The story of the man behind the Doonesbury Election Game

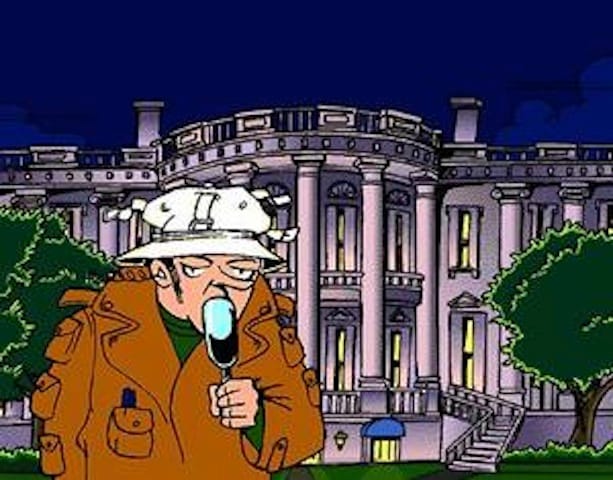

When Garry Trudeau decided to turn his legendary comic strip, Doonesbury, into a computer game, Randy Chase was the natural choice to build it. The man behind the seminal political simulation, Power Politics, Chase was familiar with both the world of politics and what it took to build a game based on the farcical and manipulative world of political campaigns.

Chase was politically simpatico with Trudeau, but their ideas about the ideal political game were different. While the Oregon-based Chase had developed a philosophy of political balance in his games, Trudeau wanted something much closer to arch-liberal spirit of his strip. The Doonesbury Election Game, which could have been Chase’s moment in the sun, came out in 1996 to little fanfare. Chase died in 2009 of a heart condition in relative obscurity. But he left behind some of the most sophisticated political simulators ever created. Here is his story.

///

In 1991, Chase created a prototype of Power Politics on a whim, as a way to teach himself the coding language Visual Basic. A developer friend brought the game with him to the ‘91 Consumer Electronics Show and came back with news: “Randy, I’ve got some orders for your game!” Chase replied, “What game?” But where Chase saw an experiment, others saw potential. So he went to work, preparing a game about the 1992 election for official release with Cineplay Interactive.

Chase had barely learned to code. “I can still remember him sitting on the stairs one night with his head in his hands,” says his wife, Lyn. “He said ‘I can’t do this. I can’t do this.’ He was already well into the project and he’d run into a problem. I just told him, yes you can. You can do it.”

Chase worked on his game for five months, often for eighteen hours a day. Meanwhile, Cineplay Interactive was on its last legs, and wouldn’t be able to properly support the game’s release. Chase’s first game, to which he’d dedicated five months of his life, made him a total of 3400 dollars. Lyn was crushed, but Chase was just getting started: “No, no you don’t understand, dear. I got my name on a box!”

///

Chase always had an obsession with politics. He viewed games as a way to challenge the player to think through things that they may not have otherwise. On the Power Politics website, Chase declared his intention to design games that would help the player “explore game concepts that make you think, not just about the game, but about the world around you.”

The mechanics of Chase’s political simulations allowed for the player to discover all sorts of nuances in America’s political system.

In an interview with George Magazine, Chase described the type of game he wanted to develop as “activism software.” (On his website he notes his publisher’s frustration with that term: “Traditional software publishers get real nervous if their developers start talking about activism and political issues; they’d much rather have us talking about the amazing graphics when the player blows something – or someone – up!”) What he had in mind was a game that would challenge a player to think outside of their own assumptions, to consider the world they live in. Ultimately, he hoped that the game experience might change players’ minds.

The mechanics of Chase’s political simulations allowed for the player to discover all sorts of nuances in America’s political system. The player acted as campaign manager, hiring staff, commissioning polls, setting up fundraisers and even playing dirty tricks on opponents, mistakes which may or may not come back to haunt the player later. The games were based on actual statistical data culled from the census and other sources. The candidates available were real candidates, with actual strengths and weaknesses.

Most important to Chase was that the game didn’t take sides. “Randy was absolutely committed to a fair and level playing field,” says Lyn Chase. “He said there was no point in wasting the time and money on a game if it was slanted at all. With his third version of Power Politics, he would get calls from people and they’d say ‘This is clearly designed by a liberal and it was very obvious.’ And then we’d get calls from people and they’d say ‘This is clearly designed by a conservative and it’s very obvious.’ He was so proud of that, because you really couldn’t tell. He was very, very skillful at keeping his politics out of that game.”

///

That personal design philosophy became a liability in his collaboration with Garry Trudeau. While Chase remained committed to creating a politically-balanced experience, Trudeau had expectations that were very much in line with his comic strip, both in aesthetic and tone.

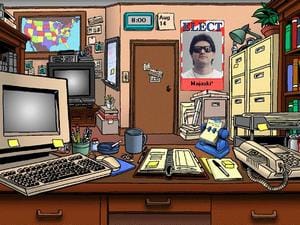

Trudeau had had the resources to put together an extensive team of developers, including a graphic artist committed to designing the user interface for the Doonesbury Election Game. One day Chase’s producer called with some news.

“You know that screen with the file drawers?”

“Yeah,” Chase said. “You don’t like that one?”

“No,” he said. “Gary likes that one. He just doesn’t like any of the others.”

Trudeau put his own artists to work to redesign the dozens of already-finished screens.. It may have been a better fit for the Doonesbury franchise, but all Chase could see was lost potential. “This game was a very sophisticated, multi-layered simulation of presidential politics,” said Lyn Chase. “But people thought it was just some cute little nothing – that it was just some liberal stupid little toy.”

Doonesbury wasn’t seen as “stupid,” but in 1995 videogames typically were, and Chase’s political simulations required a unique aesthetic to draw attention to the thoughtful and reasoned tone the game meant to convey through its mechanics. The game appealed to Doonesbury fans and those who took the time to explore the game itself. That limited appeal, plus the lack of marketing muscle from then-fledgling publisher Mindscape, caused the game to suffer commercially.

Trudeau had already pledged his royalties from the game to charity, and so, as Chase’s son, Eric, said, “He didn’t really have a stake in the game’s success.”

Still, Chase salvaged some things from the cutting floor. Explains lyn Chase, “In Power Politics 3 he went ahead and used the graphics that were thrown away from the Doonesbury game in favor of the Doonesbury style, and produced a beautiful game.”

///

In addition to the Power Politics sequels, Chase went on to develop Spirit Wars, an online-only card game that blended Magic: The Gathering with elements of Risk and chess. The game became famous for its friendly and generous player community, a fact that Lyn Chase sees as part ofher husband’s legacy. “We had people,” she says, “who met because of Spirit Wars. Some have gotten married; some have got divorced; some have had babies.”

Utlimately, what Chase’s games will be remembered for, in terms of both politics and play, are respect and civility. He encouraged his players to have perspective in the midst of campaigns and in the midst of the game. Win or lose, good game or bad, Chase’s games taught players that there are more than results at stake, and that behind every contest there is a human being. It’s a lesson, of course, that could be used in this acrimonious campaign cycle. Lyn Chase put it simply: “He loved his players, and they loved him.”