Robbie Cooper has spent the last five years watching others stare at screens. As part of his Immersion project, he has filmed babies, teenagers, the middle-aged and the elderly transfixed in the glow of one monitor or another. Using a special camera, Cooper’s work offers a vantage from beyond the glass. The results startle and amuse; for all the time we spend in front of our computers or tellies, we rarely if ever see ourselves from the screen’s perspective. The audience becomes the performer, whose performance is being an audience.

What began as a series of exhibitions is being published as a forthcoming book. With your help, the project hopes to expand even further. Starting later this year, Cooper and collaborator Jeff Watson will launch a website allowing anyone to record and document their own screen-time. Cooper envisions a massive archive of images that capture, in snapshots and video, a sample of our collective experience as 21st century watchers.

I reached out via email to find out more. Cooper says one community he’s intrigued by are Guilds or Clans playing massively multiplayer online games together. He hopes to capture the many ephemeral stories taking place every day, from within and without the game-worlds these players inhabit. If that’s you, get in touch.

Kill Screen: When did you first come up with the idea for Immersion?

Robbie Cooper: I was in China and Korea doing a project on virtual worlds. Some of the internet cafés, particularly in China, are huge; you can see row upon row of people sitting at screens. It was visually a dramatic way to see it. In the west there’s just as many people sitting at screens, but they’re sitting in the office or in their house.

I’m a fan of Errol Morris, so seeing that made me think of his Interrotron method, as a way to capture screen interaction.

Your Kickstarter video quotes a statistic that we spend 6 hours a day in front of a screen. Did you start your project with a bias regarding the positive or negative effects such screen-time has in our lives?

I never thought of it as being one or the other. It was immediately obvious it was both. In my own life, it’s both. I’m currently thinking I may get rid of my iPhone altogether, just because it’s one too many screens. But if I had no laptop, I’d feel disconnected in a bad way.

As far as the project goes, I’d like it to have moments of darkness, definitely. Also humour and all the other things that you need in something that’s satisfying. It deserves to be done comprehensively. I’m not a scientist; I’m inspired by science. The ambition of coming out the other end with a fixed answer as to how this affects us would be crazy. But as a way of organizing information, visual information and so on, it’s interesting and useful.

You’ve been working on this project for five years now. What has surprised you the most? Any particular reactions that stand out?

One woman laughed as she watched a Mexican Zeta (drug cartel) soldier’s head fall of in a real torture and execution scene. Which was initially surprising. But then I realized she was having a hard time processing it. We don’t always react the way we think we’re going to when we’re genuinely shocked.

Have you found patterns in how certain demographics respond to certain content?

Older people tend to be much more contained, whilst youngsters are frequently wide open, of course! Watching a youngster on the monitor while they’re playing or watching TV can be entertaining. You get a clear idea of who they are, without a single word being spoken. You can put a kid in front of a screen for 30 seconds and they’ve told you everything about them. Mothers watching their own kids on the monitor have been quite shocked, mesmerized.

Very young kids unconsciously imitate what they’re watching. It’s hilarious to see a toddler’s expression change as they imitate, say, an adult character, after imitating a child character. Middle aged and older people have a lot of things that they’re familiar with. It’s harder to find something fresh that they want to see and really get into.

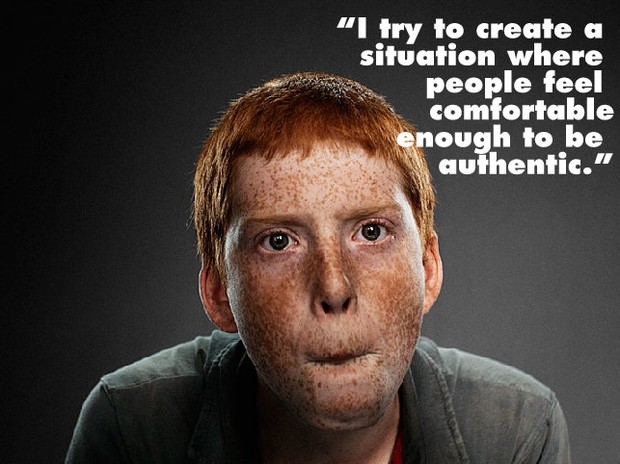

At my shoots I don’t force people to watch anything in particular. They choose from amongst [many different] topics. I try and create a situation where people feel comfortable enough to be authentic. If we can assemble enough material, organizing it after the fact may visually express patterns just in the choices people have made and so on.

The next step for Immersion is giving others the tools to record their own screen-time. What risks do you foresee with taking the process out of your hands? How does the project shift, as a piece of art and/or a historical document, when given over to the masses?

A big success would be if there was so much input that my original project just became a part of it. If no one contributes it wouldn’t be a failure; it would only mean that that side of the project didn’t happen. A failure would be if there was no diversity, if it was overwhelmed by one particular pastime.

I’ve got two art books that I particularly love. One is a book of grids of industrial topography by Bernd and Hilla Becher, the other is Atlas by Gerhard Richter. Which is also full of grids. Atlas has a different feel; it contains sketches, polaroids, snapshots and so on. But the way it’s organized gives those things a quality that they wouldn’t have on their own. If the collaborative project were to really succeed, my instinct is the fact there’d be wildly diverse styles and capture methods wouldn’t prevent it from having a very potent beauty.

In hoping to extend your project to record guilds and other online communities, you write that “players [will] record and upload both web cam footage and screen footage to the site.” The use of both player-faces and screen-footage seems quite separate from your original vision, of capturing the story of our viewing from the screen’s perspective. How might showing the source of our reactions heighten or diminish the reactions themselves?

There’s a narrative that is being created by the interaction of people in this world. Which is true of a death match. But in the case of guilds the narrative is much more highly developed and complex. So not showing what’s going on in that world, at all, could render it unwatchable. Not even capturing the screen footage would be a mistake. With the screen footage, I can give clans and guilds something that they value, and which would have a coherent narrative.

I would be interested to know how it looks without screen visuals; I suspect it would be clunky. But I’ll try it. No one’s done either before, which is exciting!

How do you anticipate an online player interacting with others to react differently than a single player interacting with a game’s systems or AI? Or a sporting event they have no direct control over?

I’ve already seen it. A lot of the kids I’ve already shot are playing online or with each other. I usually have about 4 or 5 Xbox’s on a shoot, connected together and online. As we all know it greatly heightens engagement. There’s a level of performance too—people show off to each other a bit and joke about.

[With] sporting events, it HUGELY depends on the match. It can be like watching paint dry. Or a big game can be electrifying, in a very different way to an online game. An online game you can always start again. A big match is history being made. Each moment passing will never happen again. I find myself wondering if a big guild or clan event will have that same quality.

What do you spend your time watching/playing? Any films, sports, or games you’re passionate about?

I think my fondest memory of gaming may be the original XCom. I loved it. The new one felt over-simplified. I was astounded that you can’t pick things up off the ground, for example. Running out of ammo was a big problem in the original. So you’d be forced to send soldiers running for ammo, or throw ammo from one soldier to another. That felt real because it was a situation that arose due to circumstances.

I don’t understand sports on TV at all. But I did get into the Olympics. When we Brits won so much, I was blown away. Close to tears actually, a couple of times. Mo Farrah and Jessica Ennis both seemed like they’d been transported somewhere amazing in themselves […] and there was a general feeling like we were sharing it with them.