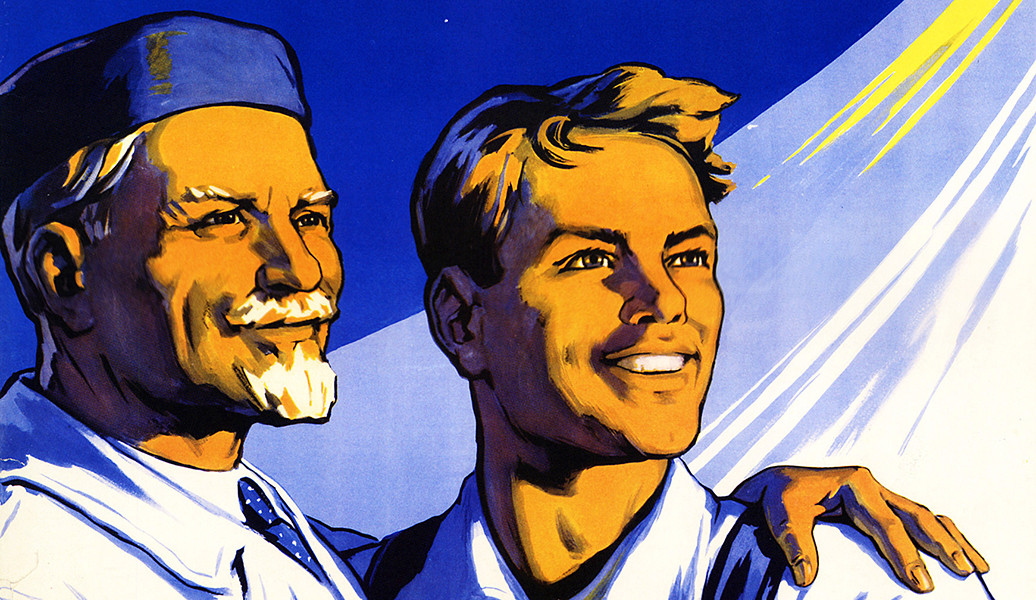

This article shares the first part of its title with the tagline for this iconic 1920s Soviet propaganda poster. Also considered were the taglines for this poster, issued during the space race, which reads “I am happy—this is my work joining the work of my republic,” and this one’s, “Glory to the workers of Soviet science and technology!”

All of those harmonious lines and primary colors is an attempt to transcend the simple notion of work as subsistence. Work, we understand, is inherently glorious. The labor of the field worker is no less important, actually indistinguishable, from the labor of the privileged or elite scientist. To work, at least in the blinkered and simplistic worlds portrayed in very old propaganda posters, is to exceed not only the drudgery and banality of the experience of carrying out work, but one’s limitations as an individual. Work is the defense of homeland; conquering the stars; progressing the very species (or at least its Soviet subsection).

But it’s not enough for work to be metaphysically good. These posters also propose that work feels good, regardless of who is doing it, or in what context. Of course, the fact that they have to make the argument feel good acknowledges that the individual needs convincing—that their experience of work says otherwise.

In places like the Soviet Union, where the Biblio-metaphoric quality of “daily bread” was actively hollowed out by Communism, propaganda posters performed an aesthetic reframing of work to render its notion inspiring—to imbue it with the Union’s own divine influence (of the party), noble intention (of the worker), and perpetual meaningfulness (of the collective). But the clumsy smashing-together—or attempt at smashing together—of the experience of working and the vision of work’s outcome is not exclusive to collective thinking. Studs Terkel, in his classic of oral American history, Working: People Talk About What They Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do (1974), wrote that work was a search, sometimes successful, sometimes not, for daily meaning as well as daily bread.

In the America of Terkel’s Working there is a patina of existentialist anxiety; the reader is often tempted to throw the book against some very distant wall by the excruciatingly detailed accounts of working people’s daily lives, the minutia of the day-in-and-day-out experience of, Work-As and thus Life-As, a waitress, a toll booth attendant, a construction worker, a lawyer, a doctor, and so on. Across professions, blue- and white-collar, the reader is driven to ask, again and again, in an echo of what many of these same workers out-and-out said to Turkel: “why am I doing this?” In the absence of Soviet-style propaganda, which presumes to provide the answer to that question, Working presents workers in various states of alienation, from some to total. The attitude is different, but the underlying question of what work means remains.

