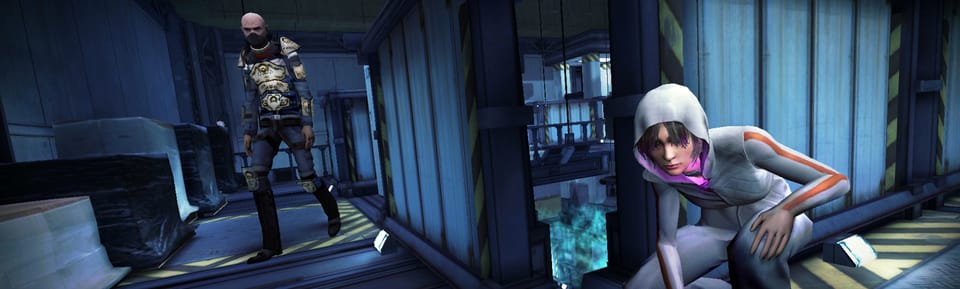

Republique shows that tablets can tell emotional, realistic stories

Emotions don’t flow naturally from game characters like Hope, the hoodie-wearing avatar and lead digital actor in Camouflaj’s Republique. It takes a number of people—a voice actor, a writer, an actor in a motion capture suit, a team of animators—fusing together various aspects of their likenesses, personalities, and talents to create the illusion that Hope is a person and not just some automaton escaping from the game’s Orwellian future.

But it also takes emotive facial technology. If you peeled back Hope’s face to see the code underneath, you would find something like neural connections, little switches that grant animators control of her countenance: one for moving the corners of her mouth, another for her jaw, one or two for her brow, and four more so that her eyes can blink and rotate and twitch as the flesh stretches across her cheeks.

It’s not about embalming a corpse but breathing life into a soulless, inanimate object

“You’re going to stare at her eyes because that’s what we do when someone is speaking, but you will notice her face right away if something doesn’t look right,” says Kaitlin Spangler, the lead animator who is responsible for making sure everything about Hope congeals. Among other things, this involves taking footage of the voice actress Rena Strober’s facial expressions as she records the script, then using a computer to massage her features to fit the heroine’s longer face—for instance, changing the shape of her lips when she smiles, or pronounces a long “O” sound. “When everything is working together and feels organic and natural, that’s when you begin to lose yourself in the performance,” Spangler tells me.

The French film critic Andre Bazin once wrote that most art is motivated by a mummy complex, a psychological drive of the species to cheat death by preserving itself in things like paintings and hieroglyphs. But with Hope and other persuasive 3D animated characters, this seems backwards. It’s not about embalming a corpse but breathing life into a soulless, inanimate object. “She really comes to life when we get to the point where the eyes and the mouth and the brows are all working together: that moment when everything feels in unison, and her cheeks are moving with her mouth and her eyes are dancing quickly and blinking fast,” Spangler says. “When you hit those moments, its like, ‘Wow, she really looks alive!’”

Republique was designed with tablets in mind, so it’s a major coup how Hope shows up many of the highly detailed but utterly deadpan mannequins that populate games that comes out for computers and consoles. In digital animation, a little individuality goes a long long way. It’s not so much that the studio sees their star as a polygon model to be chiseled out the way a sculptor does a slab of granite. Instead, they think of her as the chisel itself, a craftsman’s tool to inhabit and press themselves through.

“I look at myself as more of an actor,” she continues, explaining how it’s super important for an animator to know how to theatrically emote. “Being goofy, being able to put yourself in the character’s shoes, [and imagining] how she would act in that moment” are just as crucial as being able to manipulate a pair of eyebrows and signal a feeling of anxiety. She tells me the knitting of eyebrows is a gesture Hope has been doing a lot of through the first two episodes, but as the character grows in confidence over time the shape of her eyes will adapt. It takes more than moving joints and ligaments to convey that.