What does it mean to be an indie game dev in Latin America?

Everything that surrounds Daniel Benmergui feels and sounds like fiction.

The day that I went to see Benmergui in Buenos Aires, Argentina, I was late, so I took a taxi. Some minutes later, when I asked the driver if we were near, he answered me with a question.

—Why are you going there at this hour? People usually go there for dining, not for lunch.

—Yeah, I know, but I’m seeing someone who works there.

—Who works inside a coffeeshop? What’s his name? —he asked me.

—Daniel…

—Daniel Benmergui?

I was shocked. Was he so famous that cab drivers know about him?

—Yes —I answered. Do you know him? Have you played his games?

—Yes. Actually, I’m his father-in-law.

Buenos Aires is a metropolis of 3 million people. There are around 40,000 cabs that are constantly moving people all over the city. Meeting Daniel’s father-in-law while going to see him was almost impossible. Some minutes later, when we arrived at El Faro— the coffeeshop where he works on his games—the taxi driver and I went out of the car and entered together. The face of Benmergui when he saw us was of total disbelief.

II

People say Buenos Aires is a European city within Latin America. Its architecture is different from the modern Santiago, in Chile, and the business-oriented Sao Paulo, in Brazil. It’s divided into 48 neighborhoods, each one with its own identity. For example, San Telmo is near the city center and has traditional buildings, while Palermo is an upscale place, with boutiques and fancy restaurants. Buenos Aires cultural life is one of the most restless in the region. There are film festivals, plays and concerts throughout the year, and November wasn’t the exception, as the EVA (Exposición de Videojuegos Argentinos)—the most important Argentinian game convention—took place. It was its eleventh year and it was held inside a movie theater.

The EVA was organized by the ADVA, the Argentinian Game Developers Association. It gathers around 30 game studios in the country and works with the government promoting their industry. In recent years, Argentinian game studios have been at events like GDC or gamescom and are now developing for mobile, web, PC and consoles. But what is more interesting is the Argentinian indie game scene, and Daniel Benmergui is its flagship.

Benmergui works inside the coffeeshop El Faro just because he needs to work in a different space than where he sleeps. It’s just five blocks away from his house (which he shares with his parents) and it’s a quiet place. “It’s not like other places where at 3 p.m. there are a lot of old ladies yelling at each other. Here, I can get to work.” In front of him there’s a laptop and a cup of coffee. He is a typical Argentinian guy, with a rough look and a great love for beef. Nobody would think that he had won the IGF 2012 Nuovo Award, a man who constantly tinkers with game mechanics in order to wring meaning from them.

It all started at GDC 2005. It was Benmergui’s first time at the conference. “At that time, it was big enough so the people you wanted to see could go, and small enough so you could get near and talk to them.” But when he got there, he didn’t have anything to show while other indie game devs were showcasing their next big thing. When he returned to Argentina, he was depressed. He knew that he needed to change something in his life, and some time later, he quit his job at Gameloft, where we was a technical director.

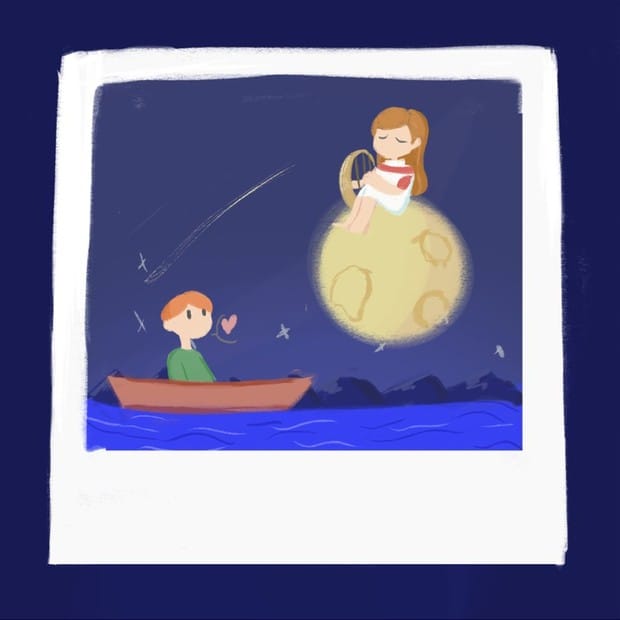

He had savings for a year, and that was it. He spent the next months working on a prototype, but also released I Wish I Were the Moon (2008). In it, the player has the power to take a character— or object—and move it around the screen in order to create new interactions between them. It’s a tale of two lovers on a quiet full moon night, and the player can decide if the relationship will have a sad or happy ending. A question usually arises in the mind of the player while trying this game: “Can I make something to change the course of the story?” As soon as Benmergui released it on Kongregate, it exploded—today it has more than half a million plays. The next year at GDC, people knew who this Argentinian guy was.

