This story should have come out last year.

And yet, it’s appropriate that word of a 2013 zine giving voice to a faceless, locked-up crop of 2007 letter-writing EGM fans hasn’t gotten around.

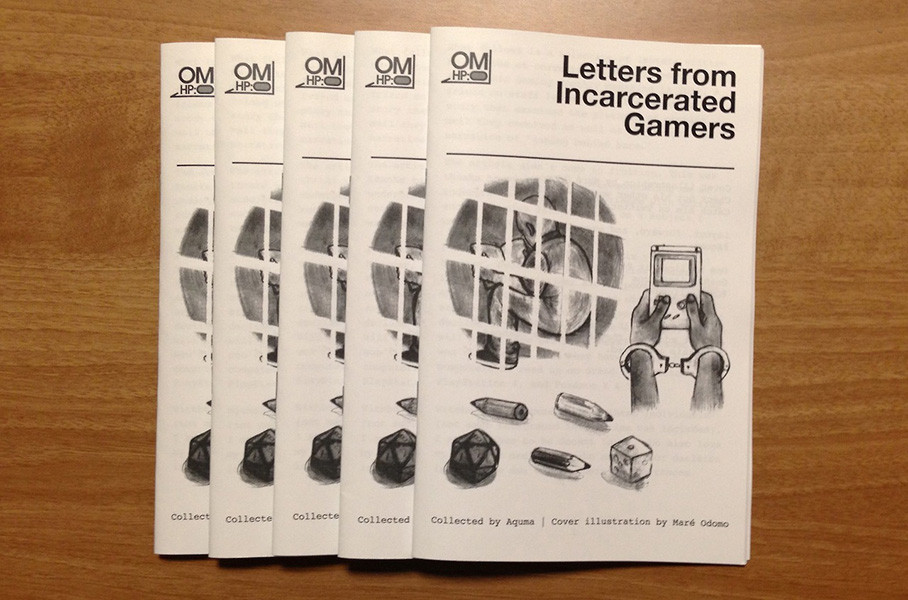

Letters from Incarcerated Gamers, a 23-page compilation that’s exactly what it sounds like, doesn’t demand your attention. You’d easily miss it on a bookshelf. It’s 13 black-and-white Xeroxes of letters from inmates who have done God-knows-what. In fact, the only reason I heard of it myself was because someone mentioned it to me at a GDC party. I had missed it in the convention’s bookstore earlier that day, and I was looking for oddities such as these. Someone had to tell me about it.

I’m just a bit stunned the Internet somehow hadn’t taken hold of this back in 2013 or made this yesterday’s retweet.

But it makes sense.

We, as game players, are an escapist demographic. We play games for lots of reasons.

At their purest, games are simply a sublime way to pass the time.

At their absolute darkest, games are a way of hurting others and being oblivious to the damage it’s doing to the player.

We play games for so many different reasons that the specific ones don’t really matter—we all just like to have fun. So we don’t spend all that much time picking apart why you play games. Who cares. You just do. You go on a games website and read something, and then you go about your day.

This is true of prisoners, too. They are, after all, just like us. They like to play games. Only some of them don’t have access to the Internet like we do. So they take pen to paper, write to their favorite games magazine, and send off largely boring missives to Sushi-X or whoever. Sushi-X doesn’t respond. But the prisoners keep on writing.

They’re just in another castle, and nobody really wants to listen to them.

Alejandro Quan-Madrid did. Or, at least, he wanted to write “a story that examined the plethora of convict mail [magazines] received as well as the larger narrative of ‘gaming behind bars,’” he explains in the zine’s page-long intro. Quan-Madrid, who also goes by “Aquma” or “Video Game Tupac,” heard about the letters from one of the then-handful of gaming podcasts in 2006. (Simpler times.) Alejandro befriended Shane Bettenhausen (now of Sony Computer Entertainment of America, then an editor at EGM) through a buddy of his who was interning under Shane; they started having AIM conversations about “hip-hop and other random things.”

Eventually, in 2007, Alejandro found himself in EGM’s office and he pitched Shane his story idea. EGM seemed “really into it,” so he was led into the mailroom. Jackpot.

“They were just pulling them out,” recalls Quan-Madrid. “They just gave them to me.”

As the zine explains, “The article didn’t come to fruition. This was thanks to my ambitious over-scheduling as an undergraduate and my inexperience with writing such a complex feature story on a subject I wanted to properly cover.”

