Upsilon Circuit just might be truly groundbreaking, a tentpole moment that will redefine our relationship with games as both player and spectator. Or it could be an unplayable mess. It’s too soon to tell.

One thing is clear: Developer Robot Loves Kitty has an idea. It’s an ambitious one. And, dammit, they are going to see it through: a free-to-play action RPG that is also a game show, where the audience has total control over the game experience. And when you die, you can never play again.

The idea of in-game audience participation is not totally unprecedented. Livestreamers often find ways for their viewers to influence gameplay, especially where simple decisions can greatly affect the trajectory of the game, as in the Mass Effect and Fallout series. But gathering consensus on whether or not to murder a local merchant and steal everything in his shop has diminishing returns in terms of variety and engagement.

Back in February of this year, Twitch Plays Pokemon took audience participation to the next level by actually putting the controller into the hands of Twitch viewers. Or, more accurately, by putting one controller in the hands of 10,000 Twitch viewers, in the process creating an increasingly popular notion of “crowd-playing” games. The game experience wasn’t exactly “fun,” but that wasn’t the point. TPP forced a new concept within the parameters of a pre-existing system, like tweaking an electric guitar to sound like a flute. What Robot Loves Kitty wants to do is take apart the guitar and the flute and create a whole new instrument.

“Action RPG? Been done. Networked RPG? No Problem. Livestreaming? Already established,” says Calvin Goble of Robot Loves Kitty. “We are using a lot of technology that is very well understood to build a new kind of experience.”

