To Shooter, With Guilt sifts through the rubble of digital warfare

It was in the original Modern Warfare when Ansh Patel first felt guilty about a shooter. He was playing that ice-cold AC-130 gunship scene, looking down on a taupe-hued countryside, the crosshairs hovering over the steeple of a church housing rebels. Nail those guys, a voice crackled from the television.

“They’re just these dots. When you kill them, it’s just a couple of dots disappearing from the radar,” he recalls, but it caused him some degree of pain. Probably not much in the grand scheme of things—just that little pang of discomfort, like he was a horrible person for liking this game, that is familiar to anyone who’s digested a recent Call of Duty campaign. “It’s the absence of guilt in the scenario that actually made me feel guilty,” Ansh tells me.

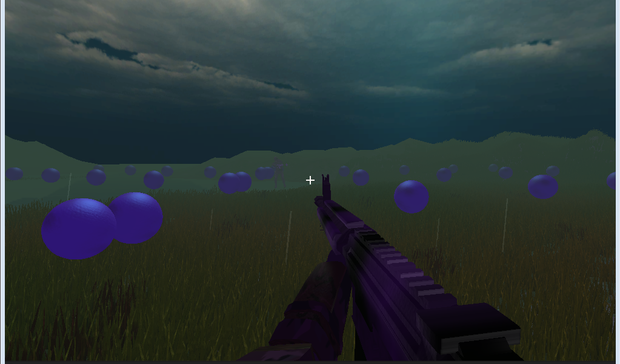

This was the catalyst for To Shooter, With Guilt, the anti-shooter shooter he constructed for the 2013 Seven Day FPS challenge. The game is appropriately surreal, as is the strange realization that a fun video game can upset your moral equilibrium. Yet this is something conscientious shooter fans have learned to drown out, because the level of violence and moral consequence are often at odds. As Ansh points out, it’s easy to be disillusioned by the state of the modern FPS. The statement he’s making in To Shooter, With Guilt is that shooters are ethically okay if and only if they have adequate guilt built in.

I once jokingly referred to him as the young Salman Rushdie of games.

Ansh is your typical millennial. He is socially aware, an active blogger, a creative writer, and an ambitious student at university. During the interview, I once jokingly referred to him as the young Salman Rushdie of games. Ansh lives in Mumbai, mentioning how the economy there has been westernized over the past two decades. That includes an influx of Western culture, such as violent shooters.

His first proper game, To Shooter, With Guilt, is a bit of a ruse, in that it can’t be won. Initially, it resembles any other shooter, but the rhetoric is readily apparent. “You’re in this inescapable dance…. The more you kill, the more difficult it gets,” he says. When you shoot enemies, instead of dropping to the marsh, they transmogrify, twisting into corpses, and they gather in a mob. Further attempts to disperse them are met with your bullets being reflected back at you. “When you step onto the battlefield, wearing that gun, enemies stop being human. They are raving animals,” a voiceover commands, but it sounds suspiciously like Ansh speaking into his hand. A tad operatic, but not bad.

Introspection is the only way for the genre to evolve.

The concept was rushed, Ansh admits, assembled in the haphazard fashion that game jam projects are. “It comes across as a half-baked idea,” he says. He realized halfway through the jam that he didn’t have the time nor the resources to actually convince the player to give up their run-and-gun pastime, as he himself has—for the most part. “If I cannot make them feel guilty, then why not put the character and the player in conflict? The soldier feels guilty because he’s the one doing the killing. The player is just in it for the ride. Five minutes, have a bit of fun. He doesn’t really care. He’s killing soldiers. Let’s create some conflict,” he says.

He wants to wonder, “Why is the developer asking me to look at this bloody portrait?” He thinks that we deserve an answer.

This is a smart move, and one high-minded shooters like Far Cry 3 should take note of. At times, Far Cry can come off as condescending, inviting players to leave the screen door open, and then lecturing them for letting in flies. But Ansh is content to have it both ways. “Shooters need to explore the space between the player and the character. That’s an interesting thing about shooters. You’re someone, and the character is someone else,” he tells me. In that sense, apathy isn’t all that important. You can have your bro-time, while your character does his best Charlie Sheen. There’s no need to cross signals, as in Far Cry.

Ansh points to Spec Ops: The Line as an example of a game that gets it right. “Your character is going insane and probably hallucinating, but you press on because the game told you to go along with that,” he says. He likens that game to High Noon, the nonviolent Western that was a reaction against the status quo, saying that introspection is the only way for the genre to evolve. Other comparisons to film are hit and miss. His statement differs from that of anti-war films, such as those by Godard, in that he’s not protesting actual war. But it’s the same in that it’s a reaction against the way war is presented and glorified.

The whole thing raises the issue: does virtual violence desensitize the youth of the world to the reality of war? He doesn’t seem convinced that it does. Rather, he just wants to see more thoughtful portrayals. He wants to wonder, “Why is the developer asking me to look at this bloody portrait?” He thinks that we deserve an answer.