Revisiting the enduring horror of Far Cry 2

The Far Cry series has always dealt in discordance. Those hyper-saturated blues of travel agent brochures and the high-contrast greens of the indigenous flora, deliciously juxtaposed with the hyper-violence you were enacting on screen. It’s the calling card of the series, that contrast; travel fantasies gone wrong. But Far Cry: Primal, out in a few weeks, eschews that trait of the series in favor of a more muted palette. Its world is one untouched by pop culture aesthetics, it gets back to the dirt we supposedly rose out of in the hope that a retreat into our prehistory will rejuvenate the series. It seems appropriate, then, to revisit 2008’s Far Cry 2, a game whose anti-exoticism is at odds with the rest of the series, whose dirty, muddied visuals have more in common with Primal. Let us return to those brown vistas.

///

“I’m nearing my fucking limit, arsehole,” muttered one of the guys in Pala, the region’s capital, then undergoing cease-fire. The strain in his voice was frightening. He was ready to blow. Probably quite literally. Probably with a bullet in his or my head. I gave him a wide berth, careful not to face my gun towards him. I walked to the headquarters of the Alliance for Popular Resistance, handed my weapons in, and trudged upstairs to pick up an assignment to destroy the production site of a malaria antidote. A few days later I would be working for the other power group in the region, the United Front for Liberation and Labour, detonating explosives that would wipe out the morphine supply of the country. Everyone is desperate in this world, clinging on to whatever they can, trying to keep it together. Morality is totally absent; self-preservation is key.

Let us return to those brown vistas

At first it seems like moral ambiguity. Forget the binary decision-making of most videogames—the good and evil alignments of 2004’s Fable, or the renegade and paragon virtues of 2007’s Mass Effect—the outcome of your actions in Far Cry 2 are, in the first few hours at least, hard to read, obscured by the motivations of the two factions engaged in the civil-war. Who’s fighting the just war? Who’s on the side of the people? You juggle these questions throughout while constantly hoping your own role is that of the heroic outlaw, like Robin Hood. It’s hard to shake that hero narrative, but shake it you must. This isn’t moral ambiguity; this is moral certainty. As the player, you’re going to be complicit in maintaining instability: you’ll murder hundreds of people horrifically; you’ll destroy the abandoned homes of the population that has fled; and you will betray your “buddies”. Most importantly, you have no choice in the matter, in perpetrating and witnessing the horror that unfolds. Choice comes later, but only in how you interpret what unfolded on the screen.

