to three stars based on how long you took to complete the sequence. The more stars you earn, the more games and levels open up.

But this simplicity veils the cumulative effect. Remix feels half-antiquated, half-cutting edge. The game on a whole feels ripped from the pages of smartphone app design: Tiny missions, unlocked through play, with plenty of juicy reward for the smallest accomplishment. And yet the mechanics themselves were born three decades prior; each game released in 1985 or 1986, though many were originally developed in 1983 for the Japanese release of the Famicom. In this way, here is a condensed vision of what “gameplay” looked like at the birth of the console age.

There are two ways to view this time capsule. Glance at these Ur-games and smirk at how far we’ve come… …but hold that gaze a little longer and you notice a dense playfield unadorned by extraneous, modern-day fittings. Remix teaches by way of example. A game’s complexity is uncovered node by node. On the surface, Excitebike looks to a newcomer like a stripped-bare version of motocross. You accelerate, use turbo to go faster, and steer. But each mini-level here acts as tutorial to advanced moves never fully disclosed in the game proper. Use your back wheels to send other racers crashing. Lean forward during jumps to gain needed speed. Pop a wheelie to roll over obstacles unscathed. Each title unspools thusly, much like a cooking show separates the finished meal into step-by-step instructions.

Such in-game rewards for select actions are known to modern players, but only as a peripheral point system: Achievements for Xbox players, or Trophies for Playstation owners. Remix turns these trimmings into the meat itself, where instead of playing the full game and collecting virtual back-slaps along the way, you instead are tasked with completing each achievement, one at a time, one after the other. Such bloodless explanation makes the cycle sound obnoxious, or worse, boring.

There is no fat. There is no lengthy journey across a convoluted map. There is no wasted effort or time.

But in practice it feels more like a lesson in economy; every single thing you do is rewarded immediately. There is no fat. There is no lengthy journey across a convoluted map. There is no wasted effort or time. NES Remix is a game (well, twelve games) reduced into actionable moments. It sideswipes the effects of anticipation, nixing the promise of Then and giving you only a persistent burst of Nows.

As you play you also gain “Bits.” (Is the coin-shape mere coincidence or punning on a certain virtual currency?) Earn enough and unlock Stamps, pre-drawn pixel art of familiar characters from each featured game. These stamps can then be used in the Miiverse, the Nintendo-centric social network accessible through both their handheld and console system (and viewable online), to illustrate a message, giving a voice to players stuck in this anachronistic wormhole of a game. After completing each level, a message pops up from a previous player. One depicts his newfound hatred of Clu Clu Land by surrounding the titular character with bombs from The Legend of Zelda. Another boasts of their high score, shouted by the line judge from Tennis. In effect you’re given a chance to remix these games on your own, crafting impossible tableaux of Ice Climbers mingling with Ganon, or Mario from Wrecking Crew chatting up Mario from Pinball.

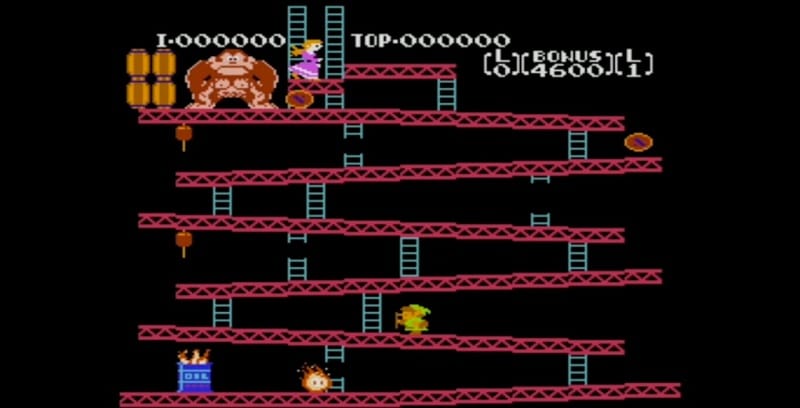

A special “remix” mode offers the same kinds of missions but alters some facet of the game being played. Can you get to the top of the first level in Donkey Kong? Of course. Can you do it with the entire playfield dark but for a spotlight following your every step? Or shown as a mirror image? What if the screen slowly pixelates? Or zooms out? And then: Can you finish the task in as little time as possible?

The compulsion to answer these questions turns an innocent conceit into something more commonly absorbed via intravenous tubing. Each single challenge provokes like a pin-prick: One won’t hurt; but one is never enough, until hours of pricks accumulate into a sizable wound. And I’m not sure this is a good pain.

I’ve lost hours to repeated attempts at meaningless three star scores.

Remember: NES Remix only pretends to be a simple game. Nintendo understand the deadly allure of both nostalgia and perfection: they introduce new players to The Way Things Were; they also challenge long-time players to prove their skills. Make no false move in any given level and be granted three “rainbow stars,” an award for mastery and masochism in equal measure. I’ve lost hours to repeated attempts at meaningless three star scores. What would be a tiny nuisance in a full game here becomes the entire objective. Allocated into such small bits, Remix feels endless, a deep hole down which the stubborn and curious will fall and never reach bottom.

Playing every day, for too long each day, I could not shake the image of the cartoon turkey leg, employed in classic animation as a stand-in for consumption. The villain grabs a juicy drumstick, takes a huge bite, then takes another, each bite displacing the same severed chunk from the whole, the leg never consumed, only a mobius strip of nibbling. You could eat forever this way, never getting nourishment and never getting full.