Remembering the beautifully boring MMO Star Wars Galaxies

There aren’t many games where the player can be a club dancer, strapped-for-cash and performing for tips in a sleazy bar. There are fewer where that bar is filled with fish people and space bears.

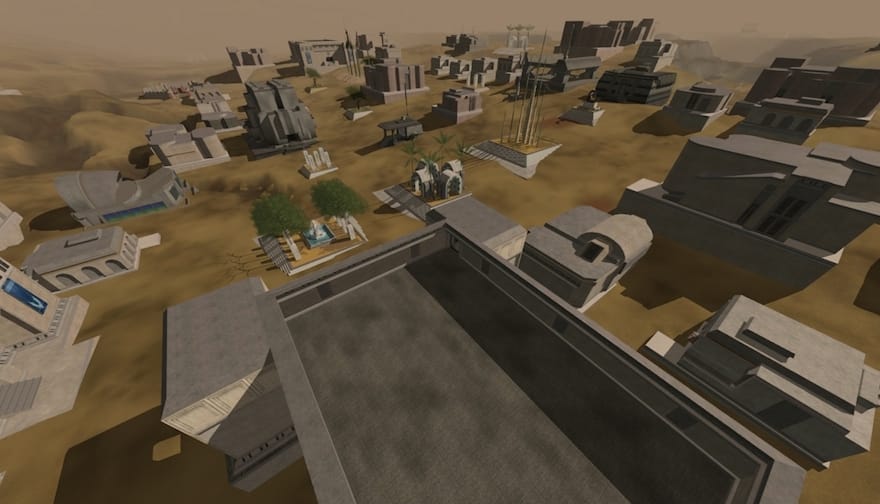

When Star Wars Galaxies first released in 2003, it did so under the tagline “Live in the Star Wars Universe.” A simple slogan that could initially be read in a number of ways, but one that turned out to be diametrically opposed to the rest of the Star Wars game library over the title’s lifetime. As opposed to the epic quests of games like Shadows of the Empire or the previous year’s Jedi Knight II, which could perhaps be summed up with “Save the Star Wars Universe,” Galaxies billed itself as a more personal take on the familiar space fantasy world. Players could still play out those movie-inspired dreams of being smugglers or bounty hunters, yes, but these more glamorous callings were only able to succeed because of the player-driven socioeconomic systems propped up by a whole in-game society stretching far beyond the fantasies of kids playing Han Solo and Boba Fett in their backyards. As the motto implied, this was a large-scale world inhabited by players who, if they so desired, could simply live meaningful lives on the small scale. In a way, Star Wars: Galaxies was the Uncle Owen and Aunt Beru simulator we never knew we wanted.

Rather than relying on a simple variation of the basic warrior/thief/mage class structure so common to other games of the same type, Galaxies instead debuted with a multi-tiered profession tree of over 40 different jobs, each of which could be mixed and matched to a player’s content so long as they had enough skill points to invest across them. Among these jobs were combat professions like commando or Teras Kasi Artist, but also titles like politician, chef, musician, tailor and image designer. Players who didn’t like the idea of adventuring through the mud could instead focus on running cities, cooking healing items, helping other players with status-improving songs, crafting clothing, or changing the look of other players’ characters … all for a fee, of course. Those who were good enough at it could even open up stores of their own and become famous as brand names. It wasn’t uncommon for combat-oriented players to have a trusted armor guy or spaceship parts guy, regularly making pilgrimages to their shops, which were all set up in player-built housing within player-built cities, which were themselves run by a mayor who could take taxes as needed. You could essentially open a mall in the Star Wars universe, which proved to be more compelling than you might think.

This was because Galaxies didn’t rely on non-player characters to fulfill the more mundane roles of its world. Many massively multiplayer games have crafting systems, of course, but Galaxies’ was more expansive than most. Whereas crafting in World of Warcraft is essentially a side-activity meant to provide players with a few small bonuses that quickly become outpaced by higher-level loot earned from fighting bosses, Galaxies’ crafting system was the best way to earn many essential items, from weaponry to vehicles. If someone wanted the best armor in the game, then they went to a player armorsmith, not a dungeon. If someone wanted to re-customize the look of their character, then they went to a player image designer, not a computer-controlled stylist. If someone wanted to buy a droid (Galaxies’ answer to the pets of other games), then they went to a player engineer, not a non-player breeder. This lack of competition from non-player characters forced players to rely on each other for goods and services, creating a robust player-driven economy that gave crafting or service-based characters as much purpose within the game’s world as those toting guns. And nothing symbolized this economy more than the Cantina.

