Rooftop Cop investigates the "ritual manifestations" of police violence

At what point does a cop become a threat to the subject they’re supposed to protect?

That’s a very loaded question. One that probably sent your mind reeling with headlines and photographs from the past year; it was a good one for disputing the actions of authority. It’s a question that Stephen Lawrence Clark’s MFA Thesis for his course in Game Design at NYU Tisch dives into. It’s a videogame called Rooftop Cop that consists of five vignettes and a 7-track album, all of which are based upon a “loose metaphysical timeline in which the Cops slowly lose their way.”

feeling like you’re making up crimes in order to meet a quota

Clark proposes that, for the most part, upholding the law is performing a sequence of rituals. Routine patrols, arrest procedures, witness protection, crowd control—it’s all outlined step-by-step by the jurisdiction and carried out by enforcers (or it’s supposed to be). He compares this institutionalized behavior to wobbly scaffolding, in that it elevates cops to feel important despite the structure they base their actions on being “built up over time by malcontents and rules-abusers.”

He arrived at these thoughts after reaching the moment in thecatamites’s game Crime Zone in which there’s a “drooling sense of warmth and community” as cops look over a city from various rooftops. He was enraptured by the idea of a “police cult”, which is given all this power to perform across a number of weird rituals, and also the “communal self-assurance” that comes with it that aims to justify any police action, questionable or not.

Hence, the five endless vignettes of Rooftop Cop are attempts—not all as successful as one another—to present police behavior as “ritual manifestations” of violence. Clark divides this violence: political, environmental, personal, temporal, and non-violence.

The first vignette titled “A Proud History” is the purest and easiest to read as a text. You’re presented two sets of numbers: one representing the “enforcement coffer”, the other is the “director’s coffer.” Your aim as a cop is to transfer the director’s coffer over to the enforcement coffer. To do this you need to pass the numbers through citizens strolling around the city. You click on a pedestrian and the number builds up, as if you were placing a criminal charge upon them—a literal number on their head—except, no one is actually committing any crime.

He asks us all to scrutinize where we place our values

It ends up feeling like you’re making up crimes in order to meet a quota (perhaps the number of required arrests per month) as demanded by the institution. The final act of transferring the number on the citizens’ heads to the enforcement coffer is killing them in bloody murder. There are no consequences for this as you have justified the act with your criminal charges. All the while, your cop buddies look down upon you from the rooftops. Eventually, the entire population has been murdered and only the cops remain.