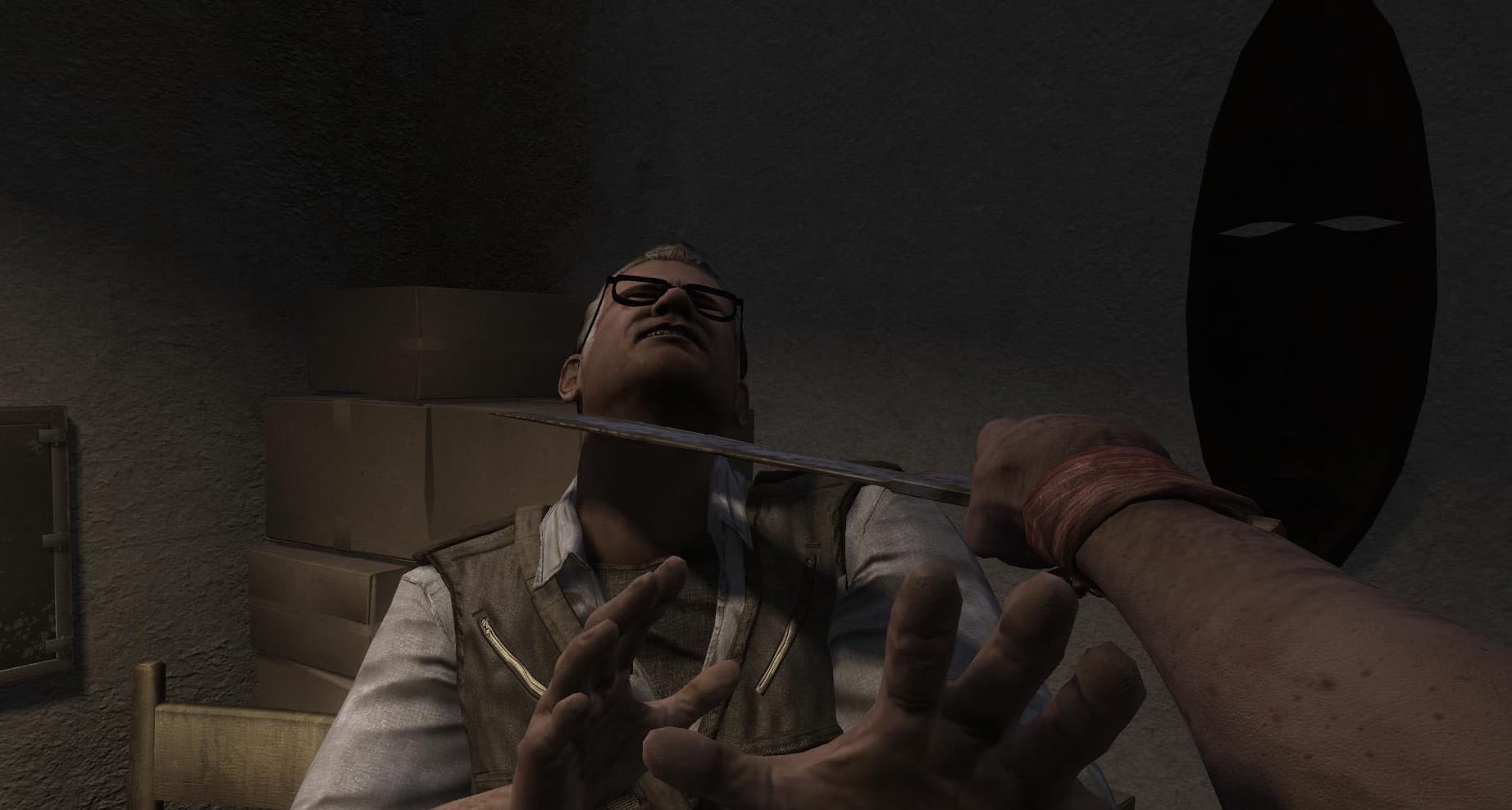

Far Cry 2 is unrelentingly grim in story. Such grimness is matched by the actions of the player as you find yourself using pliers to wrench bullets from your legs and hands, or a knife to lever out shrapnel. You’ll wince when you see these actions for the first time; the clicking back into place of broken fingers. What this does is put the onus back on the player. It’s through your body, your avatar, that you see the grim reality of the violence of which you’re a part. The stealth kills, for example, are profoundly undramatic affairs (in the context of videogames, it should be stressed). There’s no histrionics to the deaths, no protruding machete through the stomach, no slitted throat. You swipe, and the character falls. End of. The incentive to see these deaths is removed.

The killing of wounded enemies, by contrast, is presented more starkly. As an enemy mercenary was scrabbling around in the dust trying to reach for his handgun, I chose to unsheath my machete. I stabbed him in the stomach with both hands planted firmly on the handle, putting the weight of my whole body into the action. He screamed and his body convulsed. I held total power over this person, I chose to execute him like this, and the game presented this absolutely. There was nowhere else to look.

Those instances of execution, though, are rare in making you feel powerful. For most of the game it’s you, not the enemy, who is scrabbling around in the dirt, tracking back, hiding for cover, always within sight of death’s door. It’s the weapons, ironically, that are key in depowering you. They’re prone to jamming without notice, and this always occurs in combat under heavy use. Your momentary impotence compounds the tension, it feels like the game is actively conspiring against you. Work for these kills it says; improvise, employ other means, run if you have to. But it also stifles any attachment you might develop towards the guns. The gun is no longer welded to your arm as an extension and expression of yourself. It’s something you actively gather in-game, not something you endlessly customize in a weapon-porn external menu.

Far Cry 2 flips the fantasy of most modern war games into a nightmarish reality

There’s a sense that you’re something aside from a super soldier, prone to human error, even as you maintain your destabilising, heartless bastard schtick. The map helps reinforce this feeling as you navigate your way across Leboa-Sako (the northern region) and Bowa-Seko (the southern region). When you pull it out, the game doesn’t pause, you press the controller and the map appears; you’re navigating and route making in real time. It’s one eye on the map, and one eye on the road, or river, or scrubland that you’re travelling through at any given time. And splitting your concentration like this is hard, particularly when the map takes up such a large portion of the screen. Certainly it leads to a more sustained concentration on the game world itself, but there are times when it tips into frustration, when the effort required to play along becomes something like hard work. Unfortunately timed gun-jams also provoke this feeling, that sense of frustration, but they’re nothing compared to the outright hostility directed at the player through the respawning enemies that occur across the map

This is the big one with Far Cry 2, the potential game ruiner. Regardless of who you’re working for in the game at a given time, all soldiers in the region are hostile towards you, opening fire if you stray within their eye line. They’re situated on almost every road bend, every crossroads, and every hideout. And no matter how many times I gutted the same roadside blockade or make-shift camp these figures, harbingers of death and ruiners of fun, would reappear. They antagonised me, goaded me, and it made the environment almost insufferably hostile, a wretched place to spend any time. It should be chalked up as bad design, an oversight, but it contributes to the unending bleakness of the landscape these figures exist to service. It flips the fantasy of most modern war games (hello, Call of Duty) into a nightmarish reality. This is an unchanging map no matter what your decisions are, and your actions provide no tangible changes. You’re trapped, totally and completely. Halfway through the game you escape to Leboa-Sako, the northern region, and all you’re doing is swapping one perpetual horror for another.

This is important. The game world is an imagined horror, designed to emphasize the violent aspects of videogames. It very deliberately refrains from giving us a concrete setting; a named region or country. Sure, there are signifiers like the topography, the flora and fauna, and the placenames, all of which place it in a general central African-region, but you’ll never pin it down more than that, nor should you try. What this setting does is provide a framework for your actions. Chaos, instability, and hopelessness are the key features of this landscape, and it’s this context that provides the justification for your exploitative, violent actions. But the civil-war backdrop, and the impossibility of resolving it, ensures the violence plays out ad infinitum. It’s in that process, that perpetuity, that the violence becomes unfun, and it has to get to this point in order for the player to question it.

Far Cry 2, then, is less about the immediate politics, history and conflict of its unspecified setting than it is about the act of killing on screen. Despite this focus, it still manages to speak powerfully about the perpetual nature of violence in the real world. Like the best horror movies it ends on a note totally devoid of hope, of enduring horror. The smudged out browns and the pressing heat all contribute to that sense of terror, heavy and oppressive. Far Cry 3 and 4, though, speak of isolated incidents, one-offs determined by megalomaniac antagonists, their personalities reflected in the almost garish, tropical hues. They are, to some extent, more disposable. But in taking the series back to our prehistory Far Cry: Primal forgoes both that aesthetic and, potentially, the message. Perhaps it will share the observations of Far Cry 2, of the tireless human thirst for conflict. Perhaps not. But if the brown vistas of Primal fill me with even half the dread of Far Cry 2’s, it’ll be worth the trip.