The tortured, hateful parentage of South Park: The Stick of Truth

I’ve seen every episode of South Park. It’s hard not to. The controversial cornerstone of the cartoon canon was widely available long before Netflix and Hulu became household staples. You generally know what you’re getting with South Park: bawdy social commentary that’s as smart as it is cringeworthy. Every season episodes vary as much as you’d expect from a show consistently written in a single day. South Park is always either great or terrible; you can never divorce it from the signature immaturity or the constant flux in quality. Do you love it or hate it? Both, probably. South Park’s relationship with videogames is a lot like the show’s relationship with everything else, and our relationship with South Park itself: love/hate.

Trey Parker and Matt Stone are as present in the show’s 16th season as they were in the beginning. Like many talented comedy writers, the pair has a knack for highlighting subtle truths. It takes a great deal of skill to do what they do well, and by this I don’t mean the poop jokes. Newscycle-fueled plots vary from week to week, but most episodes begin with a premise Parker and Stone have perfected writing. South Park is built on their accurate depictions of how it feels to be a kid, in particular, the false sense of monumental importance children infuse into their play. The lives of the Stan, Kyle, Cartman and Kenny are as globally important as kids like to imagine, with their games always ending up in the center of real-life adult drama.

South Park’s infamous episode “Make Love Not Warcraft” is one of the first times the boys’ games went digital. Instead of roleplaying as usual, the boys try to play WoW but keep getting killed by a higher-level player who kills other players for fun. This player is the nerd personified: a fat mouthbreather stewing in his own filth. Word gets to Blizzard that he’s killing everyone, and the situation turns catastrophic, because it has to: it’s South Park. To save the day, the boys must defeat this uber-nerd, but first they need to level up. They do this by walking through sparsely inhabited areas of the game, killing boars.

Kyle: Dude! Boars are only worth two experience points apiece. Do you know how many we would have to kill to get up 30 levels?

Eric Cartman: [pulls out a piece of paper] Yes. 65,340,285, which should take us 7 weeks, 5 days, 13 hours and 20 minutes, giving ourselves 3 hours a night to sleep.

If the kids want to play the game, they have to kill millions of boars and level-up. But wait, aren’t they already playing the game? A montage follows, where the boys spend so much time playing they devolve into a state of nerddom mirroring their nemesis. The outside world carries on as it always does while they sink into their chairs, shoving down processed snacks and duly communicating orders between labored breathing. Their faces hardly register emotion as they stare into the screen, hypnotized by the rhythm of their one hit kills. Boar after boar after boar. Their experience level rises, but they experience nothing beyond numb, narcotic clicks of the mouse.

After “Make Love Not Warcraft,”’s success, Parker and Stone tackled another videogame phenomenon: Guitar Hero. This episode parodies the trope of the rockstar-rise-and-fall. Stan and Kyle get amazing at Guitar Hero and become as famous as the game suggests the player will become. In typical South Park fashion, the story ratchets up the absurdity to point out the subject’s pointlessness. Like in “Make Love Not Warcraft,” they are hardly registering the movement of their fingers while they re-play iconic rock n’ roll tracks. The game and its corresponding dissociative hand movements are different, but the play might as well be the same. The sound of the buttons being pressed into plastic is audible even over the music. Stan’s dad Randy pulls out a real guitar and performs a near-perfect Kansas cover. As usual, the kids snub him in favor of watching Stan and Kyle, who shortly after sign with an agent and begin fully devoting themselves to reaching a million points.

To deal with the stress of fame, Stan starts playing “Heroin Hero,” a game where you press the same button over and over again to chase a dragon you’ll never catch, in case they didn’t already convey videogames as mindless, addictive technology. In this world, the only takeaway goal from playing videogames is learning the system and winning. Leveling up to kill a skilled adversary in WoW, impressing your friends with your Guitar Hero skills—it’s hard work, but who the fuck cares? Stan and Kyle reach a million points on Guitar Hero. The screen displays their reward: a homophobic slur. They’ve put their time, effort and soul into a system that only cares if you meet the conditions of an algorithm. Playing the game does nothing but hurt their real lives and egos.

Playing games is more of a barrier to having fun.

