Street art is part of the cultural mainstream. Banksy and Neckface are household names, fetching tens of thousands of dollars at auction. Muncipalities commission graffiti artists for grand sums to produce public art.

And gaming has embraced the medium enthusiastically. Last month, Sega rereleased 2000s Jet Set Radio – arguably the first graffiti-based game. Let’s take a look back at the growth of street culture inside the video game world over the past twelve years.

Jet Set Radio was great not only because of its pioneering cell-shaded graphics, but because it was the first game to make tagging fun. Playing as Beat and other characters in the Graffiti Gang, there was an extended in-game battle between the taggers and an over-zealous police force. The ridiculous consequences for tagging a building in the game satirize real-world police brutality, as a couple sprays from a can of paint can easily get you tackled by an entire squad.

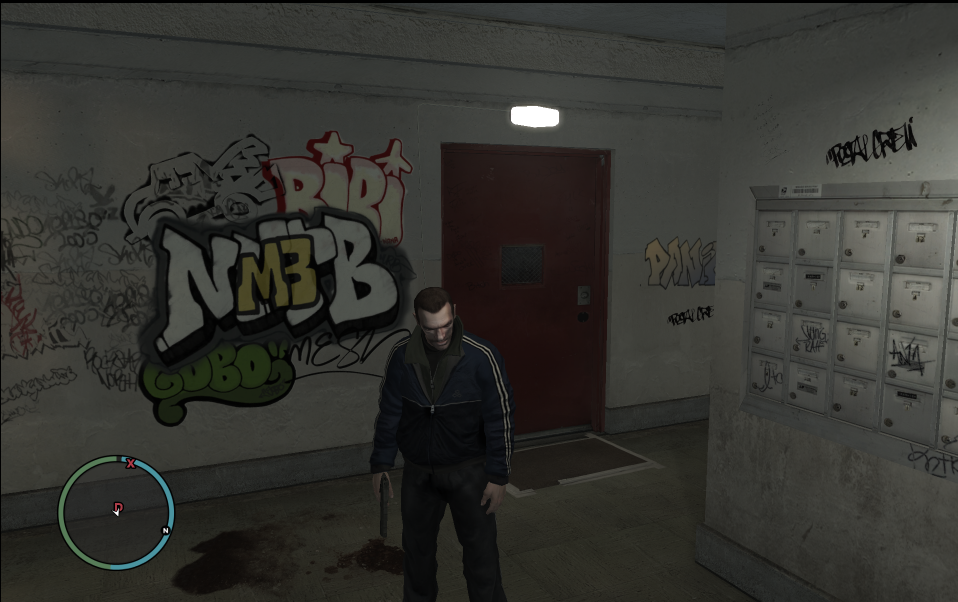

Grand Theft Auto offers street art partially as a location marker, and partially to add to the game’s humor and heritage. One of the repeated tags in GTA IV is “VICE” in big bubble letters, an easter egg referring to a previous game in the series, and possibly to the Grove Street Gang’s tags from San Andreas. Another common tag is “Indie”, a tag of the NYC-based street artist Indie184, who was commissioned by Rockstar. Here we see graffiti as a ubiquitous feature of the urban environment.

The No More Heroes series, was most likely named after a 1977 album by the punk band The Stranglers’ 1977. Curiously, there’s a Banksy Los Angeles billboard stencil of Robin (as in, Batman and) next to the title. The stencil element is repeated as a loading scene through the game. No More Heroes’ main character, though, is not a graffitist, just a nerd with an electric katana. Though Banksy might be political, No More Heroes is not.

Sideway: New York is a complete departure from the three previous games. In Sideway, you are the paint. You play the main character, Nox, a street artist sucked into a world of moving graffiti. The two-dimensional to three-dimensional shifting platform game allows you to explore every surface of the building you climb. The game is built solely around the world of paint, where the main character is both the creator and destroyer of his own substance. The main boss known as Spray, a distant ghoul that has captured your friend, is not reprimanding you for tagging buildings, and nothing in the game consciously tries to hinder you from doing so. Similar to No More Heroes, graffiti in this instance has become more about style than about territory or rebellion.

There is something to be said about games where graffiti is simply an extension of gameplay. Minecraft, the most open of game worlds, has mods programmed explicitly for creating graffiti. In a game where everything can be under your control, it’s compelling that people wish to paint tags on the walls of places where the player is the only authority. However, with the games built-in propensity for shareable worlds, Minecraft easily lends itself to community, and also to territorial marking and virtual vandalism. A quick Google search of “Graffiti Minecraft” shows exalted taggers with looping videos of their conquests on host servers, and numerous images of detailed pixel art affixed to player-created landmarks.

A street artist can be considered a visually creative clown, their work humorous and provocative. Beat from Jet Set Radio and Nox from Sideway fit this description, and while Travis from No More Heroes isn’t quite an artist, he and the game world built around him are comical. Grand Theft Auto’s main characters are not humorous, but the game itself is, of course, absurd. Hyperbolic characters and environments allow players to push themselves beyond the realm of the acceptable, into criminal disturbance. But that’s what makes for a good game, right?