The quiet importance of the Minecraft soundtrack

At the 2012 Minecraft Convention in Paris, Daniel Rosenfeld—better known by his handle “C418”—gave a talk about his background in music and the process of writing the score for the Minecraft documentary. He seemed a little nervous (maybe not used to interacting with crowds without music as an intermediary), and he often made self-deprecating jokes to help ease the tension:

“Marcus [Persson] has a panel—why are you here and not at Marcus’s panel?”

“It’s easy for idiots like me.”

“Eventually I managed to make sort of decent music.”

Sweet as these asides were, the crowd usually didn’t take the bait.

But the digs he takes at himself aren’t just for nothing. Throughout the talk, Daniel is keen on demonstrating that anyone could make music the way he does. He only began recording music after his brother introduced him to Ableton (then a fairly new digital audio workstation that, in his brother’s words, even idiots could use), and after that, it was years before he was making anything that he would call “good.” But while Rosenfeld is thoroughly committed to his own ordinariness, it’s clear that he has something special.

Case in point: During his talk in Paris, Rosenfeld walked the crowd through every block of what would become the title music for the documentary. He features each instrument track, describing how he made every decision—“That sounds good enough”—and slowly stacking up all of the elements until the whole song was playing. Bass notes sampled from a detuned guitar hustle the beat; a synth theme performs aerial twists and loops; orchestral strings ascend in dramatic swells; and perfectly pitched voices howl out sustained tones. When the song ends, the crowd takes a breath and enthusiastically applauds.

That’s Daniel Rosenfeld: friendly, modest, and kind of a wonder.

///

When Rosenfeld sat in front of the crowd in Paris to talk about scoring his first film, he was just 23 years old. By this time, Minecraft was already well on its way to being one of the best-selling videogames of all time, and because he was responsible for all of the game’s sound and music, Rosenfeld had earned millions of listeners the world over. As a result of his work with Mojang, he had gone from his day job at a manufacturer of dialysis machines to a self-employed composer with a volume of fan mail big enough that he started a blog to keep up. But to hear him talk about it, you’d think he was just as surprised about his success as anyone else.

I spoke to Rosenfeld recently over Skype, shortly after he had returned from this year’s MineCon in London, and when I asked whether he had any traditional musical background that helped him get to where he is, he answered emphatically: “Oh absolutely not! In fact, I play everything badly. Basically, I have something in my mind, and I just learn it until I can do it. I record it once, and then forget about it.” Instead, Rosenfeld claims that most of what he knows he learned from listening to experimental electronic music, counting the Ninja Tune and Warp labels among his favorite sources.

Whether or not Rosenfeld ever had piano lessons, he definitely has a handsome endowment of musical intuition, and he comes by it honestly. Both his mother and father were involved in music in some professional capacity before beginning careers in other industries: his father taking up his grandfather’s profession of goldsmithing, and his mother studying physics and eventually working for an investment company. According to Rosenfeld, music in his family is pretty much just history: “They don’t really talk about [their musical background] anymore—just reminisce about it as if it’s a thing of the past that could never happen again.”

It was Rosenfeld’s older brother Harry who began to revive an interest in music in the house, mostly by adding simple soundtracks to drawings that he made on his 386 PC. Daniel rarely took an interest in his brother’s experiments when he was younger, but when Daniel was around 14, his brother finally hooked him on Ableton. “I started making terrible music—intentionally terrible actually—and that was so fun to me that I didn’t stop making music,” he said. “And eventually it wasn’t terrible anymore, it was actually, like … serviceable.”

Videogames were another important part of growing up for Rosenfeld, but because he didn’t have much money as a teenager, he gravitated toward free indie games. Eventually, Rosenfeld became involved in the TIGsource community, where he struck up an online friendship with Marcus Persson that would eventually lead to Rosenfeld writing music for Minecraft. “He was interested in the music I was making, and I was interested in the project he was doing,” he said. “One thing led to another, and we just decided to start working together.”

But Rosenfeld’s body of work extends well beyond music for videogames. His Bandcamp page lists over a dozen albums of original music, with styles ranging from moody, detuned synth grooves to driving, almost orchestral soundtracks to break-beats and ambient experiments. The common thread between many of these albums is Rosenfeld’s keen ear for layering harmonies and the neat, contrapuntal flow of his melodies.

Despite all the variety represented in his work, Rosenfeld says that his basic musical philosophy boils down to creating something functional: “I like to think of it as a tool, in fact, because a lot of the music I make is repetitive by design.” According to Rosenfeld, the repetition is intended to induce a state of relaxation or concentration, something that might be useful to listeners trying to work or get to sleep.

