A good mashup is an invigorating thing. By combining two divergent works or genres, a mashup can illuminate and play with the tensions between their various assumptions and expectations. These juxtapositions can bring new shading and texture to the otherwise familiar, or provide opportunities for characters and stories that couldn’t exist in either of the source genres on their own. Rian Johnson’s Brick, for example, combines gumshoe noir with high school drama not just as an exercise in style but to communicate the social stratification and indifferent hostility of figures of authority that so often characterize adolescence, as well the arbitrary nature of the affectations we use to define ourselves in those fraught transitional years. At its best, a mashup can be more than simply a question of external trappings, but an opportunity for something new, informed but not constrained by the grand collection of what came before.

As an exercise in form and atmosphere, White Night is a wildly successful survival horror/detective noir hybrid. Armed only with a box of matches and the narrator/player’s hardboiled sensibility, White Night tells a slowly darkening story of curiosity, obsession, and the history of violence hidden within a family and the pitch black hallways of a mansion from which not even death can offer escape.

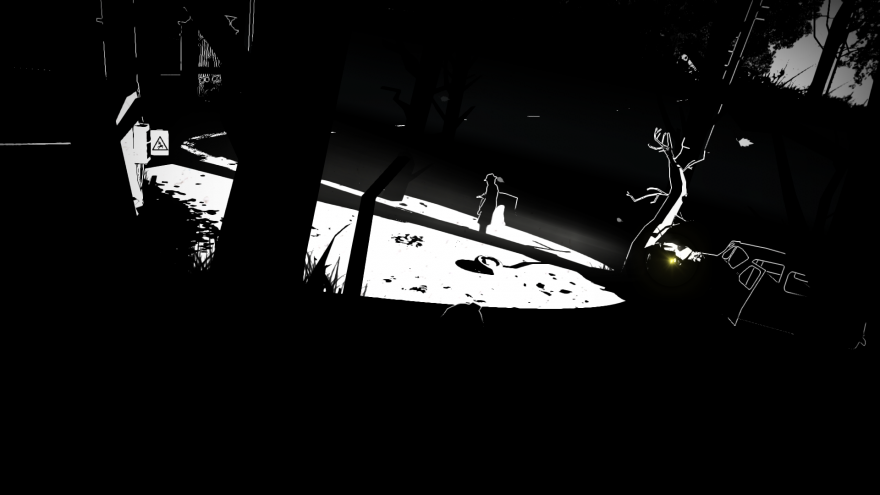

By draping its world in absolute contrast—black and white like few noir cinematographers even dreamed, dark not just to the exclusion of color, but almost even beyond the possibility of gray—White Night becomes in play a game about light. Match by match, the player doesn’t just illuminate the world, but calls it back into being to preserve a few minutes longer the possibility of a tentative, shared existence. Darkness is not just an obstacle to exploration, but an active, lurking danger of its own.

Should the narrator run out of matches, or simply stand in the darkness too long, it will swallow him whole, with the same, brief floating text of suffocation and madness that appears when the player is caught by one of the flailing phantoms who stalk the mansion’s halls.

As the narrator unlocks new rooms, on the other hand, light becomes not just a tool but an ally. Illuminating objects creates the ability to interact with them, so lighting a candle can create a save point, and starting a log in the fireplace can free up the narrator’s hands to pry open an otherwise invisible and inaccessible trunk.

