The secret to social game success: sound

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel.

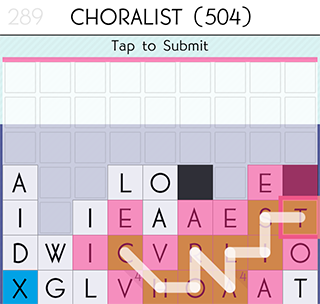

Scrambled letters crowd your screen. You swipe your finger over a familiar combination: M-A-G-N-E-T. Each subsequent letter sounds a crisp “tick.” When the word registers, a high-pitched “ding” signals the find. Then you notice something; you touch the adjacent I-C, and finally release your finger. Letters forming MAGNETIC disappear one by one as an ascending arpeggio rings out. The remaining letter tiles fall into place like Tetris blocks, each clattering down with tiny thuds. These are the sounds of Zach Gage’s SpellTower.

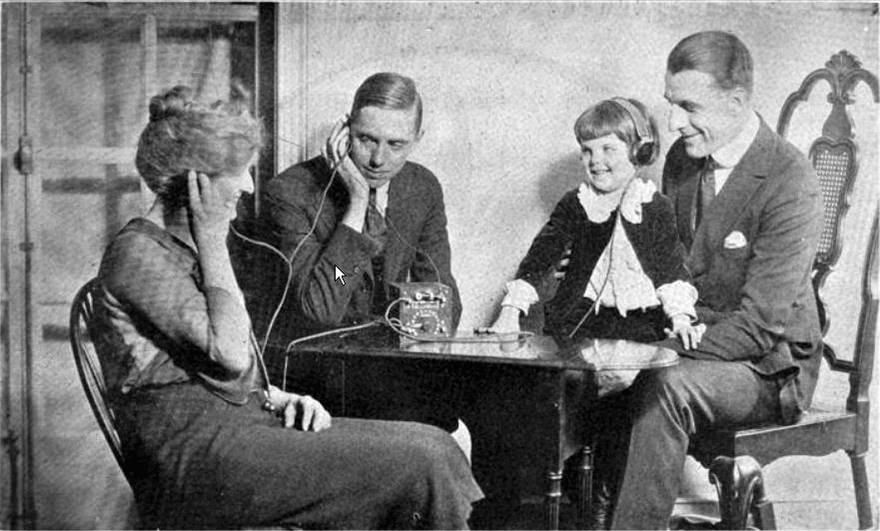

Social games are successful only if played over a long period of time. They need to proliferate through a circle of friends, or online strangers, over many repeated playings of the same game. Music inevitably loops, sound effects clang and clang again. Worst-case scenario: You mute the sound and play silently. But the audio design of a well-made game enhances the whole; what might be off-putting becomes integral to the experience.

The audio design of a well-made game enhances the whole

Dr. Karen Collins studies the relationship between interactivity and sound as an Associate Professor at University of Waterloo. Her first book, Game Sound, came out in 2008, the same year the App Store opened and changed the mobile gaming landscape. The explosion in releases has given her much fodder to consider; unfortunately, too many players never hear the focus of her research.

“It’s unfortunate that many social games have their sound turned off right away,” Collins wrote me in an email, citing the addictive quality of these games, and the places we play them even when we shouldn’t be, as necessitating a lack of volume. “People are playing at work, and on the go, [and] even when played at home, a lot of players turn the sound off.” According to Collins, they’re not experiencing the whole game.

Playing on mute “is like asking someone to judge a movie with the sound off. The sound and image go together and experiencing one without the other leaves only half an experience.” I think back to SpellTower; without its distinctive pings and accumulating notes, I doubt Apple would have chosen it as a pre-loaded game for each display device in their nationwide stores. Nor would Gage have been featured in WIRED, Forbes, and the New York Times Magazine. A silent SpellTower is fancy digital Boggle. The best videogames involve multiple senses, plucking connective nerves until what we see, feel, and hear are all one. And the right sound effect can leave you satisfied—or wanting more.

Collins co-authored a study on the psychological effects of sound on gambling, and admits there’s some overlap in how game developers use sound. “With mobile games, there is less deception—they’re not duping you into thinking you’re winning when you’re not,” she writes. But even a half-note change in pitch can seriously affect the player, whether they stand over a slot-machine or tap on a tablet’s screen.

“In both games and slots [there] is a kind of build-up that happens when you’re about to do something,” Collins explains. “For instance: you might get four objects in a row and each sound is a step up. But the fourth note is a semitone … it leaves you really unsatisfied. So you get this ‘near miss’ effect, where you nearly accomplished something, but not quite.” She compares it to stopping a sentence before saying the last word. Even if we understand the meaning, we need a sense of finality. “Games play off that frustration,” Collins writes. “You want to hear it resolve, so you play again.”

Each two-dot line I connect feels woeful, a two-note lead up to some unheard song

I play another social success story, the elegantly simple Dots by Betaworks One, with Collins’ notes in mind. At its core this is the same game you played in grade school, connecting lines and squares out of pencil-and-paper grids made from the eponymous punctuation. I’ve played it on countless subway trips, hearing only the screech of brakes or the chewing of that guy who takes his breakfast on the train. Now I turn up the volume and listen.

Each two-dot line I connect feels woeful, a two-note lead up to some unheard song. Three dots in a row feels slightly better, but something is amiss; I notice these are not Julie Andrew’s do-re-mi of the pentatonic scale but some other unresolved variation. Only when I finally connect four in a row, creating a square, does the game produce a full chord and resolve my aural angst. My phone buzzes: a tiny victory. The playfield awaits my next move. I put in my headphones and try again.