So does South Park just have an unhealthy view of videogames, or are videogames unhealthy? Both. In a universe where everything deserves ridicule, childlike games in their purest form remain relatively undestroyed by Stone and Parker’s critical eye. Yes, playing pretend is silly, but being a kid is silly. And being a kid means having fun is your biggest motivation. In “Good Times with Weapons,” the gang doesn’t let a ninja star lodged in Butters’ eye stop them from playing Ninjas. Despite all the bizarre conflict in each episode, by the end, Kenny is alive and well, Randy gave up on [insert temporary Randy fixation here], and everything else is back to normal. What was the purpose of playing, then? It wasn’t to win, gain points or level up. It was to have fun, or even, as Stan and Kyle so often suggest, learn something. In the videogame-focused episodes, playing the games is more of a barrier to having fun than something that is in itself enjoyable. Games are trivial catalysts for short-lived childhood obsession. A week later, you throw it in a pile with the others and forget about it.

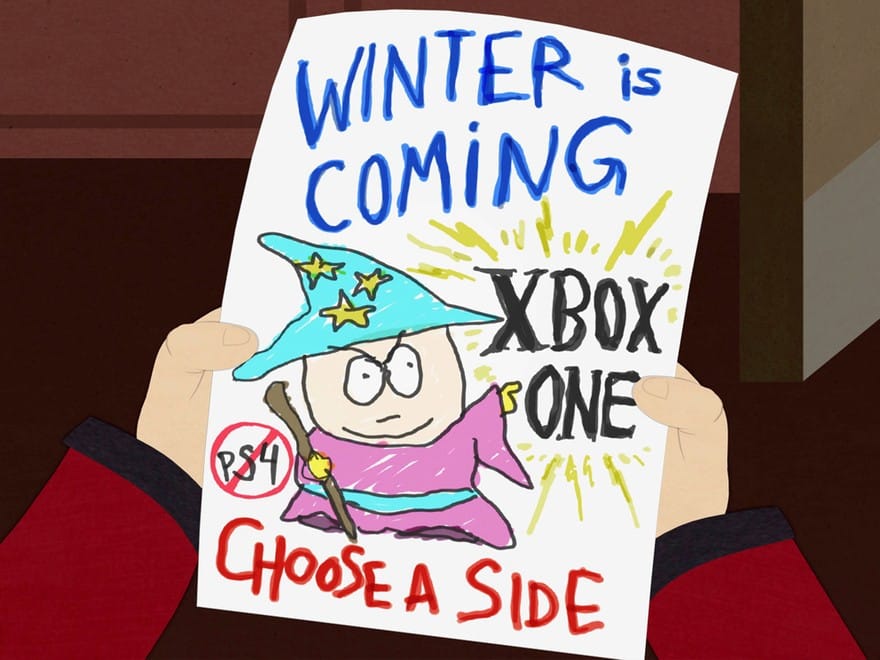

The core of Parker and Stone’s opinion on videogames has remained static. A recent Game of Thrones parody trilogy—“Black Friday,” “A Song of Ass and Fire,” and “Titties and Dragons”— serves as the inspiration for their new game. The overarching plot follows the boys’ quest to obtain discounted next-gen consoles on Black Friday. Unable to agree on a system, they split up: half the kids for the Xbox One and the other for PS4. The boys prepare for battle, roleplaying as Game of Thrones characters, turning the console war into a literal war. The impending showdown between hardware-branded factions is complicated by betrayal, animalistic holiday shoppers, a gang tattoo-clad Bill Gates, and the best part of any South Park episode: a Randy Marsh sideplot.

After a three-episode build-up, the final battle unfolds at the mall. The townsfolk stampede into the mall, ripping apart mall cops and anyone else who gets in their way, not unlike the footage of real Black Friday shoppers shown alongside the battle sequence. Inside the Red Robin next door, one of Cartman’s schemes of betrayal plays out, ending with Bill Gates dismembering Sony’s president, because: it’s South Park. Covered in blood, the winded corporate thug instructs the kids to go get their Xboxes. In a Charlie Brown-esque scene set to the tune of “O Christmas Tree,” the boys buy their discounted consoles. Afterwards, they gather around their new Xboxes, but instead of playing victoriously, they stare blankly at the TV, falling yet again into a state of automated playing. This time, the mood is morose. Instead of continuing their unseen game they go outside, where Cartman declares:

The last two weeks we’ve been too busy to play videogames, and look at what we did. There’s been drama, action, romance … I mean honestly you guys, do we need videogames to play? Maybe we started to rely on Microsoft and Sony so much that we forgot that all we need to play are the simplest things. Like, like this.