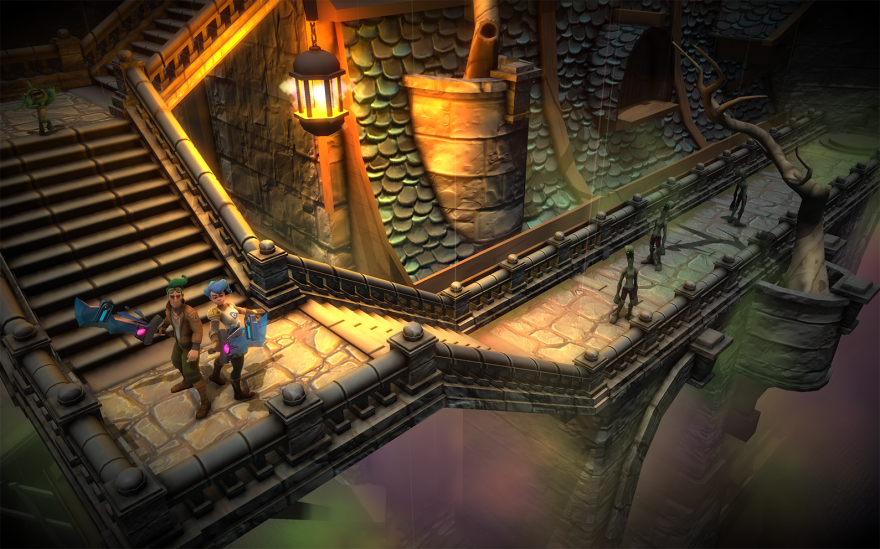

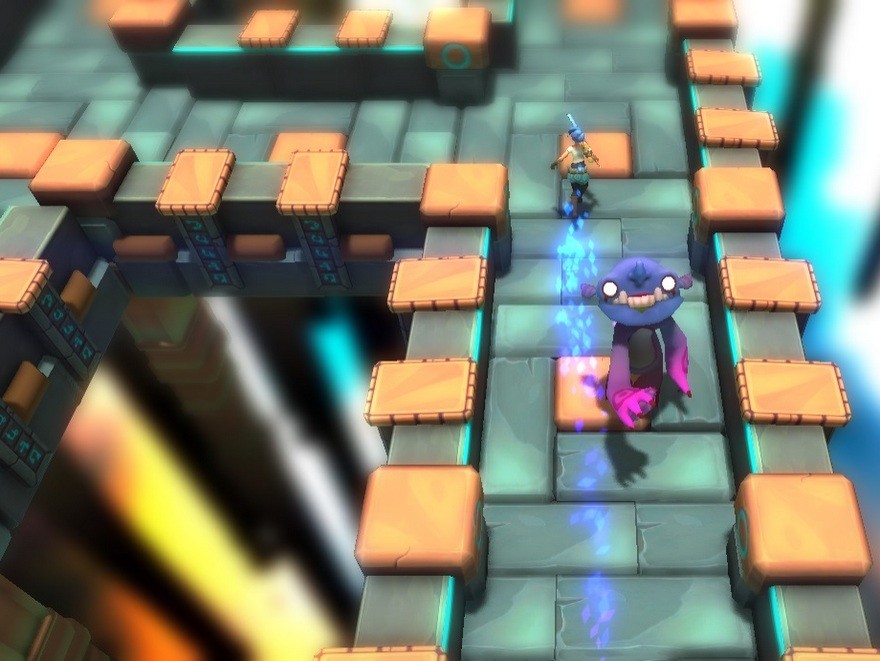

Imagine tuning into a game every day at a set time, just as you would a television show (just as some people already do for their favorite livestreamers). Once the audience is assembled, eight players are chosen to play what looks to be a fairly traditional hack-n-slash RPG. Only every time a player gains XP, the points are disseminated amongst the audience, and each viewer gets to choose how to spend their fraction of a point. Audience members can also purchase armor, weapons, potions and other times to help their favorite character along the way, effectively leveling up characters from above like some divine consciousness. Or like in The Hunger Games.

Here is the kicker: players who make it through that day are invited to come back the next day and continue where they left off. Players who die are done, as for good. An audience member is selected to replace them. They can never play the game again, ever.

“We started thinking about permanence in games,” says Goble. “Real, meaningful death.”

All of this is presided over by “host” Ronny Raygon, a Max Headroom-esque digital personality who will act as live commentator and add to the world building of the game itself. It’s this lore that Robot Loves Kitty hopes will keep people coming back. Set in an alternate mid-80s where Manhattan suddenly disappears, players will be looking for something called “Dream Tech Crystals.” Why Manhattan just straight-up left, and what the Dream Tech Crystals do is all still under wraps. But the mystery will be slowly revealed as the game proceeds every day over the course of “a year or more.” After that, everything ends.

“Just like permadeath, there is a permanent game.”

Upsilon Circuit is an undoubtedly exciting concept. But at the same time it’s hard not to worry that Robot Loves Kitty has bitten off more than they can chew.

Forget for a moment about the technical challenges involved in creating a new, comprehensive platform that will allow for such a level of audience interaction. Goble says he is in talks with existing livestreaming sites, or they will host their own. Either way, he is confident it can be done.

The bigger problem is for Upsilon Circuit to be successful, it will require consistent, earnest participation from people on the internet. Always a risky venture. Goble admits the game will needs a “huge audience” to function as designed, and that audience will have to tune in every single day for a year. What if a player wins out on Monday but has to go to work on Tuesday and can’t continue playing? And what about trolls? The trolls will flock to Upsilon Circuit as if it were some great monolith.

Then there is Ronny Raygon, who was present at the PAX demo via a giant screen, his dialogue controlled by someone hidden in the back of the booth. He spouted one-liners at passers by, insulted and encouraged players in equal measure. A lot of his stuff was good. He interrupted my interview to say, “Give me a pen and paper so I can be as important as the guy in the skinny jeans wearing a media badge.” But after a while the shtick started to wear off. It will be another challenge to include Raygon in a fun and purposeful way without having him dominate the show.

Intelligent audience participation through live streaming is an inevitability. And I want Upsilon Circuit to be the one to take us there. The personalities behind the game, the enthusiasm and ambition of its creators are all in the right place. There just might have to be a few growing pains before Ronny Raygon becomes a household name.