NO FUN HOUSE is what happens when a net artist decides to break Unity

If she could, I’m pretty sure net artist and first-time videogame creator Cassie McQuater would throw her body into a shredder over and over again, until she was nothing more than a flesh-colored gloop with a grin. The only setback is her own mortality, but her artwork doesn’t have that excuse, which is why she enjoys recycling it “over and over until the first iteration of the project is basically unrecognizable.”

McQuater is interested in the concept of the “amateur computer user.” It’s what has come to holistically define her work. But trying to maintain this deliberate look of incompetence proves more difficult than you might expect. This is why she finds constantly destroying and rebuilding her projects a necessary and enjoyable past time.

McQuater has us confront the celebrated norms of technology culture.

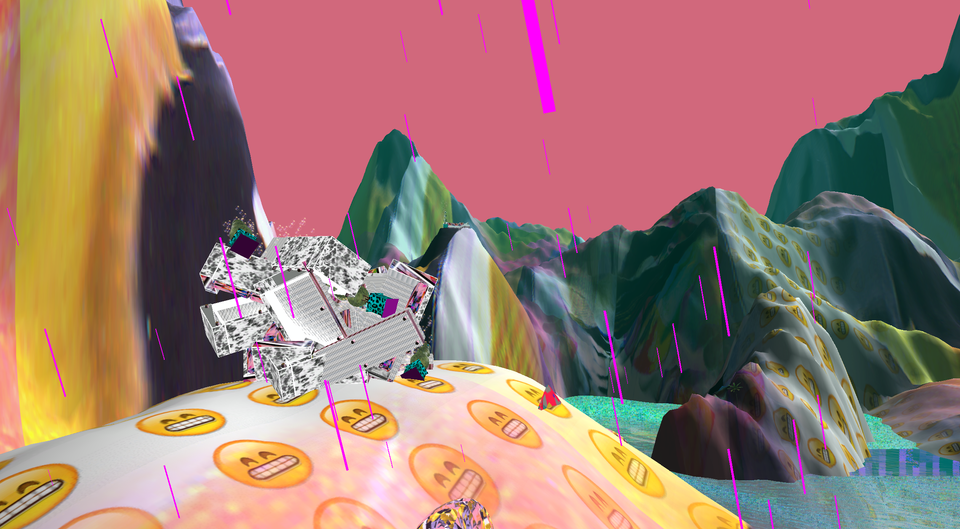

She’s turned the finely detailed cherubs and worshippers of Hieronymous Bosch paintings into monstrously distorted digital collages. Google Earth has suffered a similar fate at McQuater’s hands, its blocky digitizations of real-world landscapes turned into blurry puke-pastel quilts, and polychromatic wireframe oceans. And she used actual amateur 3D models—made by hobbyists and children in Sketchup—for her own collage sculpture project.

Through her lo-fi creations, McQuater has us confront the celebrated norms of technology culture. Why are the most supposedly true-to-life graphics, the latest hardware, and the quickest processes the highest mark of quality? Instead, she celebrates the failures of digital infrastructures that most are so quick to fix—”Unity’s physics engine; the supposed visual failures in the Google Earth application; the ‘miscalculation’ of language by a chatbot; or just a crappy low-bandwidth connection.” She’s also interested in exploring our continually reshaping perceptions of the accepted and professional ways of using software and social media—”how one is ‘supposed’ to interact with machines, computers, each other, what is the socially acceptable way to interact with them.”

