The power and the glory of Samurai Gunn

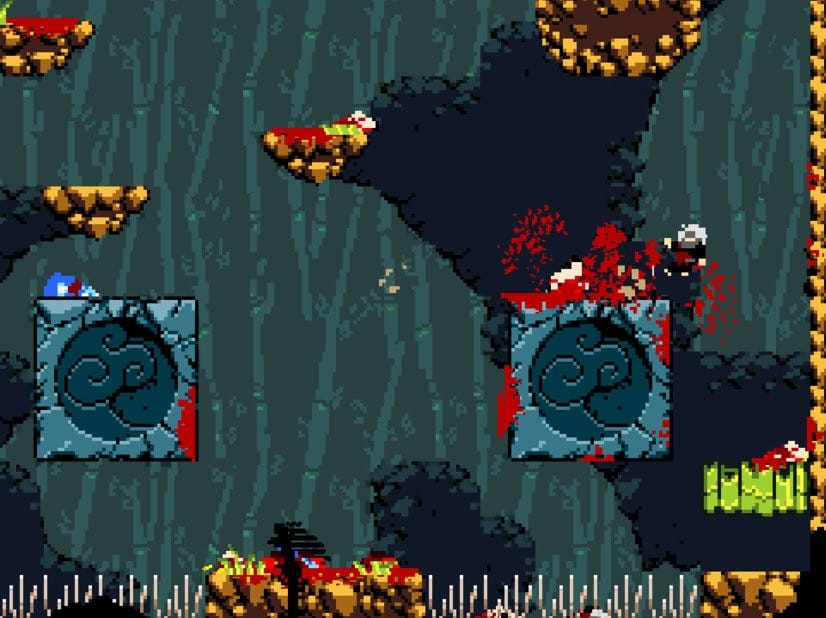

It’s almost the end of the match, palms are sweaty, pulses high. Each player has a stack of skulls in their corner of the screen, one for each kill. Pixelized bullet casings clink across the stone floor, thick red splashes of blood coat every surface. My avatar is a white wolfman, wearing either a green robe with a yellow collar, or a green robe and a radical gold chain, depending on your interpretation. I leap down from a cliff’s edge towards the red-robed samurai below.

Just as we close, my thumbs snap across the controller, and the wolfman makes a short hop; where there was nothing, a white flash of the katana. Time stops, the red samurai splattered into a spray of blood, and the rest of the screen goes black except for a jagged slash parallel with the path of my blade—and in a spotlight of illumination, ragged like a bullet wound, my blue foe dropping down to the floor. Rapidfire, the blue samurai lands, Red’s decapitated head pinwheels through the air spraying a fine red mist, the blue samurai flashes a pistol and a chunky bullet sprints towards me. Already plunging forward, I flash my sword again and reflect the bullet back into his face. The frame freezes again, blue’s corpse already flying backwards. A moment later and he thuds to the ground. I push up on the controller, and the wolfman tilts his head back and opens his jaws.

I am already standing on my chair, head thrown back and howling, “AWWWWOOOOOOOOO!”

* * *

Samurai Gunn is a game of power and glory, and it is not easily finagled into words. This site’s review of Nidhogg, too, struggled with the immediacy of this sort of game; it, too, began where it mattered, with action. I submit that games criticism has a verbal bias. Trapped in words, critics naturally overemphasize games that lend themselves to clever writing but stumble when trying to communicate the supple interactivity that is videogaming’s precious gift. Trudging along in the footsteps of literature and film, we find it easy to parrot phrases about character and narrative. Too often, we shy away from talking about action and find ourselves only slathering adjectives on “gameplay.” We hardly ever capture the sublime grace of flow, when mind and hand act as one and we express our will within the gameworld with utter fluency.

Take pity on us—it’s hard to write with the blunt true eye of Hemingway at the bullfights in Death in the Afternoon or the chatty exuberance of David Sudnow at the dawn of the home console era in Pilgrim in the Microworld. Plus, it’s tough to maintain our objective veneer in the face of the sheer variability of a game-playing experience, especially when we’re busy crafting reviews that none too subtly imply we’re judging the game for Every Gamer On Earth. Maybe your friends aren’t as fun as mine, nor your couch as comfortable. Your eyes might not be as sharp or your hands as fast; maybe you’re a sore loser. Maybe I am all those things and you aren’t.

One hit, one kill, one screen.

