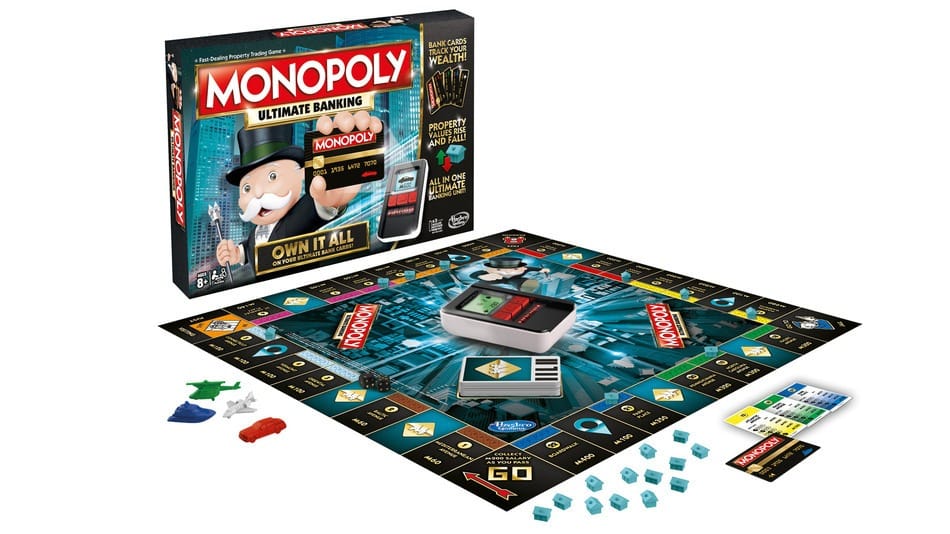

New edition of Monopoly will swap paper money for bank cards

Hasbro has heard your cries for help and taken action. The scourge of adding up payments in Monopoly has been eradicated. Cash is no more.

Monopoly Ultimate Banking Game, which will come out this fall, is set to introduce four bank cards that can be used to make payments and transfer properties. Other editions of Monopoly—of which there are many—will continue to use cash for now, because the future of banking is not for everyone; you have to buy it. (Correction: A 2006 version of the game, aptly named Monopoly Electric Banking Edition, introduced a similar vision of electric payments. Most versions, however, still use paper money. H/T @HalFlow9000)

The card reader is an amusing enough doodad, but what problem does it really solve? Most accounts of this development are light on answers. Maybe this is just change for change’s sake. That would not be unheard of; money, as John Lanchester argues in I.O.U. can best be understood as a force always on the lookout for new opportunities to grow. Financial innovation is therefore something of an inevitability, even if it serves no greater purpose. In that respect, Monopoly Ultimate Banking Game might be an unusually accurate name.

Gizmodo’s “Toyland“ blog, however, offers two possible explanations for this development. First, automated banking might do away with dishonesty (“Is there anything worse in a game of Monopoly than thinking you’ve bankrupted another player only to discover they have a secret stash of cash hidden away?”). What is a capitalism sim without dishonesty, you might well ask, but fair enough. The other issue is that Monopoly is apparently too damn slow. Pesky math! So, those are the problems Monopoly Ultimate Banking Game is meant to solve, maybe.

Monopoly initially served as a reflection of the American economy. The game’s deployment of digital banking, however, moves the game further from how the nation’s payments are processed. America is not a cashless society, nor is its use of credit cards particularly advanced. In 2014, The Guardian’s Heather Long rightly asked “why is the US a decade behind Europe on issuing safer ‘chip and pin’ credit and debit cards?” Scant progress has been made on this front and, as with all economic progress, it is only being experienced at the higher end of the market.

If you want an economy that looks something like Monopoly Ultimate Banking Game’s, it’s necessary to look abroad. “Bills and coins now represent just 2 percent of Sweden’s economy, compared with 7.7 percent in the United States and 10 percent in the euro area,” the New York Times reported last December. “This year, only about 20 percent of all consumer payments in Sweden have been made in cash, compared with an average of 75 percent in the rest of the world, according to Euromonitor International.” For the first time, Monopoly may be more aligned with the future of banking than its past.