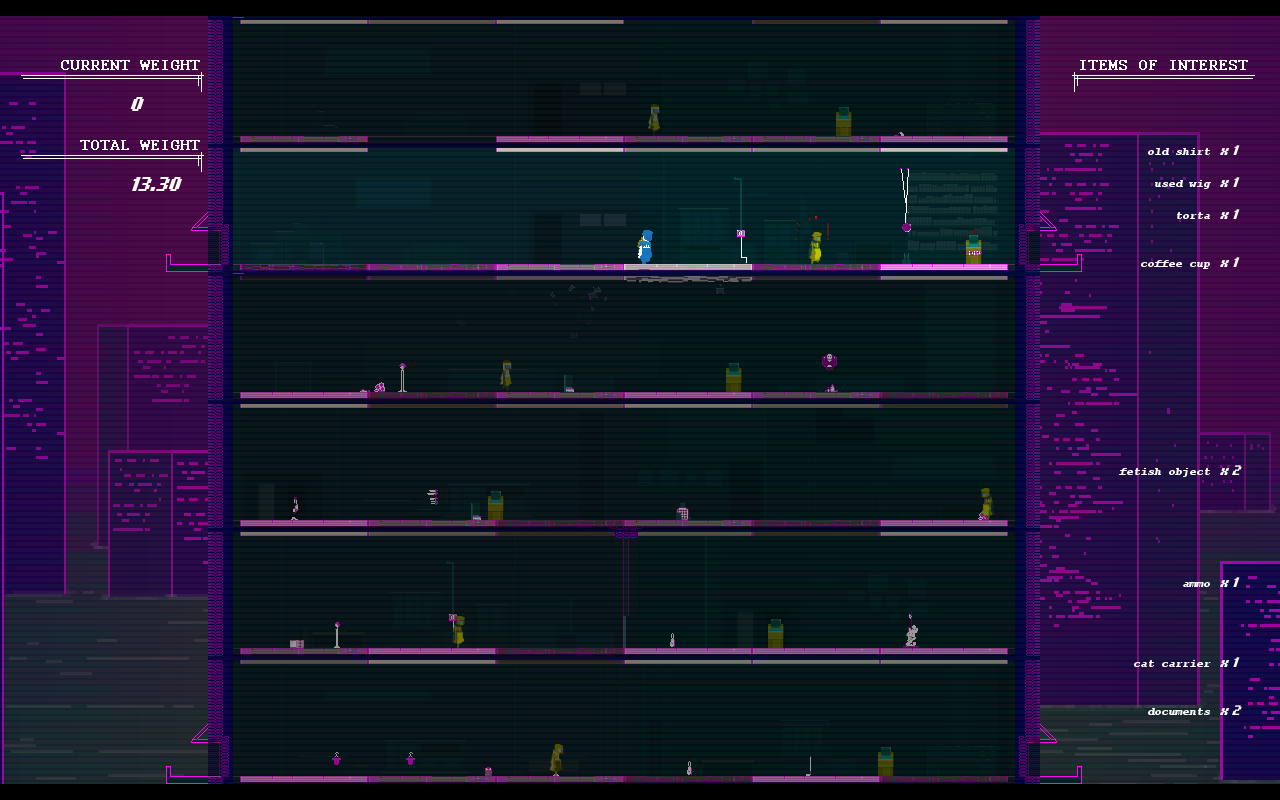

The four other vignettes of Rooftop Cop abstract further into this dystopian mindset. For me, two of these work better conceptually and in play than the others. “The Datamines” has you barging into the homes of a multi-tiered tower block to gather evidence before you can be caught for your intrusion. Fill your thieving sack of evidence up too much, however, and you’ll be crushed under the weight of it.

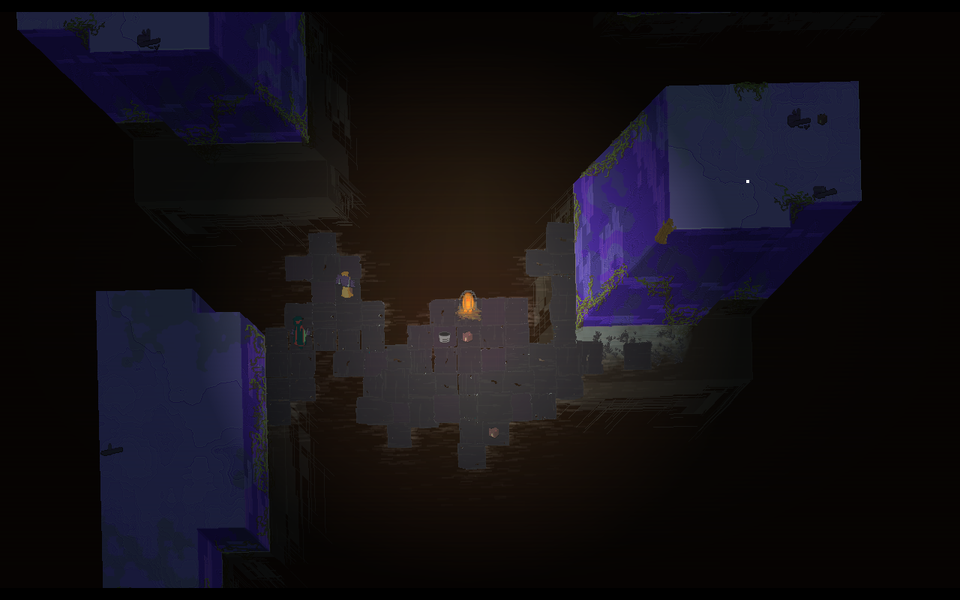

“God Bles Everyone” seems to be a more direct recreation of the “wobbly scaffolding” idea. You travel down a river, building and rebuilding a barge out of debris. You can pick up extra cops from nearby rooftops if the barge reaches out far enough. The same buildings you pick them up from also destroy parts of the barge if its shape becomes too large.

Although Rooftop Cop targets a specific institution, Clark sees it as an invitation for us to critique ourselves as much as the authority in our lives. He reflects on how his fond, formative memories are built around dehumanizing industries and cultures (“Pizza Huts and Walmart parking lots, and Marathon Oil Company cook-outs.”).

He asks us all to scrutinize where we place our values and to question whether or not the actions they determine for us are, in fact, more damaging to humanity and the environment than it’s worth.

You can purchase Rooftop Cop for $5 along with the game’s soundtrack on itch.io.