It’s against the incongruity of the experience of work and the (projected or real or nonexistent) meaning of work that we then tend, in a binary way, to define “play.” Play can be understood as a temporary escape from the irreconcilable desires for meaning and the often meaningless nature of the work in which we engage every day. Play doesn’t necessarily fill the void of meaning left by the lived experience of work. But it is certainly more entertaining in that it involves some element of choice, that its sensations dull the ache to feel that we are accomplishing something.

This work/play dynamic feels too binary, premised as it is on a presumption that work and play are mutually exclusive—work does not permit play, and play does not feel like work. But something strange has occurred in videogames: our play, the kind of play exemplified by certain types of games, can be satisfying because it mirrors the routines of work, and specifically the sensation of endless repetition without context. Work and play are the flip sides of the coin of our daily lives.

“Metroidvania” (or “Castleroid”) games are a genre of non-linear platformer exemplified, as you might have guessed, by the Metroid and Castlevania series, both of which debuted in 1986. I recently replayed my way through the two best entries in each franchise—Super Metroid (1994) and Castlevania: Symphony of the Night (1997)—and found myself thinking that their greatest accomplishment was not achieving the temporary avoidance of the feeling of doing work—as one might expect from the best entertainment, and certainly from two of the greatest videogames of all time—but that they distilled so effectively the satisfaction one feels when they do work and do work well.

They do this by developing a perfect balance of accessibility and challenge that continuously rewards the player for having carried out work, but more importantly, they introduce the sensation of repetition and unendingness to the platformer formula. Some classic 2D platformers insist on inexorable forward progression from left to right, sometimes even forcing it with an uncompromising scroll or timer. (Various Mario Bros. games do both of these things, as do nostalgic platformers like Kirby and Donkey Kong Country., which use these methods as shorthand for a style of play as opposed to technical limitations.) But in Metroidvania games your character is free to explore not only rightward and upward and downward, but—shockingly!—leftward, which is to say, over ground already trod. This introduces a form of repetition we might be most familiar with from work.

This seems like a tacit admission that sometimes you need to do over what you’ve already done and try to do it better, or try to do what you’ve done again as a newer, more mature, more able version of yourself, in order to achieve a goal. It’s also an excellent way to make a game feel enormous without having to design an enormous amount of new game environment. In that way, Metroidvania games don’t just successfully mimic the self-legitimizing experience of work for work’s sake; they were also a capitalistic breakthrough in efficient design, similar in spirit to old-school cartoons, which cycled the same background animation cels over and over to give the sensation of motion.

Generally, what’s prevailed about Metroidvania games is the emphasis placed on the incremental unlocking of progress through non-linear exploration and the collection of specific skills, objects, or MacGuffins. Sometimes this has some tangential relation to internal logic—say, “you need to find the key before you can open the door.” (Said key is naturally found in the same castle in which the door is located; this doesn’t strain one’s credulity. The important difference between Metroidvania and traditional platformer games is that the location of the key may be past the location of the door, as opposed to before it, requiring backtracking.) Sometimes this logic is slightly more obscured—“there’s an orb in this castle that allows vampires to transform into mist, which allows you to pass through that grate.” (Even if one presumes vampire-specific approaches to home security, one whose analogues to keys and doors is magic mist-orbs and grates, the games rarely go so far as to establish this via narrative. One is left to plug these gaps in lore by oneself.) Castlevania: SOTN places even greater emphasis on this type incrementalism and repetition than Super Metroid, because it introduces JRPG-style grinding to the mix: you level up through combat, which increases your health, strength, etcetera.