But Samurai Gunn, brutal and fair as it is, turns skeptics into players. They don’t even need to touch a controller to be convinced. Samurai Gunn’s design revels in spectatorship, nailing the sport-like elements Bennett Foddy urges for game design. It doesn’t take long to learn. At Rumpus Royale, the indie gaming competition at last year’s Game Developers Conference, Samurai Gunn‘s grand champion, Brendan Wood, had never played before. There aren’t any tricks to learn. It’s just deathmatch distilled to an essence at a solid 40 frames per second. Four directions. Slash, jump, shoot, and you only get three bullets per life. No power-ups, no extraneous pixels, no special moves, no surprises. One hit, one kill, one screen. Having the gun and the sword always ready, with no tell-tale weapon-switching animation, gives just the perfect amount of uncertainty that encourages learning your foe’s play-style and countering their blows before they even happen. It’s what David Sirlin calls yomi—reading the mind of your opponent.

It’s not that the high-stakes, instant kill game is an innovation—consider the first arcade game with a microprocessor, Gunfight (1975); Combat (1976), bundled with the Atari VCS; proto-indie rabbit splatter wonder Jump’n’Bump (1998); and alternate modes like Instagib in Unreal Tournament (1999) and energy sword death-matches in Halo (2001). The fundamentals of Samurai Gunn are already present in its direct ancestor 0space, creator Beau Blyth’s prior local multiplayer game: the gunplay, the katana slashes. But the polish in Samurai Gunn is transcendent. The game is a joy to control, and Blyth’s grasp of “feel” or “juice” is hard to overstate. Max Temkin, the game’s publisher, calls Blyth an “intuitive genius.” Rami Ismail, one half of Dutch indie duo Vlambeer, claims Samurai Gunn accounted for 50% of his most memorable moments of 2013. The juicemeister himself, Jan Willem Nijman, Vlambeer’s other half, said simply, “I’ve never seen heads or shells bounce that nicely before.” Where 0space is a thinking man’s deathmatch that emphasizes survival over slaughter, Samurai Gunn pairs its rapid pace with aesthetic emphasis by pausing for a fraction of a second for each kill during its iconic slash-frame.

Samurai Gunn is a game about the decisive moment. Henri Cartier-Bresson, the legendary French photojournalist who passed away a decade ago, released a collection of stunning prints under that very title. For Cartier-Bresson, every subject had an intuitive instant where it could create the most powerful image. The challenge of photography was finding just that moment. Samurai Gunn is strikingly similar—you judge your moment, you wait for just the right fraction of a second, you press the button: instead of a shutter snapping, there’s the white flash of your blade, and a static image is created, not of a photograph but of a frozen frame at the moment of triumph, a portrait of your foe at the millisecond of dismemberment. But if you press the button too soon, or your eye wavers, the sword flashes but nothing is captured and you stand flat-footed, inviting defeat. Nothing heightens the power of the decisive moment like the showdowns triggered at the end of a closely contested match—the winner and closest nemesis have a one-kill rematch on the top of a mountain lined with spikes, silhouetted by a beautiful sunset, or in the midst of a castle siege. The clarity of this visual design is only besmirched by the lack of color contrast between character sprites and the backdrop—on snowy levels, the white wolf’s head blends in completely.

Beau Blyth managed to tap into some kind of teenager collective unconscious about the inherent awesomeness of samurai, channeling the epic power of legendary samurai like Miyamoto Musashi, the unflappable cool of a Kurasowa film, and the goofy kinetics of the grindhouse flicks that get sampled by the Wu-Tang Clan. He incorporates that sense of cool into the juicy katana controls—your sword never glances clumsily off a wall like in other games, and it doesn’t bob around awkwardly while your avatar flits from wall to wall and leaps twenty times its own height. The slashes are always frictionless, cleanly separating your opponents into deli slices. In Samurai Gunn, the instant, weightless, fatal grace of the katana makes it feel like anything is possible. No matter how far ahead your opponents, it always feels like if you are just a little faster, bolder and more focused you can dominate your opponents and snatch victory from the jaws of defeat.

Videogame reviews that fail at their description of the sublime often regress into a sort of buyer’s guide. They tell you, in short, how far out of your way you should go for the game. But Samurai Gunn inspires just such a decree. If you don’t have four controllers, a couch, and three friends yet, Samurai Gunn is a compelling case for making the investment.