Quantum Break is better TV than videogame

In Remedy Entertainment’s Max Payne (2001) and Alan Wake (2010), the player can approach television sets and watch short, surprisingly detailed videos. In Max Payne, these include soapy melodrama Lords and Ladies and the paranoiac, Lynch-riffing Address Unknown. Alan Wake sticks to a Twilight Zone-inspired anthology series called Night Springs. These TV shows are worth mentioning as a reminder that Remedy has never been shy about recognizing its influences. As such, Max Payne is a blend of Hong Kong cinema gunplay and conspiracy-laden noir. While Alan Wake is a Stephen King thriller filtered through the lens of Twin Peaks and The Twilight Zone. Both games are played straight—they intentionally lean into the campier side of their inspirations without ever attempting to mock them. The in-game televisions are a loving acknowledgement of the stories the developer enjoys and a clear signal to the audience that the story they’re watching is an intentional send-up of established genres.

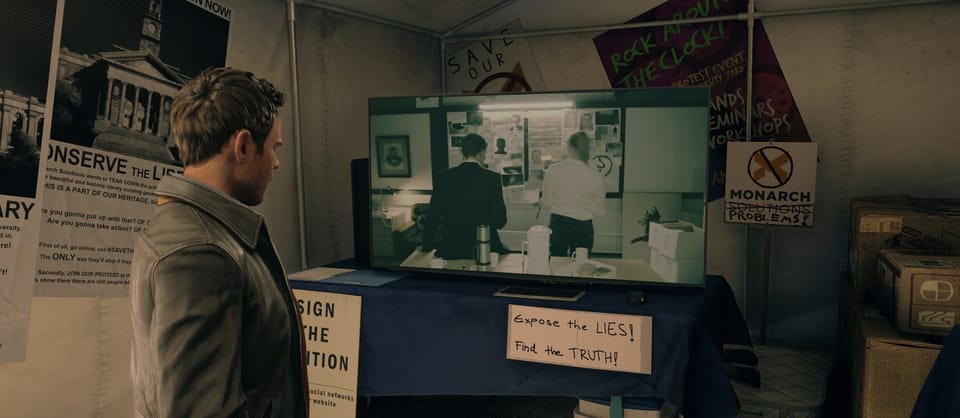

In Quantum Break, Remedy’s most recent work, the player can guide protagonist Jack Joyce (portrayed by X-Men actor Shawn Ashmore) to a TV within the first few minutes of the game. Though the plot starts with Jack rushing to meet his brother for the demonstration of a revolutionary new technology, time can still be taken to stand around in front of a set and watch a video. The player expects more of these as the game goes on, but, instead, Remedy largely forgoes the constraints of these short videos for something bigger: live-action, full-length episodes of its very own science-fiction drama series.

multi-colored ribbons of exploded fireworks hang suspended in mid-air

Quantum Break is not so much a tribute to pulp sci-fi—it’s an embodiment. After his brother’s time machine malfunctions, Jack finds himself imbued with superpowers. His exposure to time-manipulating “chronon particles” gives Jack the ability to freeze the world around him, speed from place to place, and create pockets in space where nothing moves. The accident that gives Jack his powers also sets the end of the world into motion—a calamity dubbed The End of Time in which everything in existence simply stops. In attempting to avert this catastrophe, Jack is opposed by former friend Paul Serene (Game of Thrones’ Aidan Gillen), the founder of Monarch Solutions, a mega corporation with a vested interest in the shape the oncoming apocalypse will take.

That a brief summary of Quantum Break’s plot is necessarily convoluted should provide some idea of how the game itself unfolds. Just as Max Payne and Alan Wake couched themselves in crime and paranormal thriller conventions, Remedy’s latest owes a profound debt to the twisting plotlines and fantastic technology of the time travel genre.

Though initially off-putting, the game’s eagerness to explain the pseudo-science behind its various super devices, and the straight face with which it approaches the dramatic potential of time loops, becomes endearing. As Jack, the player spends much of her time shooting through groups of enemy soldiers across a series of competent, but unexceptional gun battles. It’s only in the handful of moments when the world freezes—time “stutters,” Jack able to move while everyone and everything else remains motionless—that Quantum Break exploits the design potential of its sci-fi conceits. There’s the impressive tableau of a party where multi-colored ribbons of exploded fireworks hang suspended in mid-air, and a scene where Jack attempts to escape a collapsing tanker, its steel guts having turned a great concrete dry dock into a several story-tall labyrinth. Otherwise, the game’s sense of character comes when control is wrested away for Quantum Break’s serialized TV show—four 20-minute episodes that run between the game’s playable acts.

In these episodes, a script that often falls flat in the rest of the game comes to life through fast-paced, ultra-corny scenes. Free of the technobabble that bogs down the computer-generated cinematics and fills the far too lengthy and frequent text logs, Quantum Break’s television segments are given no mandate but entertainment. The cast seems game for all of it and their performances—especially The Wire’s Lance Reddick’s portrayal of the dispassionately evil Martin Hatch—introduce a level of distinctly human enjoyment to the story, one that’s lacking from the exactingly detailed motion captures used in the rest of the game.

only the richest and best-connected may be able to survive

While the interactive core of Quantum Break is a serviceable ode to pulp science-fiction, the episodes are a reminder of what makes the genre enjoyable beyond metaphysical thought exercises: the ridiculousness. Much of this is the by-product of the glint in the cast’s eyes as they gnaw on Quantum Break’s glossary of terms (the “Lifeboat Protocol;” the “Chronon Field Regulator”). The rest comes from the low-rent charm of the episodes’ visuals. Take, for instance, the outfits worn by Monarch Solutions’ goons become cosplay writ large in live action, the same, sleek yellow-and-white design worn by the enemies in-game turning cartoonish next to actors in ordinary wardrobe.

This isn’t to suggest that the game is without substance. Remedy understands that, no matter how ridiculous its premise, proper genre fiction can use its immediate appeal as a Trojan horse for broader commentary. Quantum Break is eager to point out the ways in which the link between wealth and technology (especially in a corporate context) will become increasingly evident in the future. It makes a thriller out of the idea that, should super-advanced technology bring about a calamity, only the richest and best-connected may be able to survive the disasters they’ve caused. It isn’t much, but the connection between this message and our ongoing inability to implement government policies that mitigate the destruction of our natural world adds welcome depth.

Yet, despite the success it finds in both evoking and making good use of its genre trappings, Quantum Break is too uneven to fully capitalize on its strengths. Its TV episodes energize the plot only to see it grind to a halt with slabs of expository emails and notes. Its use of time manipulation creates fantastic visual effects and environmental navigation challenges in some sequences, before relegating them to power-ups meant to add flair to drab gun battles in others. In its previous work, the television sets that dotted Remedy’s games were extensions of already well-established tones. Quantum Break, in enlarging their length and complexity, turns them into a crutch that’s forced to support a game that can’t consistently match their appeal.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.