Where painting and videogames collide

If someone refuses to paint, all you need to do to fix that is strap tubes of the stuff to the soles of their shoes and send a couple of angry dobermans after them. Don’t question why you’d ever be so desperate to get someone to paint that you’d resort to this admittedly drastic method. This is how art is made. At least, according to Splattershmup, that is: through peer pressure and, failing that, hostile encouragement.

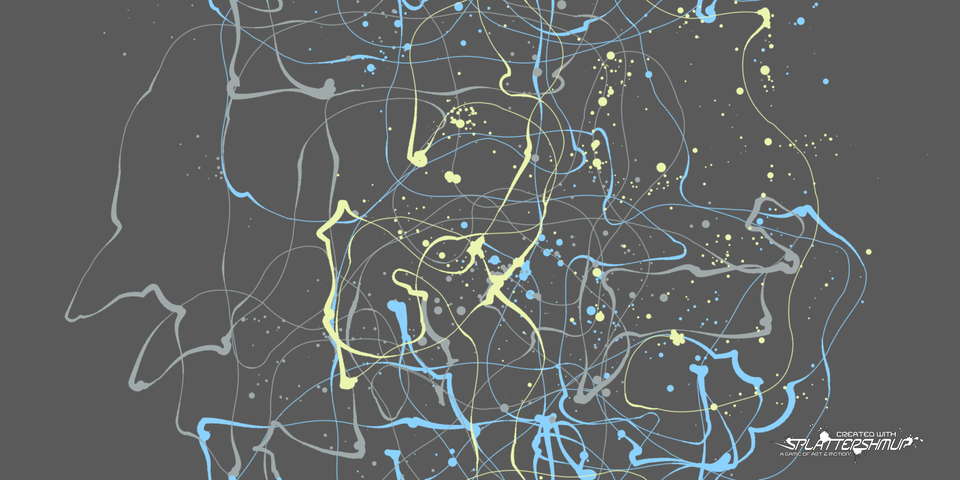

In truth, Splattershmup isn’t as goofy as that (or its title) makes it sound. It’s an honest and successful attempt by Rochester Institute of Technology’s MAGIC Spell Studios at exploring the “intersection of the classic shoot-em-up (or ‘shmup’) arcade game and gesturalized abstraction or ‘action painting.'” This means that, as you’re steering a ship from a top-down perspective, shooting the enemy ships that rush you, you’re also actively painting. Your ship trails paint as you move it around the grey floor of the gamespace while dodging bullets. You occasionally get pick-ups that change the color of this paint. Once you die, you get to see the streaky composition you made in full, and can easily save it to your computer or share it on social media.

action painters have an “encounter” with the canvas

The comparison to action painting works as the painting side of the game is involuntary; a byproduct of playing the game. Your urgent concern isn’t what you’re painting but making sure your ship doesn’t eat a thousand bullets and blow up. The process of action painting itself is similar. It’s a term coined in 1952 by art critic Harold Rosenberg in his essay “The American Action Painters.” He applied the term when describing the works of abstract expressionists such as, most famously, Jackson Pollock. Rosenberg says the action painters have an “encounter” with the canvas, adding that, to them, it was “an arena in which to act.” These painters, according to Rosenberg, captured an immediate moment of emotion, letting paint drip and smear spontaneously, rather than sticking to the typical method of bringing a planned image to life with their brush.

You can see through the language that Rosenberg uses that the jump to turning action painting into a videogame isn’t a big one. The idea of it being an “arena” makes a direct connection to shmups in particular. They often confine you in a space and send waves of enemies for you to deal with, using fast-motion to avoid incoming fire—it’s a performance of skill. Action painting quite easily transfers to the shmup format.

But it’s worth noting that Splattershmup isn’t the only game to have explored this translation from painting to videogame. Ian MacLarty’s 2014 title Action Painting Pro used the format of a 2D platformer to recreate the process of action painting. In it, you moved a character around, leaping from platform-to-platform, the catch being that the platforms constantly shifted position. While doing this, the character leaked paint onto the backdrop of the gamespace, it running down the walls as a rainbow assortment.

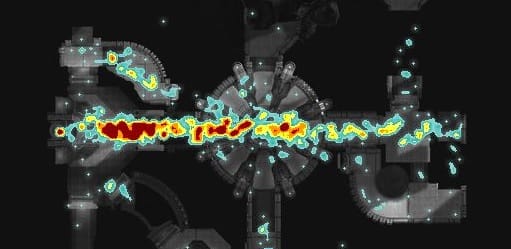

Before even this, though, there were the Halo 3 heat maps back in 2007. These were overhead plans of the multiplayer maps of the first-person shooter that displayed data as blotches of color. This data included player deaths and kills around each map. If a certain spot was dark red it meant that it was a place of frequent death-dealing, while less busy areas were orange, yellow, green, or had no color at all. The idea was to use this visual data as a way to improve your tactics in-game but it also doubled up as an unusual means of collaborative action painting.

You can download a beta version of Splattershmup on its website.