Retro Game Crunch proves that "retro" is more than a look

Retro Game Crunch used nostalgia as a selling point, and it worked on me. It’s a seven-game compilation born out of a game jam; like the Oulipian writers of bygone Paris, the jammers behind this and thousands of others see limitations on time and hardware as not only a challenge but a funnel for creativity. The term “game jam” carries a whiff of ephemerality, games created in moments and worth playing for about half that time. A resource for brainstorming, but merely a start. Retro Game Crunch argues that a brief experience need not be shallow, and can instead be quite affecting.

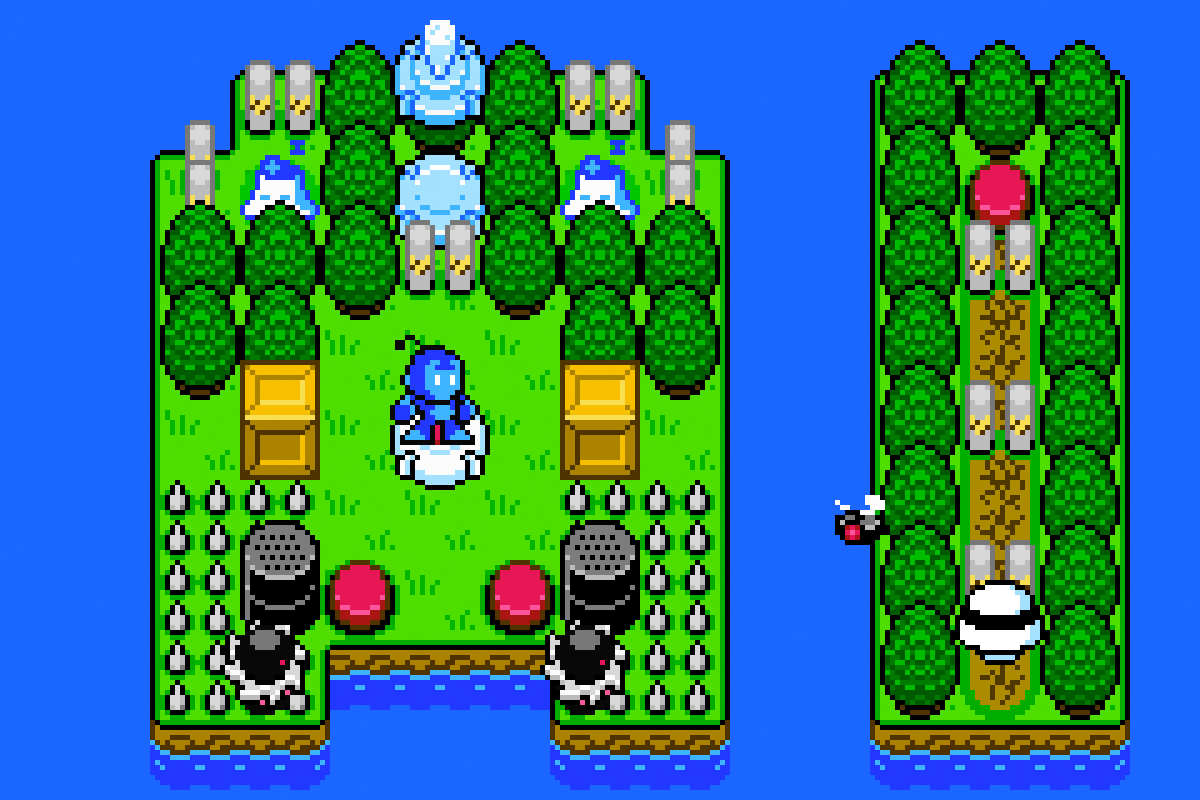

I’m putting a lot of pressure on Retro Game Crunch in this respect, and while, as with any game, I can’t expect that you’ll see it through the same lenses that I do, I think many would find each of these titles felt particularly familiar. In large part this is because these games feel almost passed down, like a fourth-generation cobbler fixing shoes with passed-down tools and familial knowledge. Super Clew Land tugs on our Kirby strings; End of Line gives the blue bomber a puzzle-based death wish; GAIAttack! is a vertical beat-em-up, Paradox Lost arms Samus with a time-travel gun; Wub-Wub Wescue could be found tucked in the corner of an old Pizza Hut; Brains & Hearts is a deceptively simple two-player puzzler; and Shuten wears its influences in the name.

All these games drip that retro A/V aesthetic blowing up tumblr with 16-bit demake gifs, but more importantly they also nail that retro feeling in execution. Each one elegantly cites its source material, but pushes further and twists them up in intriguing, playable, and fun ways. Retro Game Crunch could serve as merely a creative dissertation on my personal NES past, almost directly referencing the singular genres and titles of the era and plucking my heart strings accordingly. This reverence for what came before, and willingness to incrementally grow beyond, shines through Super Clew Land in particular.