The key difference here between JRPGs and Metroidvania games is that while JRPGs also simulate work, their designers seem disinterested in disguising that work’s arbitrariness. The player is launched by indifferent systems into encounter after encounter against creatures without motivation or even a casual relationship to the game’s antagonists. Accumulation is not only a requirement to advancement, it is also often the central game experience. The player chips away at their mountain of work to watch numbers climb in character profiles. Metroidvania games, on the other hand, strike a balance in gameplay that is almost insidious in its subtlely. You barely perceive the repetition; the experience of both Super Metroid and Castlevania: SOTN, though I had not played either in several years, was instantly familiar and as comfortable as a well-worn glove. I was able, in only a couple of minutes, to find the playing groove, rhythmic and ever-moving, with few narrative interruptions to my sensation of continuous progress.

Work is most frustrating when it’s performed without context—which is to say, when you don’t know why you’re doing it. And Metroidvania games, while classics because they avoid this frustration most frequently, are not exempt from frequent absurdity. After all, Metroidvania games were developed at a time when the gaming industry put less emphasis on drawn-out, Hollywood-style storytelling, many of which stories explicitly ask the individual to consider the consequences of their actions. Like Soviet-era propaganda, reflection in Metroidvania is kept to a bare minimum.

In Castlevania: SOTN, after a brief prologue, you’re dumped into the game as Alucard, the half-human, half-vampire son of Dracula. Your maternal heritage, or motivation for hunting your dad, or even why Dracula decided to have a child with a human woman as opposed to his classic and well-established approach to reproduction, is never explored in any depth. (Do vampires sometimes have babies? When they bite you and you turn into a vampire, is the vampire who bit you considered your dad? Was the relationship between Alucard’s mom and Dracula, the incarnation of evil, consensual, passionate even? At one point in the game Alucard is confronted by a vision of his mother, which turns out to be a succubus, a demon who takes the form of a woman in order to seduce men. Do vampire boys suffer from the same Oedipus complex as do some human boys? What seems ripe for exploration is left hanging, or I suppose you could say flaccid.)

No matter: Dracula’s castle has risen, and so the game must simply be. (Which, again: the castle has risen? Is Dracula the antagonist here, or merely the toughest among supernatural ghouls mindlessly tracing out preset patterns, the avatars of an evil force who is also responsible for the presence of a castle? Or does Dracula’s presence ensure the architectural integrity of his castle the same way Sauron’s does his eye-tower thing in Lord of the Rings?) Expository prose, if it can even be called that, is wooden, perfunctory in nature, and possibly the result of poor translation. Consider the following exchange between Alucard and a creature known as the Master Librarian:

Alucard: It’s been a long time, old one.

Librarian: Oh! Its you, master Alucard. What do you need?

Alucard: I need your help.

Librarian: Young master, I cannot aid one who opposes the Master!

Alucard: You won’t go unrewarded.

Librarian: Really? In that case, just tell me what you need.

Super Metroid fares somewhat better by removing dialogue almost entirely. Though later entries in the Metroid series attempted to expand on the backstory, Super Metroid simply offers that Samus Aran has discovered the continued existence of space pirates, that they’ve retaken the metroids from peaceful scientists who were attempting to use them for the good of “civilization,” and she’s off to the races. Little justification is offered for the hours of work the individual is about to engage in. The primary focus, we understand, is on the physical tasks at hand.

Once the game begins you not only progress through one area doing work, e.g. killing bats or space bats, but you are then forced to bypass as-yet unopenable doors, knowing you will have to fight your way back through regenerating bats to open that door at some later time. This is no better signified than when you accidentally step off-screen after a hard-fought battle, then turn around and re-enter an area only to find your enemies instantly re-spawned and mindlessly spitting fireballs into space. Your work is continuously undone, never-ending. This repetition is also enforce through one’s reliance on save-points: physical locations in the game that the player must discover in order to save one’s progress. Failing to do so often results in having to replay whole sequences of exploration because one couldn’t find a save point or a life-saving hunk of pork hidden, naturally, in a candle before receiving the fatal blow. In both cases, the player is faced with the same Sisyphean paradox underlying both the Protestant work ethic or the Soviet compact: the worker will find salvation through the completion of work / the worker’s work is never done.

