Rohrer had spent the previous two months designing and fabricating his now lost game, teaching an A.I. to play it, and sealing it’s components in airtight glass. Forged of practically indestructible titanium,

A Game for Someone is buried a couple of feet under prairie dirt, begging to be unearthed. This is all part of the perverse scavenger hunt Rohrer dreamt up. All we know is that the game is located a few miles from the road on public land in Nevada, at one of literally a million GPS coordinate points.Rohrer, who claims that he himself isn’t even sure of the game’s exact whereabouts, believes it probably won’t turn up. “It’s so much work to go find this thing,” he says. “People aren’t going to do it. It requires a plane ticket, a rental car, buying a metal detector, a GPS. It’s an expedition!”

So, we called him on it.

Like any good scavenger hunt, we need the proper tools. And also, plenty of spare cash. A ticket to Vegas would cost me about $700, and a hotel room in a small town such as Mesquite (population 15,400) or Fernley (19,300) would run around $60 a night. As Rohrer said, I’d need a rental car to get around. The cheapest, a Kia Rio, is $22 a day. We’re talking a pricy $1,300 for the week. But realistically this could take months, even years. I’d do better budget-wise stocking up on pork and beans at Costco and driving across the country myself.

But clearly, I can’t do this alone, so I called in some experts. I rang a Nevada-based metal detecting club, to see if it was even remotely possible to find this thing. The guy who answered wasn’t in the mood to talk, but gave me the number of his treasure-hunting buddy, a sympathetic prospector from neighboring Arizona. He advised me to pack plenty of water, food rations, and camping gear, and highly recommended securing a four-wheel drive pickup, so that I could sleep in the truck bed. When he asked my battle plan, I told him that I knew it was buried somewhere on public land.

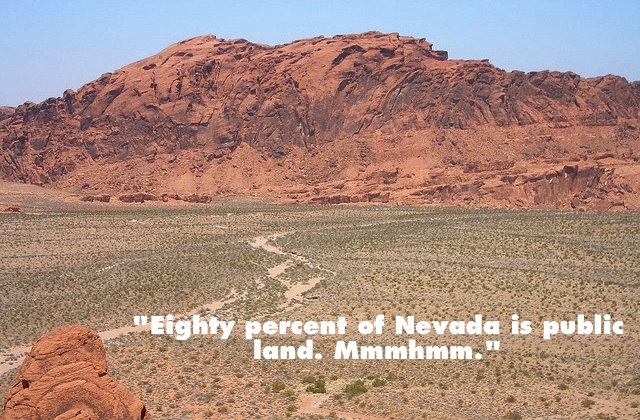

“Eighty percent of Nevada is public land. Mmmhmm. It’s possible, but highly unlikely,” he said.

So who has the most public land? The state and federal government, of course. I decided to phone a deputy ranger at Valley of Fire, an inhospitable stretch of dry craggy badland with jagged red sandstone formations jutting up. It’s one of Nevada’s oldest state parks. He told me not to uproot any natural resources and to watch out for bears and dangerous plant life. “People fall into cactuses sometime. And there’s datura, which is poisonous, if you ingest it,” he said. Ok, don’t eat random plants. Check.

Also, it turns out it’s impermissible to use a metal detector in a state park in Nevada without the written consent of a park ranger, according to his secretary Elise. I’ll have to update my stationary.

Things weren’t looking too good, but, undeterred, I called up a bounty hunter named Brian, who was referred to me by a bail bondsman in Reno, to see if he could help out. Admittedly, I was a little apprehensive about talking with a burly dude who specializes in wrangling in wanted men, and felt relieved when a tickled woman picked up.

–Hello.

–Yeah, I was wondering if you guys could help me track down a board game that’s buried in the desert?

–Uh, a what?

–This guy has buried something in the desert in Nevada and I was wondering if you guys could go look for it for me.

–No sir, we won’t do that… laughing.

–So tracking personal objects isn’t a thing you do?

–We don’t do anything like that… laughing.

Well, so much for that.

I get the feeling Rohrer is secretly hoping

A Game for Someone remains undetected for a very long time. “If this is going to be found at all, it will be found in two months. If not, it will only be found by, like, aliens in a way-distant future,” he laughs. It’s still missing in action, and it looks like he will get his wish.

But Rohrer’s a realist if anything and admits there are a few other possibilities besides an alien discovery. “Someone could stumble upon it through erosion or rainstorms in twenty years, when a rancher will be chasing after a cow and step on it,” he says.

“There’s also the idea that ubiquitous aerial drones are coming, and someone will easily be able to program one to visit a million coordinates. But I actually don’t believe that. It’s just hype, like flying cars.” Also, dolphins. “It becomes a different game,” he says, “for somebody who can potentially see through titanium.”

Luckily, the instructions are written in abstract diagrams, so they can hopefully be understood by someone or something besides us. But it’s not perfect. “Some of these things I had to punt on,” Rohrer says. “How can I explain what a game is diagrammatically? How can I explain why two players would want to sit down across from each other with this piece of metal between them to determine a winner? How do you convey that you want to be the winner? Do you draw a star?”

There’s one other question he forgot to ask. Is the game actually any good? Rohrer is quick to admit that he isn’t sure. “You know, I’ve never played it!”