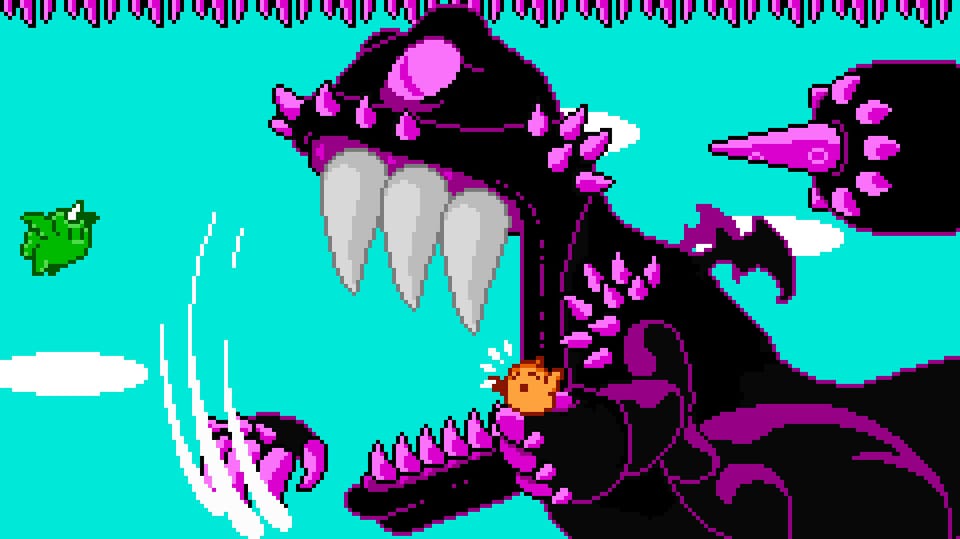

This shouldn’t be surprising, as it was the jam that inspired them all. The itch Clew scratches can be traced back to the look and feel of that old voracious pink sphere, Kirby. The difference, though, is Clew expands on the idea of digesting what you inhale, rather than gaining its power immediately. You hop around, eating the only things that can’t kill you, and what goes into your stomach has to be arranged by colored protein in specific ways. This allows you to evolve legs, a fin, and more. But the body doesn’t stop just because the stomach’s working; you arrange what you’ve eaten on the face buttons while still dodging claw swipes and spiked fish with the d-pad.

failure comes not from death but from accepting the inevitability of death.

Eventually you fully evolve, and the mini puzzle game of stomach management disappears and you focus solely on your multitudinous methods of travel to peek into every corner of the world. There’s a fair bit to explore, with spikes and environmental hazards providing the dextrous challenges. It’s the kind of game that, as in the days of yore, shows you where to get the next objective, then how, but your thumbs just can’t keep up against the spikes, at first. You’re so close each time that the next one is it, just one more time, until like a zen archer who looses an arrow while blindfolded, the path becomes clear in an out-of-body way. This is what is meant by comparing Dark Souls to early NES games, where failure comes not from death but from accepting the inevitability of death. Each return to your last save point is a chance to learn, even a minuscule amount, until it’s enough to transgress all the challenges of the game.

That said, it’s not particularly long, in that way that old NES games were never large but demanded a cyclical karmic confrontation. But if you have the muscle memory from days of old, then you’ll pick up on the moves pretty quickly. I took down the final/only boss after about an hour, but at the same time, felt satisfied that this game accomplished everything it set out to do.

And really, that’s what Retro Game Crunch nails for the most part: the style, the flash of a boss’s weak point, chunky pixels and limited (if still vibrant) colors, the surgical strike of finely honed gameplay that gets in and gets out with only the necessary fuss. Most of the games with endings can be reached within 1-2 hours. On one hand, this hews close to those titles of the era, running short on content but long on replayability in the face of tiny bugs that were more often charming than game-breaking. Or it could be nearly three decades of instinct on my part.

Even then, throughout all of these games I was practically cross-legged on the floor playing to the end, thinking of my dad, biting my lip through the trickiest puzzles, cheering for Clew and Abbie and Wub Wub. Crunch emulates Retro Game Challenge in many of the ways that Challenge itself capitalized on wistful NES daydreams, though that DS cult “hit” had the benefit of a larger team and longer turnaround time. The small three-person crew responsible for almost all of Crunch’s titles put in a knowledgeable effort and bore seven gems that do more than simply service the past—they expand on it. It’s a collection fueled by nostalgia but not defined by it, finding captivating creativity in the limitations of hardware and the long tail of human memory.