Psychedelia isn’t dead, just ask videogames

Though it hit peak popularity in the 1960s, psychedelia has endured as a genre of art, film, and particularly music that occasionally goes through periods of resurgence. Some of the best current examples of psychedelic culture, however, come from a medium that barely existed in the 1960s: videogames.

You can find dozens of lists of the best “psychedelic” videogames, but many of these lists focus on the superficial aspects of psychedelia. They use “psychedelic” as a synonym for “weird,” ignoring the original meaning of the word. Influenced both by early 20th-century abstract art and by experiments with hallucinogenic drugs, the first psychedelic artists wanted above all to explore and expand minds (with “psychedelic” being derived from the Greek words for “mind” and “to reveal”). While tie-dye colors and druggy imagery are the most visible hallmarks of psychedelia, the goals of most psychedelic artists extended beyond simply recreating the experience of being on drugs. LSD and other hallucinogens played a key role in psychedelia, but rather than being the end goal, they were a tool to reach states of transcendence and interconnectedness that weren’t possible to reach with the unaltered mind. Some artists saw the mind exploration of psychedelia as a spiritual quest and took inspiration from religion—particularly the religions of India, where concepts like prajñā (the wisdom to see the world as it really is) were repurposed to fit with a psychedelic lifestyle.

They were a tool to reach states of transcendence and interconnectedness

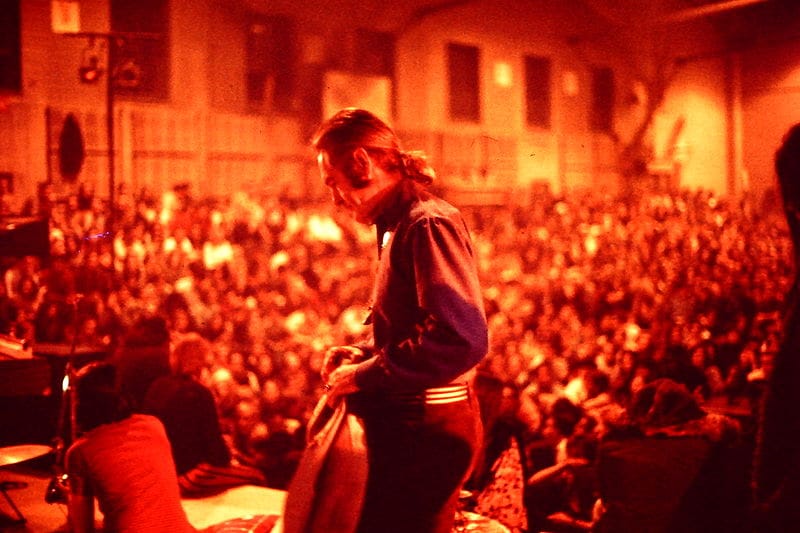

The most popular form of psychedelic art, psychedelic music, peaked in the mid-1960s and began to taper off shortly after LSD was made illegal in 1968. But while psychedelic music’s reign in the mainstream was short, its influence remains. Original psychedelic bands like the Grateful Dead and Pink Floyd have maintained cult followings into the present. More recent musicians like The Flaming Lips, Primal Scream, Tame Impala, Animal Collective, and Ariel Pink draw influence from the first psychedelic bands while also expanding the genre with synthesized instruments and digital recording techniques that didn’t exist in the 1960s. All of these bands have defined not only the sound of psychedelia but also the look of it, by including psychedelic imagery in their album covers, live shows, and music videos. LSD users often report feelings of synesthesia—when the body’s senses run together so you can, for example, “see music” or “smell color”—and psychedelic musicians frequently aim to recreate this experience with a sensory overload of sound and visuals.

New technology like video streaming and Pro Tools has helped modern psychedelic bands make even more immersive synesthetic experiences. Some artists, however, have gone a step further and incorporated a new element into their psychedelic journeys—interactivity. Browse the psychedelic tag on an online videogame store like Steam or itch.io, and you’ll find dozens of neon-colored banners for games that promise all sorts of mind-bending journeys and general trippiness. Some of these games simply use the visual style of psychedelia as window dressing, but others could be direct descendents of the original psychedelic art, sharing the same quasi-spiritual goal to free the mind by exploring it. Consider Sluggish Morss, a glitchy, sci-fi claymation series of games that could easily provide the imagery for a Flaming Lips music video. Or there’s Trip (2015), a peaceful game about exploring abstract art that, like the Grateful Dead, encompasses every possible meaning of the word “trip.” These games do more than just adopt the visual style of psychedelic music—they use its aesthetic as the basis for an introspective journey that simulates the experience of having an altered mind.

Many of these titles come from the more obscure fringes of game design. Some of the creators even avoid the word “game” in their descriptions—Sluggish Morss: Ad Infinitum (2014) bills itself as a “game/interactive music clip/album about space” while Trip’s tagline calls it an “experience.” But psychedelia has also begun to influence more traditional games—especially the types of independent titles that regularly reach the top of online bestseller lists.

