Review: Cards Against Humanity

When I received an email from Ben confirming games night was on, I decided to invite a coworker of mine, Anna, who had recently moved to the city with her husband Rich. Just like Ben, Anna and Rich are both British and nice, so I figured it would be a perfect fit.

Over the next 24 hours I started to reconsider my matchmaking abilities. What if Anna and Rich and his friends were of a different social class than Ben? From what I gather, the Brits are pretty picky about that kind of thing, and for all I knew I was torpedoing the favorite part of my week. What if they weren’t as nice as they seemed the one time we hung out outside of work? What I needed was a plan—something to make sure that we all got off on the right foot so that I wasn’t blacklisted from future games nights because of my uncultured and socially oblivious coworker and her jerk of a husband. What I needed was Apples to Apples.

As far as icebreakers go, Apples to Apples never fails: it is dead-simple to play, and is much more of a social lubricant than a hyper-competitive round of one of the countless Carcassonne expansions. Released in 1999 by Wisconsin’s Out of the Box Publishing and bought by Mattel in 2007, Apples to Apples has in recent years joined the “mainstream” boardgames (Monopoly, Scrabble, Jenga) in the aisles at Target, CVS, and other chain retailers.

The reason for its success comes down to a novel yet simple gameplay mechanic that encourages knowing your audience. Players draw cards printed with nouns like “Rogaine,” “Inflation,” and “Cockpit Recordings.” One player, chosen as the first Judge, randomly draws from a deck of adjectives like “Explosive” or “Patriotic.” The remaining players each submit a noun from their hand, the Judge selects the best noun for the adjective, and the winner receives the adjective card as a prize. A new player becomes the Judge, and this continues until one player wins by collecting the requisite number of adjectives.

In A2A it is sometimes possible to force a combination of cards that pushes the boundary of good taste. But making these matches—e.g., choosing “Anne Frank” as the response to “Sultry”—usually feels like tuning into Howard Stern when you go to the airport to pick up the visiting cousins from Ohio that you haven’t seen in six years. Sure, you might get a nervous chuckle out of Uncle Zoom, but Aunt Darla and the twins are more likely to feel uncomfortable than applaud you for your great taste in radio.

Instead, a good game of A2A accomplishes what an icebreaker in the first week of college is supposed to—it manages to be fun while helping its players learn more about the people they are playing with. As I played my way through my first game of A2A, I started to spot the card-pairing preferences of my fellow players, and so was able to adapt my strategy to account for Josh’s affinity for absurd pairings, or Ben’s taste for “subtle” combinations.

“What did Vin Diesel eat for dinner?”

When Ben told me that there was something better to play than Apples to Apples, I didn’t want something better. I wanted something safe: the game version of sipping tea, pinkies extended, making small talk about the cricket.

The proposed alternative was Cards Against Humanity: a game that is in many ways a clone of A2A, if the clone’s parents decided to raise their child on a strict diet of Southern Comfort and marijuana cigarettes. In fact, A2A and CAH use the same exact mechanic, but their respective content produces extremely different games.

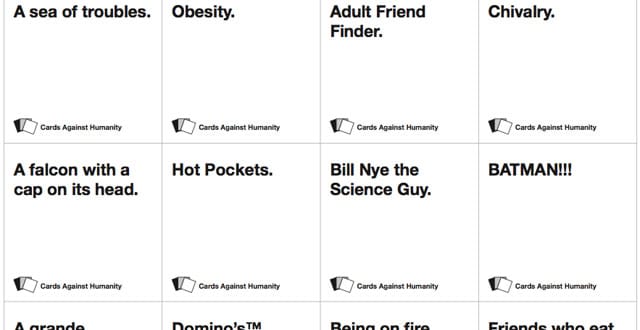

In Cards Against Humanity, players are dealt a hand of white Answer cards, generally nouns like “Harry Potter erotica”; “Sarah Palin”; “That one gay Teletubby”; “All-you-can-eat-shrimp for $4.99.” One player, called the “Card Czar,” draws from a deck of black Question cards—e.g., “Life was difficult for cavemen before __________.” Again the goal is to win a set number of rounds by producing the card that the Card Czar deems his “favorite.”

In CAH it is not nearly as important to pay attention to the individual personalities of fellow players. Since questions like “What did Vin Diesel eat for dinner?” don’t really beg subtle answers, the cards provide little opportunity to demonstrate a subtle understanding of people. What matters most, then, is a player’s ability to read the tone of the room as a whole: what level of sexual perversion or nonsensical racism will initially be tolerated; and as the game progresses, which pairings will shock or otherwise provoke a response from people who have spent the last 30 minutes making jokes about “Testicular torsion” and “Rip Torn drop-kicking anti-Semitic lesbians.”

My carefully engineered attempt to ease Anna and Rich into the group went down in flames. There was a stunned silence following the inspired, undeniably vulgar combination that gave Rich the first points of the game. It is too offensive to print, but is comparable to:

What would Grandma find disturbing, yet oddly charming? Pixilated bukkake.

Anna shot him an appalled look that managed to communicate both “This is the man I married?” and “We are definitely having a conversation about this when we get home.”

A moment later, the room broke into uncontrollable laughter. Rich was safe, and we became firmly entrenched in a game that lasted for more than two hours. And though I didn’t learn anything personal about the 20 or so people who cycled in and out of the game throughout the evening, it didn’t matter. What happened instead was just as fun: a night of non-sequitur, offensive humor in the vein of my generation’s cultural touchstones like Mr. Show, with CAH recruiting its players as both writers and actors. And though Ben has yet to invite me back for another games night, I like to think that has more to do with Anna and Rich’s social failings than mine.