Ideas like these have deep roots in ambient music, probably the most salient example of which is Brian Eno’s seminal 1978 album Music for Airports, which is often casually credited as the foundational album of the genre. The story of Music for Airports goes that while Eno was waiting for a plane, admiring the architecture of the Cologne Bonn Airport in Germany, he was annoyed that the selection of music playing in the airport speakers was so inappropriate for the surroundings. And it wasn’t just that the soundtrack didn’t fit the building—it was also oblivious to the experiences of the people moving through the airport. Eno wanted to create music that would be complementary to these experiences, that would relax travelers, enable reflection, and, importantly, stay out of the way of the day-to-day operations of the airport.

The irony here is that, save for a short time when the album was played in the halls of La Guardia in New York City, Music for Airports never had the opportunity to make good on those promises. Instead, it was printed and served up as an experimental work by an experimental artist—an album to be listened to like other albums, central to rather than complementary to a listener’s experience. (Eno, if you’re reading this, I still love you.)

On the other hand, games like Minecraft that place players in stylized environments and afford players a significant degree of freedom are poised to take full advantage of this opportunity, and a few great ones have. It’s impossible to talk about ambient music in videogames and not mention Ed Key and David Kanaga’s Proteus in the next breath. In Proteus, players simply wander through the hills and forests of a procedurally generated island, all while the game’s music modulates according to the objects and circumstances of players’ surroundings. But Proteus still falls for the Eno paradox somewhat: while players are free to create their own stories as they wander, ultimately, their experiences aren’t so much mediated by the music and environment as they are founded in it. A beautiful game, Proteus can create spaces for reflection, but it also treats its music as a central feature of an experience rather than a complement to one.

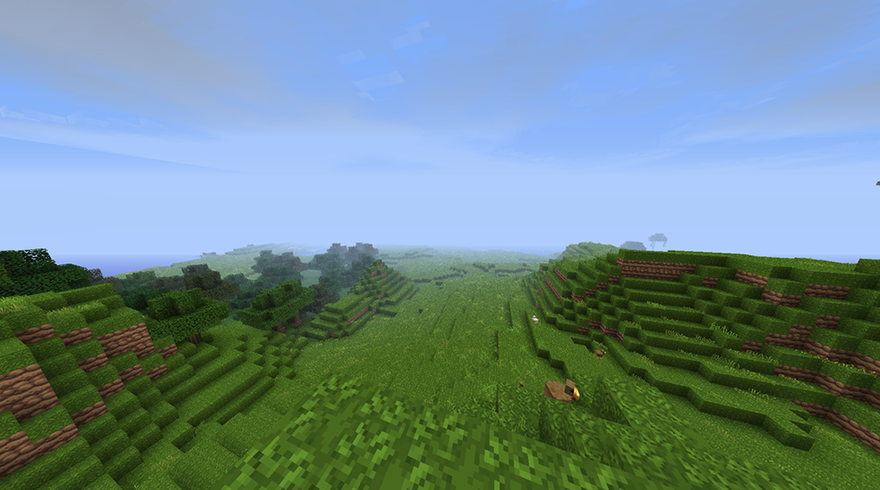

Minecraft is nothing if not a game that prioritizes players’ emergent stories first. While you can play it as a survival game, the real joy of Minecraft is in finding yourself in a unique world and trying to develop your own place in it. As a result, the music in the game takes a backseat and primarily works to enhance experience. Daniel Rosenfeld knows this, and like Brian Eno before him, he has a handle on the kinds of experience that he wants to enable: lonely ones.

“When I started working on the game,” he told me, “it was just a prototype of a world that is procedural—it didn’t go on infinitely, but it was a very lonely experience back then. We didn’t implement online multiplayer, so it was by design very lonely. And luckily, it still turns out to be kind of a lonely game, even if you play with your friends.”

Rosenfeld also likes that music is only triggered at random times in the game, rather than tied strictly to specific times, events, or objects. He believes that this allows players to assign significance to moments when their efforts are unexpectedly met by music: “Making the music random has the side effect of whenever the player is doing anything significant—that they personally think is significant—and the music kicks in, they remember that moment very vividly … It’s all up to the player. They decide subconsciously that, ‘Yeah, this moment is specifically made for me.’ Which is fascinating!”

By attempting to provide a platform rather than a focus for player experiences, Rosenfeld’s work for Minecraft participates in a decades old project of evoking ambiance through music. What makes the music special, however, is its sophisticated interpretation of the Minecraft world that is sensitive to the kinds of lives and stories we build within that world. The music holds up well to attentive listens, but it doesn’t have to be about that: just let it move over you the next time you’re fortifying your obsidian castle against creepers.

///

On August 21st, Ghostly International will be rereleasing C418’s Minecraft – Volume Alpha in physical format. You can preorder the album over at Ghostly International’s website.