Rocksmith 2014 entertains and educates, but is it edutainment?

You’ve no doubt heard the old adage that music is math. Rocksmith 2014 has me fairly well convinced that music is also a videogame.

For a game so gung-ho about its ability to teach, Rocksmith remains gun-shy about explicitly calling itself an education game. It doesn’t want to give the impression of Mavis Beacon holding a stratocaster; it wants to be the grizzled bluesman who got lucky enough to play rhythm for Van Morrison one night in 1980-something and gives lessons at Guitar Center now.

In spite of what Ubisoft might want it to be, the game is undeniably edutainment.

After having spent a good amount of time with Rocksmith, I can safely at that, in spite of what Ubisoft might want it to be, the game is undeniably edutainment. But don’t get the wrong idea. The word “edutainment” connotes some necessary evil no one really wants to learn wrapped in a half-baked game. Rocksmith is definitely not that. I think the best comparison is not to Math Blaster or even Rocksmith’s forebear Guitar Hero, but to one of the fallen heroes of the Dreamcast, The Typing of the Dead, a videogame about learning typing.

Obviously typing and playing guitar are hugely different tasks, but the ways in which they’re usually taught overlap. They’re both mechanical skills that require repetition and frustrated chants of “practice makes perfect” before they reward their students with some measure of skill. With a bad teacher, learning things like that can be unbearable. Thanks to edutainment, though, Trunchbull-esque typing teachers barking out which keys to hit have largely been replaced by games. Most of these games involve shooting asteroids, targets, or, in the case of Typing of the Dead, zombies. Typing of the Dead was great at teaching typing because it took an established videogame genre—the on-rails arcade shooter—and replaced its bullets with keystrokes, its heavies with sentences, its bosses with paragraphs. The gameplay metaphor worked because the life-or-death nature of play demanded high performance from the student, yet made failure—and, crucially, improvement—fun.

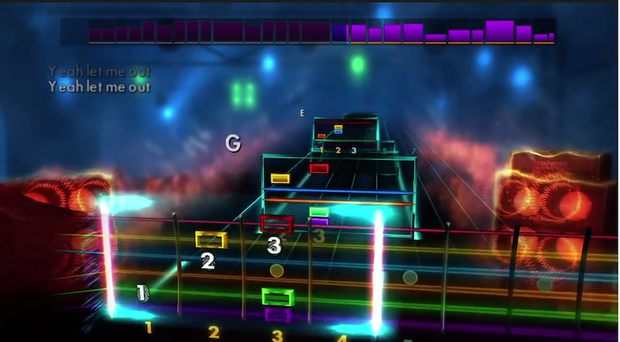

By contrast, Rocksmith’s main gameplay mode, Learn a Song, while incredibly powerful, dynamic, and accommodating for the persistent student, can still feel like drill-and-kill if you’re not careful. That isn’t an inherently bad thing—it’s how people have learned music for basically all of recorded history, give or take twenty years. But when you’re just not getting that one section of a solo, when the song slows down to a grueling 40% of its full tempo, when the Kinks start sounding more like a DJ Screw record than, you know, the Kinks, when you keep missing notes or bends or, worst of all, when you occasionally hit notes but don’t get credit for them, let’s just say you might feel like smashing your guitar. And not in the cool London Calling way.

Learning an art like playing guitar can be deeply frustrating, especially when you first recognize how deep and wide the valley is between you and Hendrix. Anyone going into Rocksmith with a guitar and a shred of optimism knows this. In order to play the game and get something out of it, you must be okay with being a little disappointed in yourself now and then. You can’t play all of the notes to begin with. In fact, sometimes you’re playing so few notes that you don’t even know if they really belong in the song. But when you’ve finally worked your way up to playing the whole riff at full speed, and the passages that you couldn’t make heads or tails of before start flying past (or, in Master mode, vanishing completely), it’s profoundly satisfying. Like, beating Super Hexagon satisfying.

I came to Rocksmith having played the guitar much the same way for the ten-or-so years I’ve had one lying around: slow folky stuff, lots of chords, very few leads, simple patterns. No music theory, no idea what an Aeolian or Phrygian scale is. Hell, most of the time I didn’t learn the bridge of whatever I was trying to teach myself. (Seriously, who remembers the bridge?) But coming to the game with a narrow range of knowledge about how to play guitar made learning new songs, styles, and techniques powerful, an expansion of what I thought I could do on a guitar.

If you have a guitar that doesn’t get enough love, Rocksmith might be the perfect way to rekindle an old flame.

Part of the reason that I played that the guitar for the same way for years was that I knew building skill would require a lot of scales, minor technique tweaks, memorization, and, yes, practice. Real, honest-to-goodness practice. My favorite feature in Rocksmith is the Guitarcade, a series of minigames dedicated to improving those technical chops that are sleep-inducing to practice by themselves. Like Typing of the Dead, the Guitarcade games mimic established game genres to reinforce and practice certain skills. There’s the autorunner-esque Gone Wailin’!, which helps you learn to control how hard you’re strumming; the Double Dragon send up Scale Warriors, which makes you fight thugs by playing scales of increasing difficulty and speed; and, of course, Return to Castle Chordead, a ham-fisted first-person love letter to Typing of the Dead where you shoot zombies by playing guitar chords. But the best part about these minigames—and learning in Rocksmith generally—is that they don’t allow you to look at the guitar while you practice. I found that some of the most dramatic improvements I made playing Rocksmith came from my new independence from looking down at the guitar to check which fret I was on when.

If you have a guitar that doesn’t get enough love, Rocksmith might be the perfect way to rekindle an old flame. Beginners should be aware of how high the mountain is that Rocksmith suggests they climb, but it will sherpa you along every step of the way, even if that sometimes means climbing the same part over and over and over and over and over.