To play through classic Metroidvania games is to struggle with the notion that enjoyment of these games may be a byproduct of having been raised in a culture that privileges accumulation through work. Videogames, and particularly Metroidvania games, are the manifestation of this dynamic at its most polemic—repetitive, ritualized, stylized work, without the reward of even internal logic.

Another premise of Metroidvania games is that you begin with all of your powers. The game presents you in your natural state: dominant, lightning quick, hyperpowerful; you mow through some preliminary enemies as if they’re nothing. In both Super Metroid and Castlevania: SOTN, your character completes the ultimate chapter of a preceding narrative—annihilating Mother Brain or Dracula—giving the impression of higher stakes to follow. You’re teased with a linear opening too easy to fail. Then you’re robbed of it all—reduced to a slower, weaker version of yourself. Samus and Alucard encounter some kind of early deus ex machina in their respective games which has the power to deplete you, the player, to almost nothing. (In Alucard’s case he encounters Death himself, leading one to wonder how, should Dracula have Death in his employ, he has failed so many times against the Belmonts and their exotic collection of whips.) Ledges heretofore accessible are suddenly, achingly, not accessible. You can no longer roll up into a little ball and squeeze though a crack in a wall into that tantalizingly visible room that signifies Some Larger and More Exciting Part of the World.

It’s a bit like watching a car commercial—a richer, more handsome version of somebody, one hand on the leather-coated steering wheel, guiding a luxury performance vehicle down some unspecified coastline so that you know what success looks like, the fully powered up Samus Aran or Alucard of late-capitalist fantasy, powerful enough to direct the ebbs and flows of the world around them. That these games’ narratives, malnourished though they are, always place progress in a moralistic framework is equally problematic. The very world depends on the player enacting a consumerist cycle of work and accumulation.

Metroidvania games consciously or unconsciously reproduce the mindless automation of industrialized work, acclimatize us to its dehumanizing sensations, make us susceptible to its meager rewards. But I urge you: go ahead, enjoy these games. I do. Is that enjoyment not real, or legitimate? Both the enjoyment and root cause of that enjoyment are important and worth thinking about.

Corey Robin, in his essay on Nietzsche and the Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek, wrote “The Greeks […] saw work as a disgrace,” because the existence it serves—the finite life that each of us lives—“has no inherent value.” Existence can be redeemed only by art, but art too is premised on work. It is made, and its maker depends on the labor of others […] No matter how beautiful, art cannot escape the pall of its creation. It arouses shame, for in shame “there lurks the unconscious recognition that these conditions” of work “are required for the actual goal” of art to be achieved. For that reason, the Greeks properly kept labor and the laborer hidden from view.” Gaming, too, is an intersection of art/play and work that seems to unwittingly reveal the nature of each, negotiating around the edges of work and play’s paradoxical irreconcilability and interdependence.

The central dilemma of gaming, then—or, what modern games can learn from Metroidvania games—is not to achieve some ideal form of pure entertainment that escapes the banality of work, or to accomplish anything more meaningful than the conversion of one collection of colored sprites on the screen into another collection of colored sprites. It is that, in the context of their meaninglessness, these games should achieve a satisfying balance of accessibility and challenge that is interesting from a technical standpoint, but is also only made possible by the framework of production and consumption a player brings with him or her to the game: art in that they interrogate work, and yet satisfying to play because we recognize the work required to play the game. A “good” game can be determined either by the way it uses this socialization to its advantage or disrupts it, depending on what it wants to accomplish.

Super Metroid and Castlevania: SOTN are masterpieces not because they transcend the feeling of work, but because they use our familiarity with the feeling of work to make the experience of playing them effortless. They distill that which often makes work satisfying: the sensation of accomplishment and ability, doled out in reasonable increments and at an artful pace that is often invisible to the worker. Modern gaming struggles to pioneer moral conundrums and bold new aesthetic designs; it seems disinterested, at the moment, in achieving what Metroidvania games achieved. The classics of Metroidvania treat work as sublime, as a means and an end. “I am happy.”