This unusual goal for her artwork stems from her own failures. McQuater says she’s a person who fails a lot, and rather than fighting against it, she has instead decided to celebrate this trait of hers (even though she fails at that sometimes, so she reckons). “I like trial and error, and I like not knowing what I’m doing. Probably because when I know what I’m doing I feel like I have to behave a certain way, like there is a correct way to behave and an incorrect way to behave. And sometimes I find that creatively restrictive,” she told me.

aiming low enough so that no one else cares about it

The amateur aesthetic collectively lassos glitches, goofy 3D models, gratuitous emoticons, software malfunctions, garish textures, technological degeneration, and anything lo-fi. Using it is how McQuater escapes the expectations that often come with modern digital creations. It’s aiming low enough so that no one else cares about it other than likeminded others. Although, to say that McQuater is “aiming” for this may imply that it’s more engineered than it actually is. As she told me, McQuater tries to keep herself unaware of what she’s doing, adding that it’s often the case that the idea of anything becoming a project “consciously starts somewhere in the middle of it.”

What she does have is her own set of guidelines to follow: using the most basic software, and most accessible coding, as a way to force herself to focus on and accept her naivety. “I explore the default settings in programs to more fully understand how the programs were originally intended to be used, then I can subvert them from there.”

It’s this that she has brought over to her first videogame NO FUN HOUSE. McQuater was encouraged to try out the medium by the game’s sound designer Ronen Goldstein, after he had watched her dreamlike Google Flyover tours. He helped her realize that what she was really drawn to was the explorative, hands-on aspect of making things, and she wanted the audience to participate in that with her. The interactivity of a videogame was the answer. It’s also a medium that McQuater sees as having a lot of potential right now for her amateur aesthetic.

“I feel like a lot of ‘net art’ has explored the amateur aesthetic heavily, through programs like Photoshop or webcams or Tumblr, but videogames haven’t really had the chance to touch on this aesthetic yet. They are becoming much more accessible now and I’m really excited about all of the ideas that are exploding out of them,” she said.

“NO FUN HOUSE became this domestic, furniture cluttered type of maze”

As to be expected, NO FUN HOUSE is McQuater exploring Unity in its most basic iteration, emphasizing its default settings and “dirty programming”, as she puts it. You explore a domestic house as it would look if being viewed as a reflection in a cracked mirror; tight mazelike corridors hide garish furnishings amid its messy, unfriendly layout. As you slowly creep around in a first-person view, buttons pop up on the screen that ask you to “relax” or “come home,” and when clicked upon they transport you to stretched oceanic landscapes; a picture of paradise if it had its colors inverted and then chewed up by a printer. McQuater revels in the fact that it’s quite possible for players to fall off the edge of the world, or to get stuck in a “weird ocean puddle” forever. “We often equate things like that with failure or bad game design, which are a couple topics I am also interested in exploring,” she said.

The same deviant logic goes into the constant feeling of getting nowhere inside of the game. When you return from these glorious ventures to the middle of corrupted landscapes, you find yourself back at the start of the house-maze, and this happens over and over. There’s more to this than an effort to be irritating, or just plain bad. But its purpose isn’t obvious to the player, as it only makes sense to McQuater’s fragmented mindset at the time of the game’s construction. It’s upon this revelation that we can recognize NO FUN HOUSE as being an abstract reflection of what was going on in her life at the time.

“NO FUN HOUSE was made at a time when I was stuck in a difficult long distance romantic relationship, had quit my day job, and was also existentially confused,” McQuater told me. “I was living in the same apartment my boyfriend and I had shared, but now he was across the country and I was living there alone. His stuff was still there even, but he wasn’t. So, NO FUN HOUSE became this domestic, furniture cluttered type of maze, where the user is perpetually returned to the start as a punishment for taking risks, to reflect on that.”

By approaching videogames through their failures, by using kitschy and “bad” practices, McQuater finds a way to celebrate the prevalence of the amateur in the medium. And it’s not played for comedy as in, say, Goat Simulator and I Am Bread. Instead, McQuater finds a way to express the frazzling troubles and clutter of her mind—almost recreating it in an abstract manner—for which there is no space or time available to explore in the technically prim and proficient world of professional software development. She looks at the frayed edges of digital creation to find a unique form of art that couldn’t exist in any other form.

You can download NO FUN HOUSE for free on itch.io. For more of Cassie McQuater’s work check out her website.