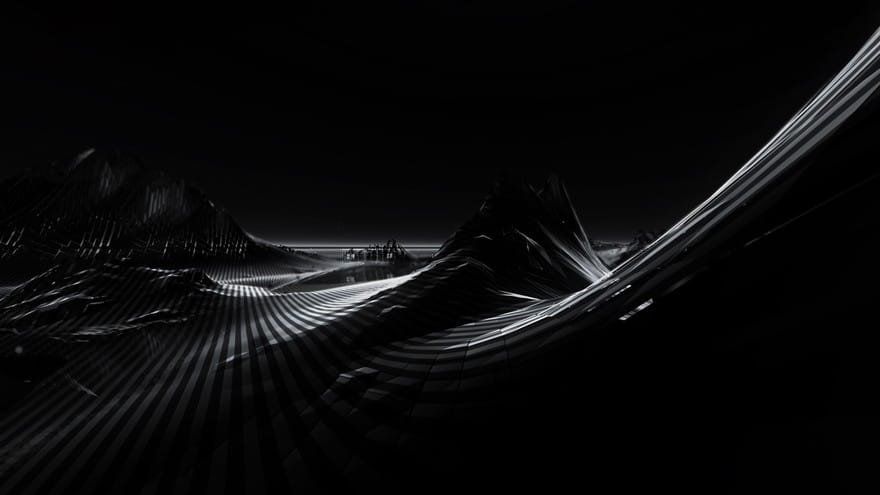

The pitch-black plaguescapes of Orihaus

Header illustration by Jordan Rosenberg

///

When I look at any of Orihaus’s lampblack landscapes, often comprised of slopes or languid inky water overlaid by seemingly non-Euclidian patterns, I feel as though I am staring into a kind of beautifully rendered abyss. Each piece is a careful exploration of some idea he lays out from the beginning. Xaxi is a “mind palace” of sorts concerned with exploring the ways in which we retain and use memory. Hunting Anubis is a rendering of alien planetscape and geometry masquerading as a flight simulator. Cèsure is a long fall down a jagged warm-lit fissure to deep, oneiric landscape.

The chiaroscuro renders are striking, but every game Orihaus designs seems most concerned with place. This love of place (and of the ruminative atmospherics of Myst) is nowhere else as obvious as it is on his upcoming For Each Our Roads of Winter. Spend some time with a few frames from the project and Orihaus’s respect for architecture and shimmering landscape becomes increasingly pronounced. In games, a place can play as great a role as any character or story objective. When I introduced him, we mutually gushed our respect for Ice Pick Lodge’s ghastly plague simulator Pathologic. “For Pathologic, a lot I admired [was] the concept of the city as one body you were tending to as it fought off plague,” he told me via chat. “[Riven, the sequel to Myst] works because essentially it’s a character study. But instead of showing events and interpersonal interactions like most games do, it focuses on the central character in question’s impact on their world and society—through that world.”

Many of these games are in conversation with their forebears. Dirac, his first game, took the basic collection and survival gameplay of Ice Pick Lodge’s The Void and tried to make it a multiplayer experience. “I had a small scope [few art assets, minimalist gameplay + UI] which was a very good move, but since I had no experience in how people would actually react/interact/understand the mechanics, it was doomed,” he wrote. Yet the game is a kind of social experiment he might be interested in revisiting some day, with a larger base of players. “The world would start with enough [energy] for everyone to survive and progress. I wanted to see whether players would naturally fall into equilibrium with each other or snowball into chaos.” Myst and Ice Pick Lodge’s Pathologic are named as distinct influences for Orihaus’s upcoming For Each Our Roads of Winter, and it shows both in the heady atmospherics and the careful, almost fussy attention to detail.

Exploration is revelation. To understand and explore a game is to learn about one’s inner workings as much as it is to learn about the one who designed it. “All art reflects on the artist, but I find it more interesting for my work to provide something that’s more of a shared experience, rather than anything specific to its author’s life,” Orihaus said. That desire for shared experience paved the way for Dirac and made room for the found experience in darkcore light-puzzler Obsolete, which Orihaus released in late 2012 for 7DFPS.

“More guns, more gold, more levels…I don’t think this is appealing.”

“There’s a lot of common vocabulary that most games share and build on, mostly without thinking. I try and sidestep that,” Orihaus said. “When someone sits down to play something, there’s a core motivation that the game is trying to foster. This core motivation can be many things: curiosity, a desire to solve satisfyingly difficult challenges, pure adrenaline, flow. But in many games that motivation is simply to acquire more of something. More guns, more gold, more levels, and I don’t think this is appealing to the better part of human nature.” Orihaus shies away from what Tom Bissell called “gameism,” even if it makes his work less immediately accessible.

Every piece Orihaus creates pulses with heavily atmospheric landscapes and psychodrama. Perhaps it is the monochrome Atelier, cited as a survival/horror/exploration game on his site, that best embodies his aesthetic. The environments are both striking and difficult to make out, much like a night-lit landscape. When asked his particular influences, Orihaus told me, “I think I’m more influenced by entire movements or aesthetics rather than individual groups or works. I see symbolist painting, modern digital art installation art, neofolk music, art-noveau . . . witchhouse, neoclassical architecture.”

There is a sort of “thin-ness” that pervades Orihaus’s work, a liminality: like standing on the cusp of something deep and dark and unknowable. Orihaus himself, in our interview, withheld any personal details. Snatches of his personality emerge in the elements of his design: an occasional geometrical flourish, the impossible mindscape of his terrain. Despite such an obvious exercise of restraint and minimalism in design, the rich darkness of his work exudes decadence. It’s an aesthetic that has been sorely lacking in interactive media to this point; Atelier and Xaxi look like the sort one ought to play with a glass of wine under low lights. Alongside the likes of Aliceffekt and XRA, Orihaus’s impressionistic set pieces of light, sound and atmosphere are a foretaste of some movement that has only begun.