The Paris Review publishes world’s first game about a memoir about games

Gamelife is a memoir about games by Michael W. Clune. Or rather, it is the story of a life told through games, capturing the formative moments in a boy’s life as he struggles to understand the world, and finds pixels more understandable instead. Having received much critical acclaim for his previous memoir White Out: The Secret Life of Heroin, the critics were poised to love Gamelife. But that doesn’t account for the level of creativity their employing to demonstrate that admiration.

The book, divided into seven separate chapters named after seven different games, not only captures on the relationship Clune develops with these classic 80s computer games, but also their cultural context and relationship to that specific time and place. To recreate this, publications like Slate reviewed the book in a mock text adventure game format. Inspired by Clune’s perspective, which renders computer games important cultural touchstones, these reviewers seem to be wrestling with more than just the Gamelife’s text. Clune has somehow managed to challenge their worldview to a degree, inviting them to see, on an intimate level, how games can help us understand the world.

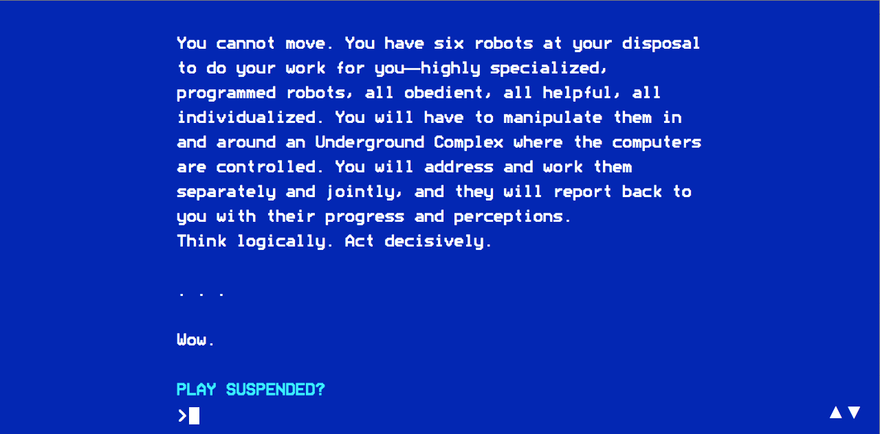

Perhaps most surprisingly, The Paris Review—a publication known for its more traditional content—teamed up with Farrar, Straus and Giroux to create a intractable text adventure review of Gamelife. “We could tell you all about it,” says Dan Piepenbring, “but there are better means of description: as Clune writes, ‘computer games taught me how to imagine something so it lasts, so it feels real.'”

The game itself takes excerpts from the book and allows the player to navigate between young Michael W. Clune’s computer room and living room. His parents room looms above at the top of the stairs, off-limits since they would surely pull him away from his games if they knew what their son was up to. It’s a momentary glimpse into the memoir, which captures its main tension: a boy forbidden from enjoying much of what he loves by well-meaning but ultimately misguided parents. Hints of their eventual divorce can be found in the margins of the scene too, the hushed voices behind closed doors, always fighting.

“computer games taught me how to imagine something so it lasts”

It’s a testament to the power of Clunes writing that these typically traditional print publications are not only embracing the importance of games as cultural objects, but also their ability to teach and communicate. The Paris Review‘s foray into games seems a clear sign of trust—or perhaps more like a leap of faith—in games. Unlike so many other nostalgia-fueled game properties (looking at you, Pixels), Clune does not merely tread through classics in order to pull at the readers heartstrings. He simply tells the story of how games opened up the world up to one boy. And through that simple story, he opens up the reader herself to the same thing.

You can play the review yourself for free on any browser.