psychedelia has also begun to influence more traditional games

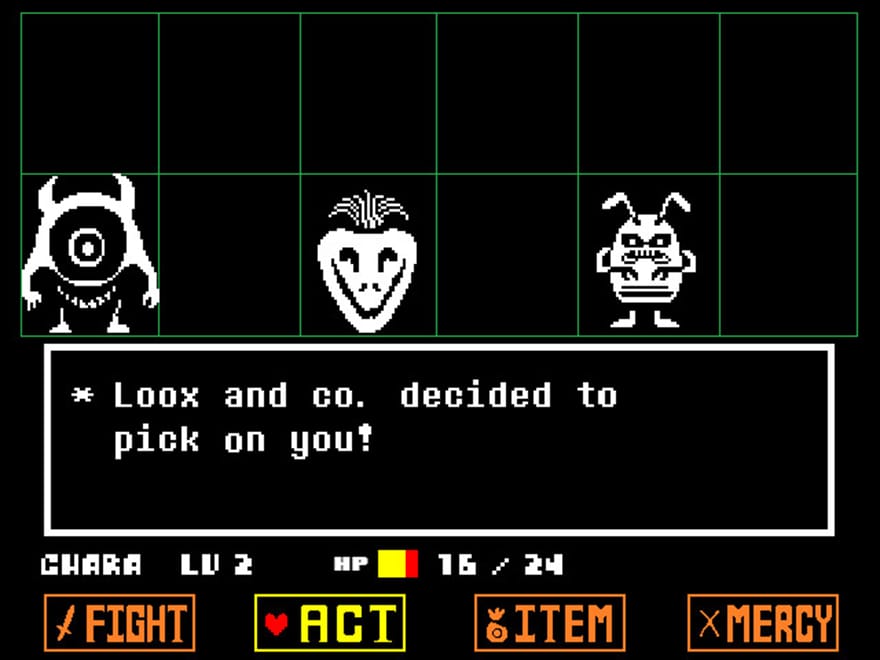

Undertale (2015), whose central hook is that you can peacefully resolve conflicts with monsters instead of fighting them, clearly echoes the pacifistic hippie dreams of the 60s, but it also embodies other aspects of psychedelia. While Undertale might appear at first to be a game with a linear story, players who reach the end learn that the story is cyclic: choices you make during your first time playing will affect what happens when you replay the game. In many ways, the game’s structure embodies the ideas of birth, death, and rebirth that are central to Indian religions—and by extension to psychedelic music, which is full of songs like “Tomorrow Never Knows” by the Beatles and “The End” by The Doors that draw influence from Eastern spirituality. By dramatizing the effects of your choices from past “lives” and by trapping the player in a loop of death and rebirth, the game creates a state of samsara—the cycle of life from which spiritual-minded LSD users sought to escape. And whether or not it’s intentional, it’s fitting that the only way to escape samsara and achieve “nirvana” in Undertale is to totally let go—to stop playing the game.

Another feature of both psychedelic music and many recent independent games are surreal experiences with animals. Syd Barrett sang, “That cat’s something I can’t explain” on “Lucifer Sam,” and inexplicable animals have been a staple of psychedelic music from Jefferson Airplane (“White Rabbit”) to Tame Impala (“Elephant”). Weird animals have also long been featured in videogames—just look at Sonic the Hedgehog or Crash Bandicoot—but recent games have given this weirdness a psychedelic spin. After all, if there’s a logical modern-day successor to the Beatles’ “Octopus’s Garden,” surely it’s Octodad: Dadliest Catch (2014), a game about a loving father who performs household chores and is also secretly an octopus. Attempting to control the eponymous Octodad, who moves around his house like Hunter S. Thompson on ether, is a trip in itself.

Psychedelic animal games with intentionally dodgy controls have become something of a microgenre, with Catlateral Damage (2013)—a game about a kitten bent on destruction—and Goat Simulator (2014), being two other popular recent examples. These games follow a sort of dream logic where players are rewarded for, say, bouncing a bicycling goat off a trampoline. It makes no sense, but then again, neither did “Goo goo ga joob.” Psychedelic music’s obsession with animals came partly from Lewis Carroll, who loved hiding mathematical jokes in his work, and you could argue that the physics engines in these games, which are designed to produce maximum chaos, are equally elaborate mathematical jokes. These games force players to follow their own internal logic—which differs considerably from real-world logic—leading to a surreal experience that’s similar to the sensory confusion of synesthesia.

The focus on animals is a natural counterpart to one of the other major themes of psychedelia: the longing for a pastoral lifestyle. Psychedelic albums like the Kinks’ Village Green Preservation Society or Lindisfarne’s Fog on the Tyne depicted idyllic natural scenes as an antidote for urban, industrialized life, and a crop of recent independent games have done something similar. Firewatch, for example, is something of a paradox: a videogame that wants you to go outside and explore. It’s the story of a man who tries to escape his daily life by taking a job as a fire warden at a remote forest outpost. The game juxtaposes scenes of emotional turmoil with beautiful, hyperrealistic images of nature. In that respect, Firewatch is the videogame equivalent to a song like “Waterloo Sunset” or “Fog on the Tyne.” Flower (2009), a relaxing game about flower petals blowing in the wind, was arguably the first idyllic nature videogame to gain widespread acclaim, although the subgenre has roots in farming simulators like Harvest Moon (1997) and its modern counterpart, Stardew Valley. These games lack the mind-bending imagery of most psychedelia, but they share psychedelia’s yearning to withdraw from society and become more introspective.

Many of these games might seem weird for the sake of being weird, but psychedelic games often share a similar, purposeful goal. Timothy Leary, the famous LSD evangelist, wrote about “ego death”—a way to transcend the self. Few, if any, of the creators of these games are advocates for psychedelic drugs, but these games do aim for something similar to Timothy Leary’s ego death. They all force the player to consider things outside of their own experience. Psychedelia doesn’t have to be deep: sometimes it’s silly (“Dude, what if my arms were tentacles?”), and sometimes it’s nothing more than idle stoner philosophizing. But the best psychedelic games use their weirdness as a tool to promote empathy, encouraging players to think selflessly when it comes to other people, animals, and nature. The medium has changed, but the desire to explore the mind remains same.