Plug & Play exposes the hopelessness of digital communication

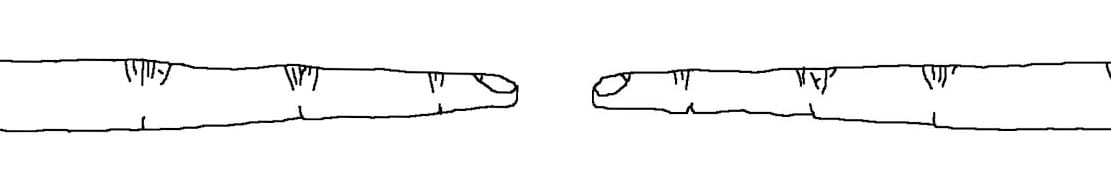

Swiss animator Michael Frei has a strange fascination with fingers. “What I especially like about hands is their expressiveness,” he told Director’s Notes back in 2013. It makes sense: he’s an animator, he uses his hands a lot, to create, to mold, to make actual the visions inside his head. And so do we all, as the hands and their appendages are attributed with our ascendance over all of Earth’s creatures.

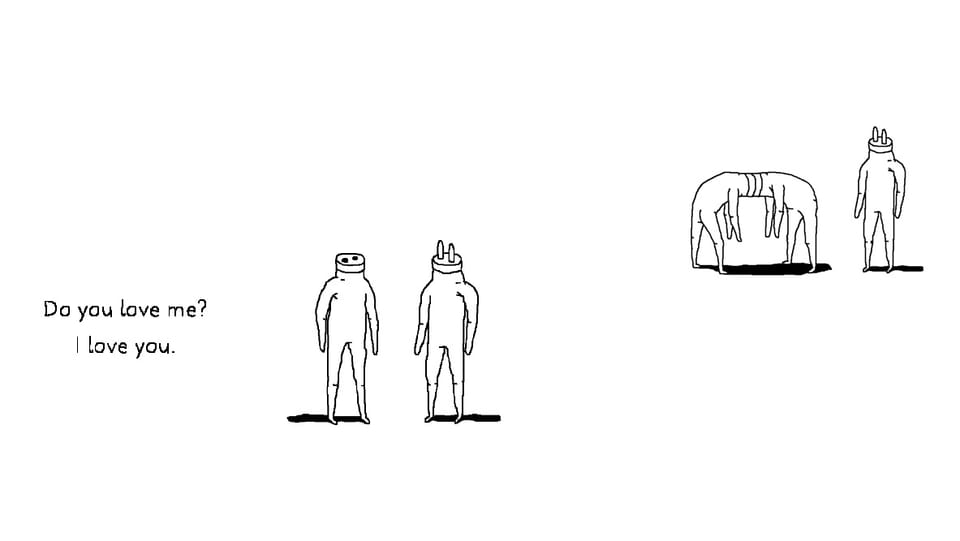

obsessed with fitting in with each other.

With Finger Simulator, Frei had us confront our understanding of what a finger is and how it works; extending their lengths to gross extremities, curling and criss-crossing them like toys. Those same fingers return in Frei’s latest oddity, Plug & Play, right at the start, as if to propose that Finger Simulator was only a compere, an appetizer. They slowly unite from each side of the screen, a soft choir of heavenly voices rising, as if to recall the famous iconography of humanity’s coming-to-be in Michaelangelo’s The Creation of Adam.

But the fusion is clumsy. The fingers miss the collision, so they start over again, and again until you guide them with your own finger to strike. When they do, there’s no godly miracle, no wonder to behold; the nail on the left finger recedes as if a snail into its shell. Whatever was supposed to happen failed. This is the conceit upon which Frei builds his progressive interrogation into the struggles of communicating and connecting in the digital age.

“The word digital originates from the latin word digitus (“a finger or toe”),” Frei also told Director’s Notes. He’s very aware of what metaphor he’s having these fingers play out.

“I love you,” a plug tells a socket it has just met.

It’s a time when we’re increasingly within reach of each other, unbounded by physical distances due to digital technology, yet the overwhelming volume of information and possible number of connections to be made leaves us … where? Through Plug & Play‘s black-and-white binary world of male and female electronics—the plug and the socket—Frei seems to propose that we have become obsessed with fitting in with each other. The tragedy, it is suggested, is that we find it to be a difficult desire to fulfill.