Alejandro goes on to explain that he held onto the letters “because they tell stories.” The letters in the zine are provided without comment.

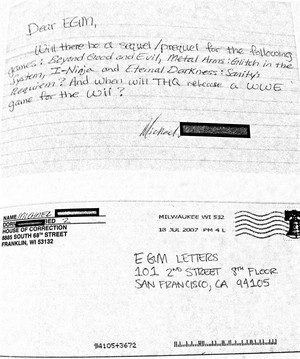

The prisoners’ letters are hauntingly mundane. Were it not for the scans of the envelopes on the outside, one would assume these are simple fan letters from enthusiastic children. They write in to inquire about whether their favorite series has a new sequel, or to point out how a review was inaccurate because “two of your reviewers called the creatures in God of War II ‘chimeras,’ but they’re griffins. Griffins don’t even have wings!”

Another reads: “EGM, I have a couple of questions for you guys. Hopefully you can provide me with some answers. First, what ever happened to game studios Grey Matter [sic], Ritual, and Human Head? I haven’t heard anything about them for sometime now. What are they currently working on? It would be nice to see something new from them. Especially Grey Matter (modern update for Kingpin would be cool).”

It goes on like this through the selection Alejandro curated for the zine: very simple requests for information.

These requests, as I’ve said, went unanswered.

Why?

More immediately, why hold onto these for years and years, put them in a zine, and then offer no additional commentary? When I talked with Alejandro, he explained that he “could have speculated, but it’s such a slippery slope, as far as coming up with your own analysis.” He thought “it might be better to present them in their purest form and let people read the letters and come up with their own stories … I don’t want it to be my interpretation of what these letters are about.”

But letters from prisoners to EGM asking whether there will be another Fester’s Quest doesn’t paint much of a story for me. I’ve taught sketch comedy, screenwriting, and improv; finding a story in a scrap of an idea is, literally, what I do. But I got nothin’ off these letters, and I’m willing to bet Alejandro didn’t either.

This is what’s confounding about them—why they lingered in Alejandro’s head, and linger in mine still. Their backstory is so alluring and haunting and their contents refuse to comply. There is no narrative here—just people.

“Honestly, we were often stunned by the sheer number of letters that EGM would receive from incarcerated gamers (and occasionally institutionalized ones, too),” explained Bettenhausen via email. “Perhaps they just had a tremendous amount of free time, and because most prisons didn’t actually allow inmates to play games…reading our magazine allowed them to stay abreast of the industry, and they could vicariously experience some of the new games by reading our previews and reviews.”

When I asked Alejandro whether he ever reached out to any of these people who wrote EGM in service of his story or in preparation for the zine, he explained via email that “being someone who is trying to make ends meet, I wasn’t in a position to invest that kind of emotional energy, time, and money (getting a P.O. Box, for example) into something that just had too many questions and variables. It’s almost like putting letters in bottles and letting them drift out to sea. It would be nice to do someday, but obviously the longer the wait, the less likely it’ll be the letters will find their intended recipients.”

Robert Ashley, who at the time was a “catch-all freelancer for all the Ziff Davis magazines until EGM shuttered in 2008” is, as far as I know, the only one from EGM who responded.

The only time Robert recalls interacting with one of the letter writers “was when someone doing time in some kind of light security place sent a letter about being stuck in one of the Zelda Oracle games for GBA. They were allowed to have a Gameboy, but this guy only had one game, and he’d been stuck on something for days. I thought that sounded like torture, so I printed out the entire Gamefaqs walkthrough for [the] game and sent it to him. Never heard back.”

Robert vaguely remembers scrawling a little note on the top sheet of the walkthrough: “Hope this helps!”

He says “the idea of having only one game to play in the world and being unable to progress in it sounded like pure hell.”

Limbo, not hell, may be a more appropriate descriptor. Bettenhausen recalled there actually was another contributor who “had amassed a large collection of [letters from prisoners]” who also hoped to compile them into “some sort of research project, possibly reaching out tot he original letters’ authors.” But, for whatever reason, “that didn’t quite come to pass” and Shane believes Alejandro ended up with some of these letters in his stash.

During our hour long chat, Alejandro touched momentarily on how the games industry doesn’t care about prisoners because “people in jail aren’t really consumers because they are stuck and don’t have the agency to buy games. If it’s an industry built around selling games, why would you cater to people who can’t buy them?”

