How one British library is using the game tools to craft awe-inspiring virtual environments

When I think of the future of maps, I think about my old road atlas, the large, accordion-folded sheet of paper of the Great State of Alabama, covered with county roads and highways and twisty rivulets and interstates like arteries, and how it has long been replaced by my G.P.S. But when Tom Harper, Curator of Cartographic Materials at the British Library, thinks about the future of maps, he thinks about videogames.

He and the Museum have partnered with Crytek, creators of the ultra-realistic Crysis shooters, to jumpstart a project called Off The Map, in which university students will use the game tools to craft awe-inspiring virtual environments. We talked to Harper about a new era of interactive mapmaking.

– – –

Kill Screen: What got you and the Museum interested in videogames and virtual maps?

Tom Harper, Curator of Cartographic Materials: It’s quite an unusual collection here at the British Library. We’ve got the national collection of books, manuscripts, and importantly, maps, four-and-a-half million maps, many historical. Some of them are very very old. Two thousand years old. For us to get into a competition with a videogame company to create a videogame, it seems tacky, it seems novel, it seems unusual, but from my point of view, it made perfect sense.

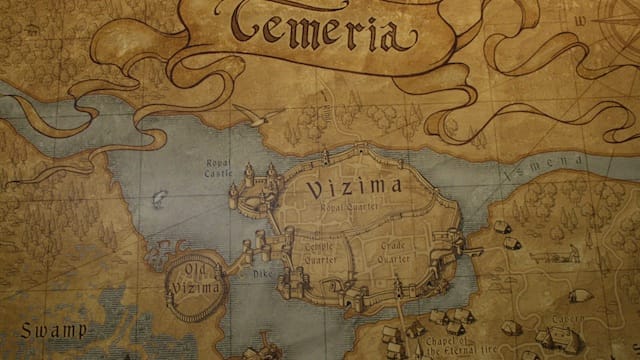

We chose three sites, the Tower of London, the Pyramids in Egypt, and Stonehenge — historically important, evocative places, which predate any sort of memory. But they’ve been well-documented. I chose from the British Library collection top-down maps, bird’s-eye views, photographs, I wasn’t able to get and poetry, a number of different objects showing different angles, viewpoints, aspects, and gave them to the students. The idea is they put them together and create a world out of it.

The importance of computer games, game arts, and videogames to maps has been there the last thirty years. Look at SimCity, 1989.

So the students will be using Crysis’s CryENGINE 3. What do you think of it?

It’s just astonishing that it’s able to create such convincing worlds right down to a water droplet on a leaf underneath these colossal superstructures. The level of detail is just amazing. I deal everyday with mapmakers from the 15th Century who were using the best tools they’ve got. They’re using triangulation, early telescopes, engraving tools and pens an the latest technology. Just imagining what they’d make with what is possible today, it’s just astonishing.

How did maps arrive at this point of interactivity throughout history?

The idea of recreating your surroundings in some form by making marks on something is timeless. Some of the very earliest maps are cave paintings. Rock art. We’re talking at least 15,000 B.C. It was the Romans who began to come up with scientifically-measured maps around the 2nd Century. The Roman Empire kicked it off. They were good at everything. They were good at gaining territory, and good at mapping it. But as Rome started to fall into ruin, so did mapmaking. It’s only in the 15th Century Renaissance that people started to need to make maps. Around that time you got printing technology. The first printing in Western Europe was in the 1440s. The first maps were printed in the 1470s. These were printed using wood and then with metal plates on paper. That’s really how things developed until the 19th Century.

Do you feel like new technologies, things like Google Maps and G.P.S., have been detrimental to the field of cartography?

Not at all. Digital maps have been being produced since the 1970s, when traditional mapmaking methods become less useful to the main map agencies. But no. People will always use the best techniques and the best tools. That’s been the case throughout the history of civilization. If you’re talking about traditional mapmaking methods falling into ruin because they aren’t used. . . that’s how things go, isn’t it?

An author called Simon Garfield has written a really good book called On the Map. One of his lines is that Google Maps is such a good map interface that eventually its ability to capture the world will be so accurate that it will be the end of maps. Maps would be perfect. We can all go home. I don’t think that’s true. They’re always going to be different purposes for maps.

Is that something that the collaboration with Crytek aims to do? To help expand the field of maps?

The students are going to create art and entirely new maps. 3D virtual environments can be explored. That adds something. Yes. But actually, the importance of computer games, game arts, and videogames to maps has been there the last thirty years. Look at SimCity, 1989. We create maps to understand our world better, and that’s exactly what this project is doing. It’s not just a one way process. The virtual world is feeding back into the real world as well. The scenery you see in the backdrops of games like Grand Theft Auto are very important landscapes which have elements of the real-world and elements of fantasy. There has been a lot of academic study on the landscape of videogames.

It’s all perfectly appropriate. It’s all maps.