Many of us are raised on the idea that there’s a single person who is right for us. We may spend our whole lives trying to find this one mystical partner. Some of us never do. To this end, we collect friends we’ve made on the internet, some even pride themselves on having more fake friends than others. A step further may be desperately seeking partners on dating sites, judging each other on a selfie or two. The duration required for us to reject one another has been decreased substantially through these digital roulette wheels. And yet the time and effort required to actually connect with one another, to become friends or lovers, has not lessened at all.

Plug & Play‘s most pertinent scene involves a plug and a socket trying to talk through stock sentences with digitized voices, as if computers had been taught how to chat up each other from pithy cue cards. “I love you,” a plug tells a socket it has just met. “I don’t think I love you,” responds the socket. “Are you sure?” replies the plug. An uncertain discussion around the status of this love becomes more abstract until the pair are reduced to trading “yes” and “no,” constantly in disagreement. It lasts until you change the plug’s response to agree with the socket’s, and when you think they’ve finally found an agreement, verging on a chance to connect, the socket changes her mind and walks off.

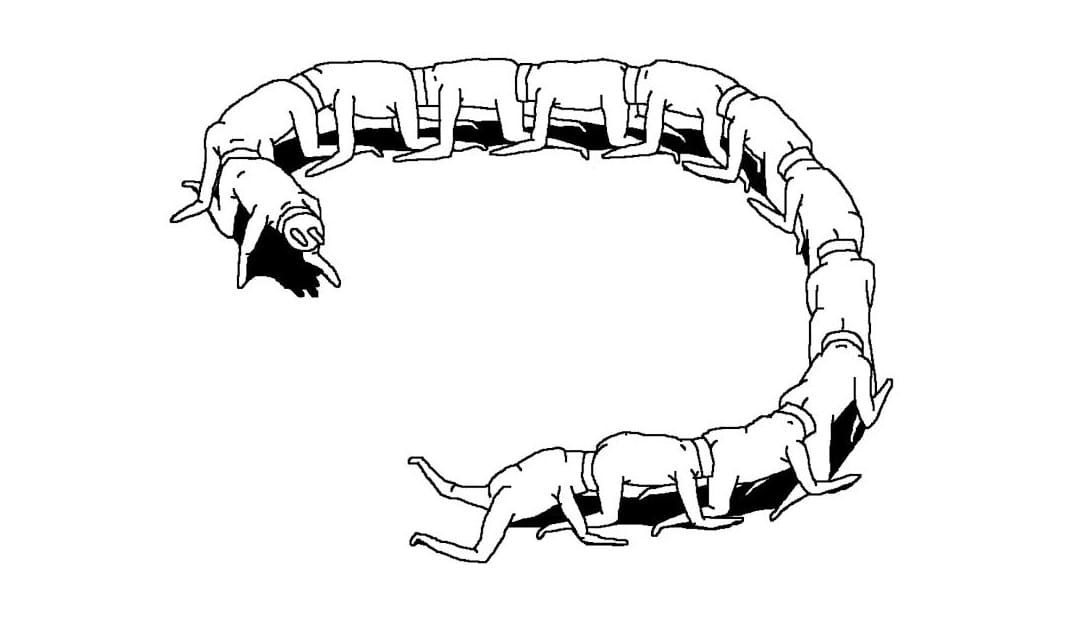

destroyed the distinction between the private and the public.

After this, Frei finds vulgarity in scenes of plugs and sockets connected by ass and head, an Ouroboros resembling the most horrific scenes in The Human Centipede. Those who haven’t found their match take part in orgies in hopes of finding one. Any distinctions between communicating with one and communicating with many have been lost. And those who can’t connect with anyone end up in the dark without the ability to channel the electric current to turn the light back on. It’s strong symbolism and metaphor, but the image that Frei leaves us on in Plug & Play is its most potent.

We return to the fingers, this time the left hand grabs the right’s forefinger, pulling it off unexpectedly, revealing two prongs at its end. This finger is then plugged into a socket on a wall, still pointing outwards. We push the button above the socket, the light goes out, and the finger goes flaccid. Push it again and it erects in the light.

It’s an image that says our world of mass communication has destroyed the distinction between the private and the public. We celebrate celebrity sex tapes, post every intimate moment on Facebook, take selfies anywhere and everywhere just to prove that we’re still available. The complexity of all our emotional and sensual desires appear as desperate as a sexually-charged reflex powered by an on/off switch.

How many meaningful personal relationships have you made recently? Perhaps the digital age’s goal of bringing us closer together has failed. Maybe we’re all analog people struggling to get on in a digital world.