This was due to “battle fatigue,” a clever little tactic used by the designers to turn their watering holes into actual gathering places. As combat-oriented players spent more and more time on the field, they accrued various stages of a status effect that would reduce the efficiency of their attacks and make them more vulnerable to damage. Initially negligible, this battle fatigue would absolutely doom players who went too long without getting it treated, and the only way to do so was to relax at a Cantina. Watching any of the entertainer professions perform for a long enough time would not only cure the nasty ailment, but also replace it with various positive bonuses. This meant that Cantinas quickly became host to dozens of adventurers all watching the various performers on display, which in turn drew entrepreneurs. Scenes of characters from every class and race shouting reminders to tip your entertainers, hocking their wares, and advertising personal stores became common in Cantinas. The result looked right out of the films, but more than that, it had managed to create an actual incentive for players of all stripes to consistently get together in a single spot. This was an MMO with a bar scene.

This was an MMO with a bar scene

When I first picked up Star Wars Galaxies, I was still in middle school. I hadn’t yet grasped the shear appeal of playing as a Wookie hairdresser on Naboo who also serves as mayor over a small hamlet of various artisans just outside of Theed. I just wanted to blow shit up! My time was largely spent in various hunting parties as I worked up my marksmanship skills until I could become a bounty hunter. Along this path, I spent many hours recuperating from questing in Cantinas, and not only came to appreciate just how friendly the community was, having been brought together and encouraged to cooperate and swap stories by our shared battle fatigue, but also how diligent the entertainers were. I felt as if I had owed something to them because I took part in their services so frequently. I tipped generously, and when I finally did become a bounty hunter and needed a good way to earn cash for all my shiny new blasters and thermal detonators, I started up an alternate character as an entertainer.

I whipped up a Twi’lek dancer, started her off on Tatooine (I wanted to hear that sweet jizz music while I danced), and set to work paying off my bounty hunter’s equivalent to student loans. Unfortunately, as a newbie to the dancing gig, I quickly realized that I wasn’t attracting any customers. Being so low level, my dancing wasn’t able to heal battle fatigue or pass on bonus effects as effectively as the more seasoned entertainers, and I could only entertain one person at a time. Not to be dissuaded, I simply moved my act to the privacy of the Cantina’s kitchen area and started practicing until I was ready for the big time. At first, I was willing to grind this out manually, but after a while, I came to understand that doing so would have taken hours more than I had as a busy student. So I set up some macros, and for the first time ever, I left my computer on overnight to power-level a character. It wasn’t blowing up bad guys that gave me my first experience as a “power-gamer,” but dancing in a club.

The result of my “training” was a respected addition to the Mos Eisley Cantina scene. Because practically everyone in the Galaxies community required the service entertainers provided, we found ourselves rather appreciated by the other players. Tips weren’t mandatory, but few people rarely stole free entertainment. I quickly attracted a clientele and the creds started flowing in at a fairly steady rate. I even had a few regulars. Once, a guy actually asked me out on a date. When I told him my age, he politely apologized and left me to my business.

And that’s what it was: a successful business. Outside was a universe full of Rancors and AT-ST Walkers, but rather than adventuring, I decided to engage in local business. This may sound like the most boring way to experience Star Wars, but it actually made me feel something few other MMOs have: it made the world feel alive.

Raph Koster, the former creative director for Star Wars Galaxies, summed this up well when talking about the game’s early days for an article over on Gamasutra:

“But the game was shaping up…Players had formed governments…Entertainers were going on tour…People were building supply chain empires and businesses with hundreds of employees.”

an interconnected society of not only heroes, but also shopkeepers, hairstylists, and local bands

True, I didn’t abandon my bounty hunter. I wasn’t about to pass up a game that let me hunt down other players. But doing so did require primo equipment. Thankfully, I had my little side-operation to keep me funded. Being a bounty hunter made me feel like I was exploring the Star Wars universe, but being an entertainer made that universe feel worth exploring. If the recent Star Wars: Battlefront is a diorama of Star Wars, then Galaxies felt like a living, breathing world. It was full of players with their own individual playstyles and goals, each relying on people from different strata of society to help them succeed. This is where the tagline “Live in the Star Wars universe” took its shape. As a player in Galaxies, you weren’t necessarily trying to save the world. That was Luke Skywalker’s job. You were just an average person living one of any number of possible lives. You were part of an interconnected society of not only heroes, but also shopkeepers, hairstylists, and local bands.

This community was the real strength of the game. When Elder Scrolls Online launched last year, it did so with a storyline claiming every single player was the chosen one destined to save the world. Rather than have players work together, this framed them as competing for space to be the one great hero of destiny. By avoiding this, Galaxies allowed itself to do something rarely seen for an online space. It cultivated a friendly society where players relied on and appreciated each other rather than mocking each other. After all, you can laugh at the shipwright for choosing a crafting class all you want, but when you need a new engine part, who will you turn to?