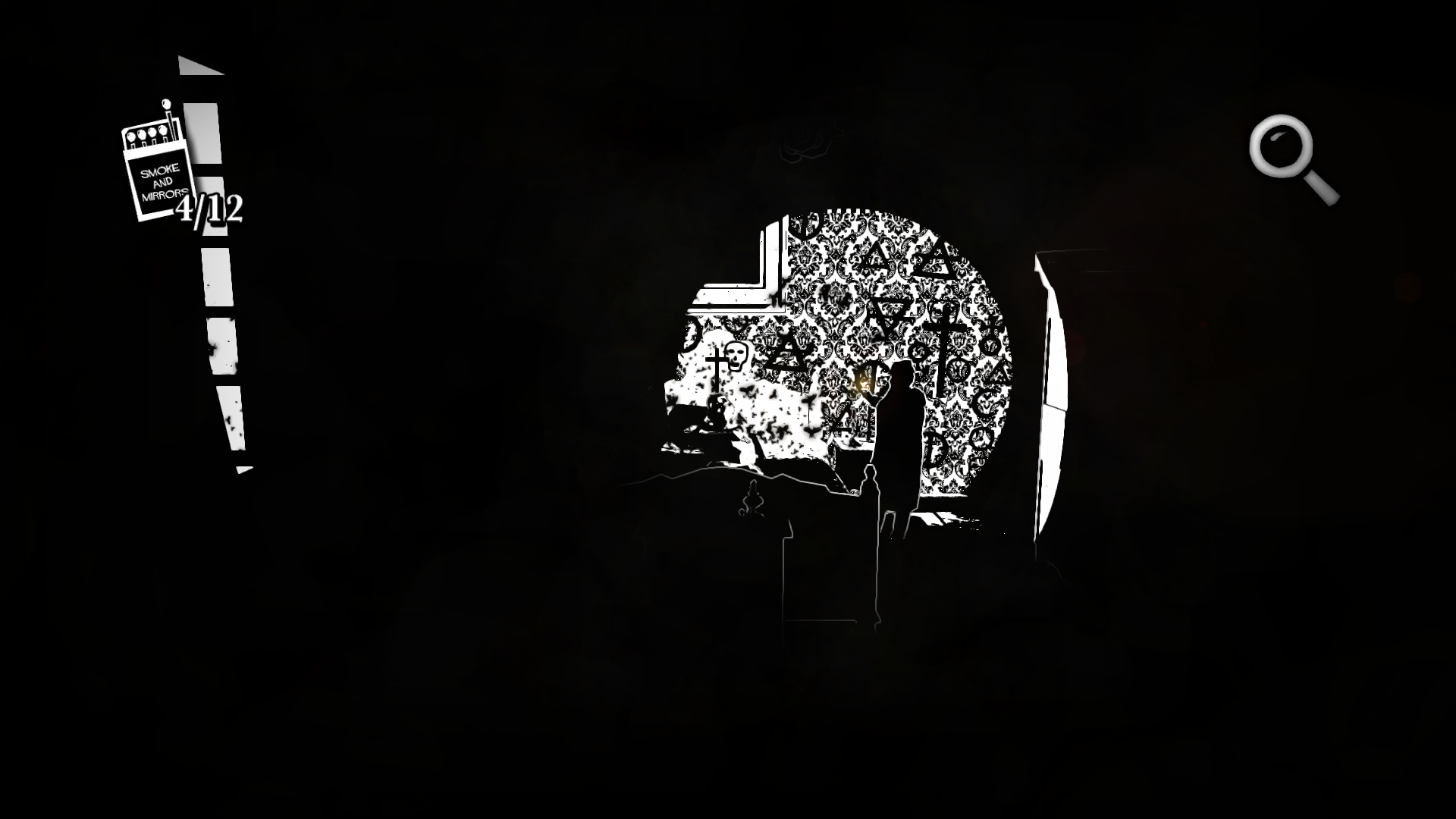

Supernatural detective stories have become something of a subgenre of their own in videogames—Indigo Prophecy, The Vanishing of Ethan Carter, Murdered: Soul Suspect—but White Night distinguishes itself by getting the feel of noir right. It’s there in the 1930’s setting and the sultry jazz soundtrack, but also, surprisingly in the survival horror-inspired unpredictable camera, which serves in context as a series of jump cuts, especially when the player is trying to move quickly from room to room.

And it’s there in the way that crime and violence lurk under every veneer.

White Night is a game driven by violence between women and men. A man enters a house marked by signs of terrible and repeated violence against women and is pursued by the shades of a woman who despised and was despised by her husband and son. There are drawings and photographs of women’s bodies throughout the house, more grotesque and mutilated as the player explores deeper recesses.

Once, in order to advance, the player has to stab two of these pictures with knives.

And this is where the game’s particular noir mashup loses something from the original:

The figure of the femme fatale is not unambiguously subversive. While the femme fatale seeks to escape gender (and class) proscriptions by entering the (male) world of crime and violence, the presentation of such characters normally participates in and reinforces the tropes of unchaste women as sexually predatory and women more generally as less than entirely trustworthy. The activity of the femme fatale is an attempt to assert agency in a society where such assertions (in fiction and elsewhere) face strict limitations. Like most characters who seek to escape social strictures, the femme fatale is normally punished severely in the end, dying violently or facing the brunt of the force of the law.

But the driving motivation of the femme fatale is to seize control of her own life using the tools at her disposal, whatever cost that may entail. It may be proto-feminism rather than feminism, but it’s powerful dramaturgy.

White Night fills the space normally occupied by the femme fatale with Selena, the luminescent specter of a jazz singer whose figure both attracts and protects the player character. As his mental state is more and more influenced by the letters and diaries he discovers, the haunted man talks of saving Selena, of bringing her back, but the corpses of William’s mother and father, hastily exhumed and placed rotting in their bed provide a grim picture of what sort of recovery is possible for the dead.

By making Selena a ghost, and revealing her background in optional collectible letters, White Night makes questions about her agency a matter of the past rather than an active component of either the story or the play experience. She is a figure of obsession, in control of nothing, not even existing except in the view of the man who killed her and animated only to the extent to which the narrator comes to share that view of her.

All of which could be fascinating if White Night embraced and examined its own shadows just a little more. For a story that drives its narrator to identify with the viewpoint of a man revealed increasingly to have been driven by an unhinged obsession and violence, White Night attempts to end in a strange gesture towards absolution.

Which is to say that as promising as that mashup may be, White Night is unable to keep the elements from separating. In noir, after all, the available resolution is malaise. Justice is not available, but most of the worst offenders are punished, more or less, and life goes on. The gumshoe, if there is one, cannot restore the fallen world, but life carries on, mostly unaffected beyond the immediate participants. There is room for a man to have done his best, stained, but not implicated.

In horror, we confront monsters, and survival is the only operational term. The resolving state is trauma rather than malaise. Forgiveness is a non sequitur. For a game whose design dwells so deeply and strikingly in darkness, it is unhappily ironic that the story prefers at the end to turn toward an illusory light.