This article was produced in partnership with Intel iQ.

Function has always been limited by form. We want the best, but we want the best to also look appealing. Air Jordan sneakers cost two hundred dollars not because of their arch support, but because people want to wear them: or, rather, to be seen wearing them. They are desirable. It’s the same reason Cherolet’s Corvette outsells the Chevy Volt, gas mileage be damned. We want the benefits of advanced technology without sacrificing our aesthetic sensibilities, shallow and counterintuitive though they may be.

The coming wearable revolution thrusts computers onto the same battlefield as watches and eyewear. But we’ve been here before. Game companies, so often devoted to simple joysticks or plastic buttons, have tread these same wearable waters, experimenting with classic failures such as the Power Glove or SegaScope 3D Glasses: both attempted an immersive experience beyond what was previously available; both simply made the user look ridiculous. Few peripheral controllers succeed—an exception brought on by the music game explosion, with its fake guitars an acceptable middleground between kitsch and style—and we can’t help but wonder if the same phenomenon is at play. Will there ever be a gaming peripheral that is as desirable to wear and use as it is to play?

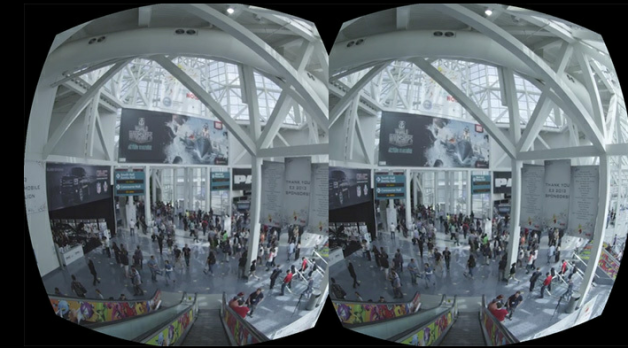

Danfung Dennis hopes so. The Oscar-nominated filmmaker’s new documentary Zero Point explores the past and future of virtual reality. His project exemplifies the present: Zero Point is filmed exclusively for the Oculus Rift. “[VR] is this new visual language,” Dennis says,”[and].we need to invent the syntax and the grammar for how to effectively communicate a narrative … when you have no control over where the user could be looking.” What is often ignored in this equation is the device the user is controlling. Because if virtual stories are to be watched, or games played, we will need a headset that the average person will actually put on their face.

“For [wearables] to be really successful,” Paola Antonelli, senior director of the Museum of Moden Art’s Architecture and Design department, told me, “they would need to not exist.” This paradox is the great obstacle to wearable computers, the untenable overlap between form and function: Nobody wants to be told what to wear. “I don’t want Google or Nike or anybody else to decide what kind of bracelet or eyeglasses I need, “Antonelli said. “I want to apply their technology… to whatever I decide to apply it to. That to me is real freedom of expression.”

Even in the face of outstanding gains, the limitations of a single, oft-ugly form factor threatens the mass acceptance of even the most useful new gadget. When asked how upcoming devices could improve upon the sterility of a single choice, she references a surprising product: Swatch, the Swiss company that revolutionized wristwear in the 1980s with their wide variety of cheeky, colorful watches. All watches tell the same time. But Swatch let you do it your way.

Perhaps it was this same problem that plagued early game peripherals. Might a Power Glove in five different colors have been more successful? Maybe not. But the designers of the future should heed Antonelli’s words. The Rift is one VR headset shooting for mainstream acceptance among a rising tide of competitors, from little-known Avegant to giants like Sony and Microsoft. But they all face a wall of societal stigma; the cyborgian future many thought would be the norm by now just has not come to pass. Even Google Glass, the high-water mark for advanced wearables that connect a user with their endless data stream, has gone from a Silicon Valley status symbol to being ripe for parody, or, worse, an unwarranted catalyst for abuse.

Sherry Turkle’s triptych of books (1984’s The Second Self, 1995’s Life on the Screen, and 2011’s Alone Together) has plotted our gradual ascent into the virtual ether. Her ultimate concern is that all this technology isolates more than connects us. “Today, our machine dream is to be never alone but always in control,” she writes in Alone Together. “This can’t happen when one is face-to-face with a person.” Nor can it happen without a way to embody ourselves in the very products we wear. And only we get to choose who we wish to be.

“Even Oculus, which is fantastic, is still something you need to wear on your head,” Antonelli said. “When you are forced to wear something, that’s an impingement on your freedom to choose what to wear.” And the more technology dictates how we view and interact with the world around us, the more these items need to reflect the wearers. Antonelli reminded me this is not a new problem.

“Wearable technology has existed for centuries,” she said. “Watches are wearable technology. The technology has changed, but we’ve been wearing it for a long time.” Even game controllers, which began in the arcade as a custom set of inputs for each unique game, have been boiled down into a standard, expected pad, largely identical across the three major systems. Antonelli, as a museum curator, and thus dedicated to finding the ideal within a wide range of possibilities, knows this portends a problem.

“Standardization doesn’t work that well when it comes to things you want to wear… Just [look] at the need human beings have for variety and self-expression through what they wear,” she said. “We can learn a lot from the past.” Even when we’re trying to build the future.