After that, he secretly began work on a prototype game, but he also released Today I Die, in which the player creates an interactive poem. By changing adjectives in the poem, the scenario switches, and new actions become available. It’s a short game, but one that ties the game’s mechanics closely with its meaning. For Benmergui, making a game is an opportunity to ask questions about human emotions: love, hatred, envy. This focus began, like a lot of things, with Braid, and Jonathan Blow, who gave a talk about games with meaning at the Experimental Game Showcase at GDC.The day after our meeting, at the EVA, Benmergui would give his own talk about Braid and on how the game mechanics are connected with its backstory.

In Latin America, the common belief is that it’s not good to share your ideas, as others will steal it from you.

It’s an important message for any group of developers, but the Argentinian indie scene is uniquely positioned to create artistic leaps. It wasn’t always that way. Many Latin indie game devs are self-taught professionals, as there are not many game-oriented careers. For a long time, everybody was on his or her own, working on small projects and not sharing information with anyone: there weren’t many spaces for people to collaborate. It was also a cultural issue. In Latin America, the common belief is that it’s not good to share your ideas in order to get feedback, as others will steal it from you. But that has been changing in recent years, as people saw that they weren’t competing with each other and they needed to work together in order to bring their games to the World. There are more work spaces, like the Game Work Jam, where people with experience on game development organize events around Argentina for people to come with their ongoing projects and receive help from people. The EVA is also an example of this, as companies have worked together to bring the best speakers and have the best program each year.

Still, there’s room for improvement. “In Latin America, people don’t know how to negotiate,” Benmergui told me. As there aren’t many success stories; Latin game devs do not know how much to charge for a game or how good a deal is. Benmergui says that helping the indies in Argentina and in Latin America is not only an option for him but a moral obligation.

A week before I met him at El Faro, he organized with a local production house an event for game developers. He got in touch with people like Zach Gage, Ron Carmel, Nathan Vella, Lee Patty and Tim Schafer and invited them to give some talks and workshops. For Benmergui, it was like bringing a part of GDC to Buenos Aires. It was a way to show what people were doing in another place and how it is not impossible to do the same in Latin America.

III

Agustín Pérez (also known as Tembac) is another Argentinian indie game developer. I met him at the indie game space that he organized at the EVA. There, around 30 indie game devs were showcasing early prototypes. Tembac met Daniel Benmergui after he won a game dev contest called CODEAR that was organized by Benmergui through a forum. Some months later, they became close friends and began working together at Tembac’s place. At the indie showcase there were developers from different parts of Argentina and games for different platforms: mobile, PC, and Oculus Rift, among others.

What does it mean to make an Argentinian or a Latin game?

One of the indie games shown on the lower floor of the theater, was special: an arcade cabinet called NAVE. It’s a survival space shooter with retro graphics that was on tour for several months across Argentina. If it’s difficult to make an indie game and obtain success, it’s even more difficult to create an arcade cabinet that you need to transport to exhibitions for people to play. NAVE is a love letter to old school videogames, but it’s also a testament to how far the Argentinian scene has come. But why hasn’t it received more attention? The problem in Argentina is the same in Brazil, Chile, Colombia and Peru. There are people making games and people who want to play their games within their countries, but there is not a local market for them to buy them, easily.

What is needed for a local market of consumers to appear? Benmergui talks about three factors: an easy way to charge money, a reasonable price and games that Latin people would like to play. Buying games from Steam is reserved for people with a credit card; to have success in the Latin market you need something more convenient. Also, because of lower incomes in Latin America, prices of games need to be lower in order to attract a good audience. And finally, people want to play great games that make a connection with them. What does it mean to make an Argentinian or a Latin game? It doesn’t mean to make games about tango, or beef, or about the Inca culture. It’s about the sensitivity of Latin people, not about using clichés.

In 2008, after leaving Gameloft, Benmergui started working on Storyteller, his first commercial project. It was a game about building stories. In the meantime, he made I Wish I Were the Moon and Today I Die, but his big project was always Storyteller. After making these two games, he got back to work on Storyteller, but he couldn’t move on; he was missing something. In 2011 he stumbled upon Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics and found what he was looking for: the concept of closure, and how we tend to finish incomplete figures or stories and fill the gaps. After that, he started working again on the project and got to finish another prototype, which won the IGF 2012 Nuovo Award. And talking about his life, Benmergui decided to return to live with his parents and also found a philanthropist, who gives him a regular amount of money each month to cover his expenses. It’s an almost fairy tale conclusion to his saga.

The game has changed a lot since last year. In that version much of the game was based on “soft skills,” but there wasn’t any logic on some puzzles. Now, there is a logic to Storyteller—one that comes from Benmergui’s thoughts about life and the sensitivity of the Latin character. He says that players understand how to make stories within the framework of the game. It has been a challenge to simplify human emotions such as love, hatred or jealousy. The game presents on each level a phrase, with the end of the story, and a bunch of squares, like a comic strip, that the player needs to fill with characters or objects.

Daniel Benmergui thinks that people are very good at consuming stories. With Storyteller, he’ll teach them what he’s gotten so good at: creating them.

Image of Buenos Aires via Gobierno de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires

Image of I Wish I were the Moon via Mila F.

Images of Benmergui and Storyteller courtesy of Daniel Benmergui