[grabs a stick from the ground] We could just play with this. Screw videogames, dude! Who fuckin’ needs them?!

South Park captures the absurdity of media-driven consumerism. While the film and music industries hemorrhage money in the age of digital reproduction, videogames make more than ever. Of all the fruits of American capitalism, the videogame industry is the sweetest of all. Perfect the formula of a franchise and you can make millions reiterating the premise if you can fine-tune the lacquer. The boys keep playing these flashy, high-cost, high-grossing titles on the latest generation of black boxes. And for what?

In “You’re Getting Old,” when Stan’s loses childhood’s indestructible optimism, he summarizes L.A Noire with three statements. After the boys’ epic black friday battle, they are equally as jaded:

Cartman: The interface is pretty cool. See, I told you guys, it’s really a… it’s a seamless interface.

Stan: Yes, it is.

Butters: The graphics are definitely like 10% better than the old Xbox.

Jimmy: Yeah that’s that’s that’s pretty nice.

After this monotone exchange, while Cartman brandishes a stick in the air and declares his newfound hatred of video games, the cover for The Stick of Truth pops up, “Coming Soon!” Since the rest of the episode preaches the disastrous side effects of consumerism, maybe Trey Parker and Matt Stone are reinforcing the satire with this ending, or maybe they’re exploiting the mechanics of a system they love and know how to win. More than likely, it’s both.

South Park is one of the cultural institutions they were built to destroy.

Culture conceived with the intent of being controversial or counterculture has a tendency to come full circle. Sixteen years after Cartman’s alien abduction, South Park is one of the cultural institutions they were built to destroy. If videogames pander to the population with gimmicky, addictive design for the endgame of making millions of dollars, what is South Park doing? They’re making hundred of millions of dollars doing variations of what they’ve done from the beginning. They’ve gotten better at what they do, but they haven’t grown up.

As intelligent as Trey Parker and Matt Stone may be, their sense of humor remains puerile. Most of us are privileged enough to merely squirm in discomfort when we hear the word “faggot,” or any of the molestation jokes, blatant sexism and racism on the show—all signifiers of offense we know are wrong, but often shove down and watch anyway. It becomes more than discomfort if that joke reminds you of the reality you’re forced to live as a queer person, a survivor of abuse or a person of color. Much of this is laughed off as satire, but, on the other hand, an audience of 3.37 million watched the season 14 premiere. For a show obsessed with playing both sides against each other, Cartman’s hatefulness is almost never counteracted, and many of those millions of viewers are left only with hatespeech as catchphrases. And those catchphrases make money.

We have learned to say, “Well, it’s South Park, what more do you expect?” I thought expected more of Trey Parker and Matt Stone, but I really don’t. South Park will end someday, and hopefully whatever takes its place will be a step forward rather than backwards. They built a brand on “Whateva, I do what I want.” And whatever, they’ll do what they want. They’ll do what they want because people will buy it no matter what. We all put up with a lot of crap from our entertainment. Overt offensiveness, recycled plots, unimaginative dialogue, all covered over with flashy visuals. But hey: it’s a videogame, what more do you expect?

From daily Candy Crush habits to yearly Madden fixes, we’re all hooked, and the numbers are only rising. Even though they’re wrong about a lot of things, Parker and Stone are right about videogames. I wish I could call their distaste for the medium wrong-footed, but more and more people within the medium are realizing that there’s a deficit here. Recently, at Indiecade East Paolo Pedercini made most of the same points without a single poop joke. He ended his talk with an important note: “Computer games need to learn from their non-digital counterparts to be loose interfaces between people.” Videogames have strayed too far from the games South Park captures so well. Games played not to win, but to have fun, and maybe learn something. The only thing they shouldn’t be is what they are now: addictive obstacles rather than the facilitators of imagination they could be. South Park will never change, but videogames can.