How are the many languages of high fantasy made?

The New York Times has an interesting piece out this week about languages constructed solely for the purpose of fiction. Invented languages have often been proposed to support anything from world peace to feminism, but few have been as successful as those of high fantasy and sci-fi.

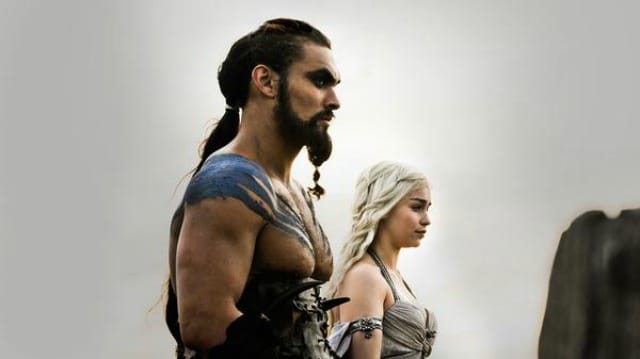

As with any new language, the article argues that crucial to its formation is an acquired sense of community for its practitioners. As the manager of the leading educational website for the Game of Thrones-inspired Dothraki relates, “linguistic diversity is one of the main ways you feel like you’re in a new culture.”

But, according to Arika Okrent, author of “In the Land of Invented Languages,” the success of any of these attempts pale in comparison to those of languages made specifically in service of popular culture of say, high fantasy. “For years people have been trying to engineer better languages and haven’t succeeded as well as the current era of language for entertainment sake alone,” Ms. Okrent said.

With the advent of constructed languages, however, comes heightened expectations of realism and linguistic detail. David J. Peterson, creator of the Dothraki language, explains some of the intricacies of fashioning the new language:

“First you say, should this word exist at all?” Mr. Peterson said. He decided that the Dothraki, with their long braids, or “jahaki,” wouldn’t have a word for toilet, cellphone or even book since that implies they have a printing press. The Dothraki do however have more than 14 words for horse (including “hrazefishi” for a teeny-tiny horse).

Next, Mr. Peterson tried to establish words that would be native and basic (meaning they are not derived from another Dothraki word), toying with letter combinations and sounds he liked. His favorite sound is “JH” as in “genre,” so he made the word for man in Dothraki mahrazh.

“I said to myself, if I won the right to coin the word “man,” it better be cool,” Mr. Peterson said.

After he amassed a small vocabulary, Mr. Peterson tested out basic grammar. He adored the 18 noun classes in Swahili and the negative verb forms in Estonian, both influences in his created languages. He scribbled sample sentences and added suffixes and prefixes to expand the vocabulary.

“The days of aliens spouting gibberish with no grammatical structure,” as Na’vi creator Paul R. Frommer says, are truly over.

–Yannick LeJacq

[via The New York Times]