This, unfortunately, didn’t last forever. In late 2005, in an attempt to compete with World of Warcraft, Star Wars Galaxies’ multifaceted profession system was dropped for something resembling WoW’s more standard classes. Players were encouraged to take on “heroic roles” modeled after their “favorite characters from the movies.” Jobs were consolidated, and with that, many of the characters players had created in their heads weren’t able to exist in this new world. Unfortunately, this backfired in what many within the community were calling a mass exodus to other, competing titles. Sony Online Entertainment stopped releasing official subscriber reports for the game, although hacked information placed the amount of players logged into a game on a typical Friday evening as being around only 10,363 by 2006. Players simply didn’t want to play as Not-Han Solo. Not every player wanted to be a hero. There were plenty of other games for that. They wanted to live in the Star Wars universe, not save it. And if their preferred life was dancing in a bar somewhere, they felt little reason to stay.

Hopeful, I stayed on after the release of what has been referred to as the NGE (short for “New Game Enhancements”) for a small while just to see where the game was headed. What I got in return was a once-beloved Cantina that had been rendered a ghost town and a list of bounty hunting jobs with no more players to challenge.

Feeling defeated, I eventually moved to World of Warcraft alongside the rest of my friends. It was a drastic shift, but with help from veteran players, I found myself warming up to Azeroth. It was filled with many of the same design decisions that bothered me in the NGE, true, but because it had been built around them as opposed to having them hastily stapled on top of a pre-existing system, they didn’t irritate me as much here. Rather than the confused patchwork that Galaxies had become, Warcraft functioned like a well-oiled machine, and kept me invested in MMOs until I chose to quit during high school to focus on my social life.

I watched quietly when Star Wars: Galaxies officially accepted its fate

I stayed away from MMOs for a long time after that, afraid of the drain that they could have on my free time. I watched quietly when Star Wars: Galaxies officially accepted its fate and shut down in 2011. But when The Old Republic was announced, my interest was piqued. “Maybe this one could do it right,” I hoped. “Maybe it can make up for what happened to Galaxies.” I knew it was unlikely, but it was enough to get me to follow the game. I didn’t dive in for a paid subscription at launch, but when Old Republic finally went free-to-play in 2012, I knew I had to at least give it a try.

For my first character, I decided to play a Sith Inquisitor. One of my biggest regrets from Galaxies was that I never really spent much time playing as an Imperial. Again, I was an idealistic kid, and my sympathies were with the Rebels. But as I’ve gotten older, I’ve grown more attached to the particular aesthetic surrounding the Empire, if not their ethics. I was hoping playing as a Sith would help touch on what I had missed when I was younger.

Instead, what I found was the same structure I remembered from World of Warcraft, but dressed up in Star Wars packaging. The zoned off leveling areas, the “Bring me 3 space rocks” quests, the “kill 10 space boars” tasks—it was all familiar. Once I unlocked the Sith Assassin class, it became clear to me that I was simply playing a Rogue by another name. I tried again with the Imperial Agent class, hoping I would find a more inventive experience with a non force-user, but neither of these glamorous roles satisfied me as much as my dancer from Galaxies.

Rather than the multifaceted profession tree of Galaxies, where I felt I was able to create a character that I felt was cool, Old Republic’s classes had me feeling like I was simply picking from a small number of pre-made characters someone else thought was cool. The Galaxy felt small again, and I had little reason to stay.

The Old Republic is a fine game, but as an exploration of Star Wars, its connections to the series felt superficial. One of the most famous scenes in A New Hope is the early one in the Mos Eisley Cantina. Here, moviegoers saw bizarre alien races of all types simply having a drink in skeezy dive bar. The world felt like it had grit to it, and the room seemed full of possible stories. In comparison, my experience with The Old Republic felt pristine. There were no gathering places, and everyone was too busy playing Darth Vader to stop and acknowledge the smaller world around them. In a community full of hundreds of Sith, that weird werewolf sitting at the bar doesn’t get a name. We don’t learn that the guy with the V-shaped head blew all his money on salt and juice. We’re never told that the guy that looks like Satan is a war criminal with a particular taste for jizz. There’s simply no time for them, when every player is out to either save or conquer the galaxy. When these minor characters are cut out, the world ironically feels much smaller. The Galaxy doesn’t feel lived in, and with nobody for Luke to save, his quest feels pointless. This is something Galaxies understood.

In Galaxies, the people who would have been background characters in other games got to tell their stories. This gave us a new look at Star Wars from a street-level perspective, something the films had always hinted at with its underworld, but had never given the spotlight, choosing instead to devote the main story to Emperors and Princesses. By exploring the everyman of this sprawling world, Galaxies honored its source material while at the same time discovering a novel approach to exploring it. It gave its players the chance to be anyone they wanted, no matter how boring, and that proved to be far more attractive to its community than dressing up as Luke Skywalker and holding a plastic lightsaber.