Profile: Craig Adams

To put it mildly, the hype machine has shown nonstop love for the upcoming Superbrothers production Sword & Sworcery EP. I played through a fair bit of a mature beta, and it is every bit the smartly crafted affair I had hoped for. Sword & Sworcery feels like a game created by one of us. Among those who desperately try to convince non-gamers that Super Meat Boy is a feat of engineering genius, or that Metroid Prime can go toe-to-toe with many of the great narratives of the past 50 years, someone has quit talking and decided to just create something beautiful. Sworcery isn’t grandiose—but the sneaking suspicion is that it may be our “one small step for games” moment.

“It’d be great for people to pick up this game and realize that a videogame can be a pleasant conversation.”

At the heart of Superbrothers is Craig Adams, a Toronto-based artist and game designer who decided one day in 2008 to leave an unfulfilling job at Koei to make a game. “Superbrothers made sense, because now is the right time for small teams to do great things, and I had a game experience in mind.” A journey into the study of pixel art and a failed attempt at animation led to mixtape swaps with music legend Jim Guthrie and booze-fueled powwows with Capybara Games. Adams helms the Superbrothers project with musical input from Guthrie and development from Capybara. They may ultimately have begun one of the most articulate ruminations on games in the past decade.

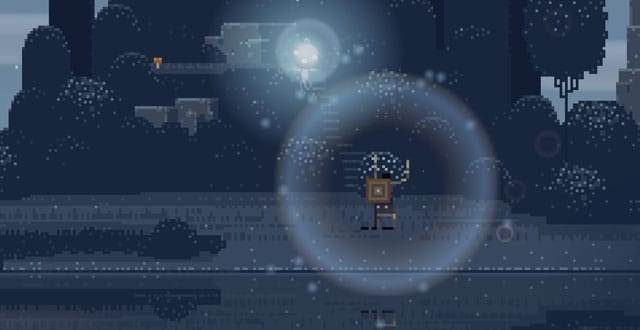

On the surface, Sword & Sworcery EP is an adventure story about a warrior journeying into unknown territories, fighting wolves, monsters, and gods while unlocking the mysteries of a sacred tome. The fluid and intuitive touch controls encourage exploration and experimentation. But these are just the beginning of a dialogue between player and game about interaction, music, and sharing (there’s also a bit of Twitter involved).

“For me, it was never going to be anything but games. But it took me a while to get there.”

Adams is a gamer through and through, having watched his siblings play on the Commodore 64 and VIC-20. The Adams kids would borrow stacks of pirated, unmarked diskettes and search for new game experiences on each one. He was hooked from day one:

“There was this kind of archeological aspect of taking each diskette, putting it in and looking for a game file, and then booting it up. You don’t know what the game is, what the concept is; but you just press buttons and try and figure it out. I really treasure that experience to this day.”

This relationship between device and user is a driving force behind much of the gameplay Adams has designed. He likens the game experience to learning a new language, which boils down to a direct conversation between gamer and game developer: You do this, and that is what will happen in the game.

Many of us have become accustomed to gaming languages, and even take them for granted in certain genres. Down, Right, Fierce will never fail you in a 2D fighter. What separates great games from the chaff, in Adams’ view, is the craft and depth of their language.

“We’re developing some specific form of videogame language, and we’re trying to speak it in a specific way.”

For Adams, this is more than user actions moving avatars on the screen. It’s a form of discovery. We learn the rules of a game’s world—its visual, aural, and actionable laws. If I fall down the pit, I die. But if I take the pipe, I go to another world. These mechanics are to videogames what words, sentences, and punctuation are to writing.

Any game can be a fun platformer, but when we look at the depth and richness of Super Mario Bros.’ conversations with the gamer, Adams sees something remarkable.

“Coins are a perfect choice for a collectible item, the way they hover in the air, twirling and twinkling; and they are so satisfying to obtain when you hear that sound. This is all a product of design. It could have been anything hovering up there.”

No one can argue that Nintendo doesn’t make great games—but even fantastically made toys are still toys. No one ever looks to Mario, Zelda, or Kirby for reflections on human truths. In a sense, Miyamoto and company are artisanal masters, the best landscape painters of their era. The team at Superbrothers delves a little deeper into what “games” mean to us.

At art school in 2002, Adams started hanging out with the pixel-art illustrators and designers who were pushing abstracted game art in new directions. He returned to Eric Chahi’s classic Out of This World, which he first played in 1993:

“It was striking a totally different tone. It was awkward and frustrating at first. But then, as you got into the swing of it—the way that it looked and it moved—it was something else.”

The influence of Chahi, along with Jordan Mechner of Prince of Persia fame, is all over Sword & Sworcery. Adams covets the narrative qualities that their games attain through abstraction and simplification. Mechner’s Prince isn’t captivating because of lifelike details. Climbing up a ledge is depicted with a few short sprites; and yet, each one feels properly weighted in time. There are no wasted frames or excessive motions—just an appropriate response in the game’s world to an action from our keyboard.

Scott McCloud’s groundbreaking work Understanding Comics devotes a whole chapter to the idea of reduction, and Adams refers to him when discussing abstraction: “McCloud talks about how the simpler an image gets, while retaining the most information, the more universal it becomes. So instead of a detailed face, we get a simple smiley face that everyone can relate to.” In videogames, we can apply this idea not only to visuals, but also to motion, sound, and action.

“I came up with this nonsense buzzword of I/O Cinema, but it does capture what I’m interested in.”

Adams hopes to build a distinct videogame language for himself and his team that engages his players in that input/output experience he discovered as a child. He isn’t concerned with nostalgia, but with whether the conversation between player and developer can happen: “We’re developing some specific form of videogame language, and we’re trying to speak it in a specific way.”

Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery EP is released “around the vernal equinox” on iPad, and subsequently on iPhone.

Errata: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated Craig Adams’ position at Koei and the release date of the game. These have been corrected.