Then, Alejandro mused: “I’m sure Game Informer probably still gets prison mail.”

This is a knowable thing. We have the Internet at our disposal, and long-standing editors at these publications all exist on Twitter or via email.

So I reached out to see whether Game Informer gets prison mail. I was curious.

Guess what: They do. Routinely. So does PC Gamer and Official Xbox Magazine. As did Nintendo Power and Official Dreamcast Magazine. It’s very likely that for as long as there have been game publications in print, inmates have taken pen to paper and produced very staid letters about games.

Justin Cheng, my editor at the now-defunct Nintendo Power, wrote that they “got lots of letters from prison inmates. We never responded to any of them, I don’t think; maybe we did once or twice in the letters column, but I’m not sure. As for what they wrote about … I think they were mostly asking questions about upcoming games or mentioning something they liked about the magazine. I don’t remember there being any odd letters from inmates. (We did get weird letters from other readers, though!)”

Game Informer’s Matthew Helgeson, the mag’s senior features editor, wrote, “Years ago, I remember getting a few via US mail… handwritten letters, only recall a couple and don’t remember what we did with them, if anything.”

Evan Lahti, PC Gamer’s editor-in-chief, offered this:

We do. We definitely do, approx. once a month. Juvenile centers are probably about half of them. The content of the letters honestly doesn’t differ—there’s almost always nothing personal in letters from inmates, just earnest inquiries about hardware and which components we’d recommend.

Their handwriting is almost universally amazing.

My guess is that they feel like they’re more likely to get a response if they omit that stuff, or that we wouldn’t care? (Which isn’t true.)

When I asked Evan if anyone from PC Gamer ever responds to the prisoners, he wrote:

We respond to as many as we can. I wish we could write everyone back.

That’s sort of the thing here.

It’s tempting to lump prisoners together as one group of people, but that’s just because society has done that.

The truth is they’re no different than any of us on the outside—just a big blob of humanity wondering whether there’s gonna be another Fester’s Quest.

According to a 2012 piece in British national morning newspaper The Independent, some “36,000 inmates are allowed to play video games in prison.” Granted, this is only applicable for prisoners “under a good behaviour scheme.”

It’s tempting to paint everyone in prison as a violent criminal. As vicious rapists. As maniacal rapists. But, as Alejandro asserts in his zine: “I assume [these people] to be decent folks, who also love my favorite medium but who made a poor decision in life. We don’t know their circumstances.”

Consider this recent February piece in Kotaku about Anders Behring Brevik, who killed 77 people in Norway in 2011. Evan Narcisse, the piece’s author, writes that “since [Brevik] said that he used Call of Duty to practice his aiming and World of Warcraft to hide his plans, video games have been became [sic] part of the story of his horrific crime. Now, 18 months into a 21-year prison sentence, he’s demanding that his PS2 be upgraded to a PS3.”

Narcisse reports on prison letters to authorities from Brevik, where he gripes that “other inmates have access to adult games while I only have the right to play less interesting kids games. One example is Rayman Revolution, a game aimed at three-year-olds.”

Rewind back a bit further to 2006. USA Today ran a piece on Oregon inmates playing games. It explains how one of the prison system’s “most prolific troublemakers” is staying out of trouble thanks to videogames. And not a non-violent game, either, but “intergalactic war game Star Ally.” (I’ve never heard of it, either.) The article explains the inmate in question has “been free of trouble for almost two years, thanks in part to the video games he gets to play at the Two Rivers Correctional Institution in Umatilla, where the 23-year-old is serving nine years for assault, attempted escape and other crimes.”

Prisoners play games. How play might liberate or counteract or reinforce a life of confinement is probably for those prisoners to dissect. Not us. From the outside, what we hear—me, Alejandro, Robert, Shane, and now you—is a voice completely disconnected from that experience. They’re asking for information, but they’re asking moreover to be heard.

I started writing this piece looking for closure, looking for some way to hear those voices. I doubt I’ll get it. I pulled a thread to see where it lead. Now I’m here.

For my part, I have been using it to talk further with Alejandro and Robert about trying to track down some of these prisoners. All the three of us have is Alejandro’s stack. There’s a Google Doc spreadsheet shared between us with names and prison addresses. I poked around for a while and couldn’t find much. None of them have distinct enough names to yield results quickly.

But that doesn’t mean we can’t still look. Somewhere, somebody sent these.

///

Editorial assistance by Kyle Kukshtel