One way to think about videogames is to split them between “game” and “play.” Fighting games and competitive online multiplayer games (think BlazBlue: Calamity Trigger or League of Legends) exemplify “game,” with their focus on skill and accomplishment. Meanwhile, big, unstructured experiences such as those in Just Cause 2 and Terraria demonstrate “play,” by focusing on discovery and free-form player activity. But I can’t help but notice a somewhat narrow range of strategies on how games implement play into their experiences. There are other ways to encourage play than open worlds and loose mechanics. Boku no Natsuyasumi is proof enough of that. This obscure, late-life PlayStation game creates a more structured play than many games before or since.

Set in the 1970s, Boku no Natsuyasumi places you in the role of the eponymous Boku, sent to live with his uncle and his family for summer vacation. (The title translates to both My Summer Vacation and Boku’s Summer Vacation.) You can spend your time as you please during this vacation, engaging in a wide assortment of activities. You can fish, fly kites, catch bugs, water plants, and much more. However, at least compared to other games, these individual activities aren’t very good at encouraging play. Unlike Goat Simulator or Surgeon Simulator, fishing doesn’t feel goofy—just plain and utilitarian.

Yet Boku no Natsuyasumi was never “about” these activities. It was about its world, and how that encourages play. Unlike a lot of play-focused games, Boku doesn’t employ an open world. At the center lies Boku’s surrogate home. It’s a modern Japanese two-floor house, complete with tight rooms, abundant wooden surfaces, a tool shed jutting off the side, and a tiny ofuro nestled away in the back of the kitchen. This small house serves as the hub for Boku’s summer adventures, as all the areas he can explore branch away from it. Some examples include a pond surrounded by small caves and a waterfall; an open field with sunflowers as far as they eye can see; a shrine with three different size Buddha statues; a cliff overlooking a beach, and so on.

It’s definitely a strong contrast against the open-world design that seems so popular with play-centric games. Compared to them, Boku’s world feels very controlling. This is not a world that’s content to leave anything up to luck. It would rather craft a restrictive space that inevitably leads the player to moments of play. And it works, at least if my own experiences are anything to go by. I encountered a wide array of memorable events within my brief summer vacation. Some of them were relatively minor. I’d spend days poking a beehive or chopping down a tree in the hopes of opening up a new area. Other moments practically made an entire day (or, in my case, a night).

The nostalgia both puts you in a mood that’s conducive to play and lends the world credibility.

It’s important to understand that Boku no Natsuyasumi structures time just as strongly as it does space. Barring narrative quirks, each day follows the same template: Boku wakes up with his family at the rooster’s crow, ready for family exercises. They sit down to eat breakfast, and then everybody wanders off to attend to their own business. This time is where most of the game’s activity occurs. Boku wanders the areas around his house until evening, when his uncle brings him (and presumably the rest of the family) back together for dinner. The family spends the rest of the night socializing before going to bed.

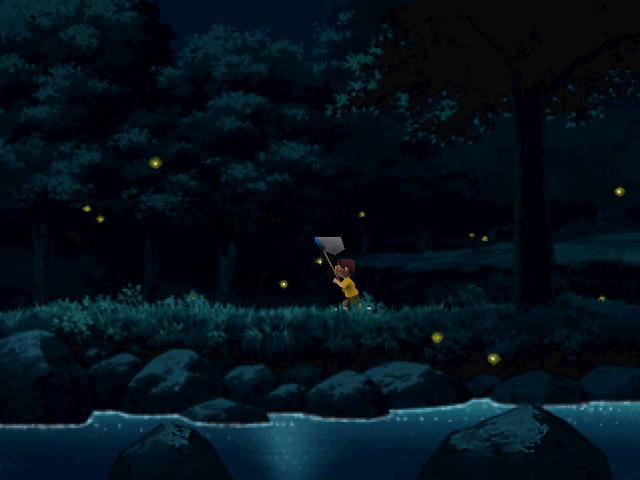

After repeating this cycle for maybe a week’s worth of summer vacation, I realized that, technically, the game wasn’t restricting Boku to the house at night. Boku’s foster parents weren’t concerned with keeping him inside. They had their own business to attend to. This newfound knowledge guided me and Boku outside the house to see what the night had to offer. Fortunately, I chose a night when fireflies dotted the areas just outside Boku’s house. Butterfly net in hand, I proceeded to spend my time catching the bugs until Boku’s uncle brought him back to the house after letting Boku have his fun.

Although it might seem like my actions violated the game’s structure, the truth is that the game’s structure is what led me to this moment in the first place. Although I went against the usual family routine, it was only because there were no other times of day when fireflies would come out. I had to play within the game’s time structure to find this opportunity at all. Similarly, the world structure also led me to play. I still had the freedom to do as I please, but with the world as tight as it was, it was almost a foregone conclusion that I’d stumble across an event like this if I explored even a little.

And so we begin to understand how Boku no Natsuyasumi structures play in comparison to so many other kinds of games. It situates the freedom we typically associate with play in a framework that almost forces the player to utilize that freedom. Of course, that’s a difficult balance for any game to achieve. We typically associate tight spaces in games with overtly leading experiences. Boku finds a nice balance, though. The restrictions feel so natural to the world that you hardly notice them. You’re more likely to think that you did something because you wanted to, not because the game wanted you to.

Of course, how Boku no Natsuyasumi constructs its aesthetic is just as important as how it constructs its space. Boku’s world is largely based in nature, dirt paths leading Boku through dark forests and by quiet riversides. The game paints all this with warm summer colors—greens, yellows, oranges, blues. The nostalgic feeling these images evoke are a perfect complement to the restricted world design. They both recall a time not only when play was a part of your everyday experience, but also to a time with strong external structures like school and parental supervision. The nostalgia both puts you in a mood that’s conducive to play and lends the world credibility.

This is certainly a departure from how most play-centric games induce play. Most of the time, they appeal to play with open worlds and absurdist humor. However, it’s just as important to consider possible alternatives, like those that Boku no Natsuyasumi offers. This game thoroughly explores the many levels games can use to structure play: space, time, emotion, and everything in between. Its meditative tone provides a stark contrast to the bombastic open worlds we associate with free play today.