Rudyard Kipling’s classic novel Kim is now a videogame too

Rudyard Kipling is a complicated figure. On the one hand, you have the arch-colonialist, the author of the poem “The White Man’s Burden,” and an all-around fan of Empire and the progress it supposedly represented. The man who spoke of subjected populations as “Half-devil and half-child,” and celebrated the bloody project of colonialism as a way to uplift the natives of India, the Philippines, and Africa to (British) civilization.

But then there’s Kim (1901), the story of a young British orphan raised as an Indian native. At once a children’s story, a travel narrative, and a genuine work of joy in its 19th-century cultural landscape, the novel delights in the sheer variety of that part of the world—where Muslims, Jains, Hindus, and Buddhists intersect not merely as colonized subjects, but as people. Indeed, the book has perspectives rare in the 19th century, as when, say, an Anglican clergyman’s partisanship is critically exposed: “Bennett looked at him with the triple-ringed uninterest of the creed that lumps nine-tenths of the world under the title of ‘heathen’.” In short, it is a complicated text, especially when viewed in relation to its arch-colonialist author.

the more adult problems of the world remain just out of view

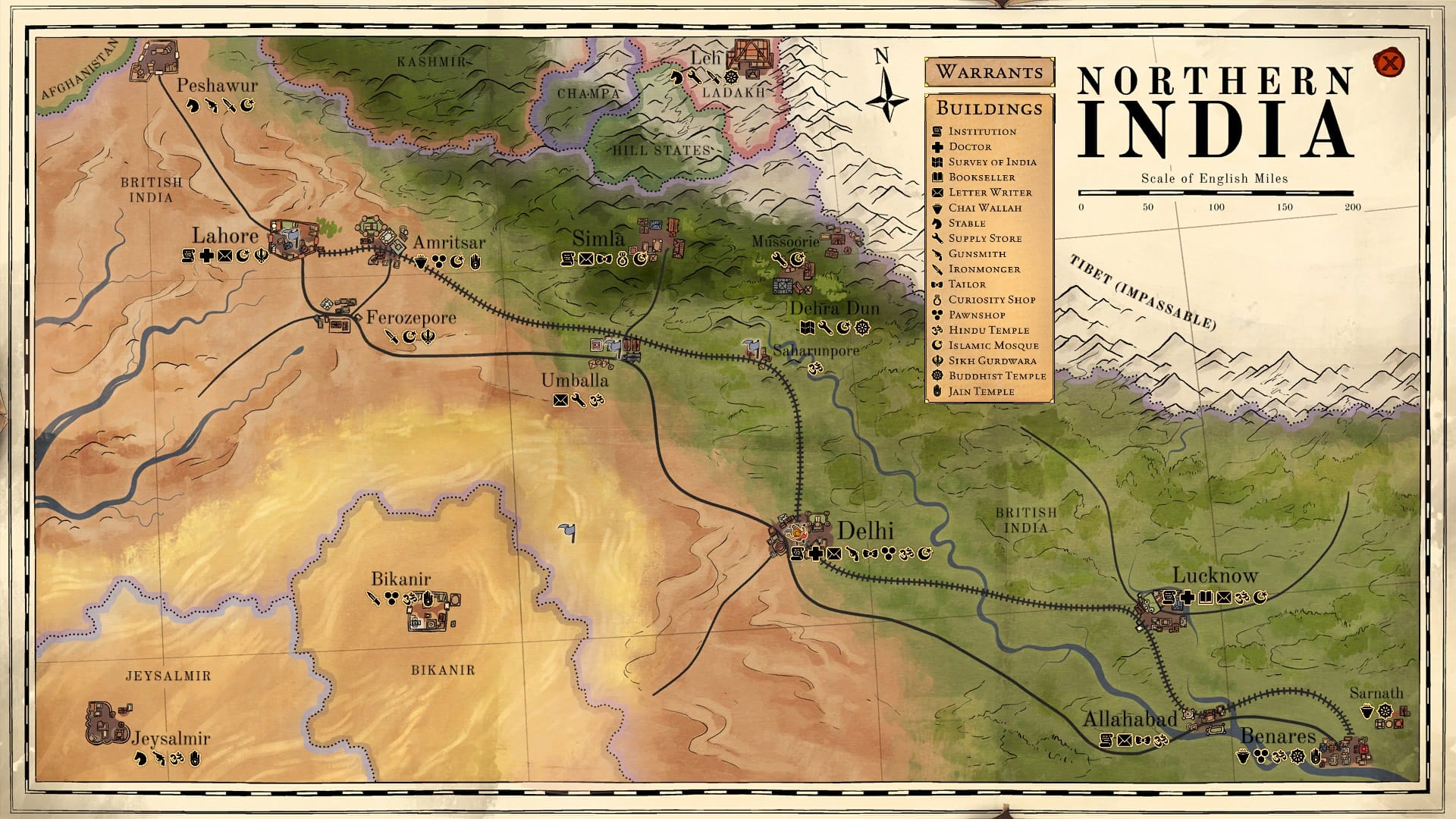

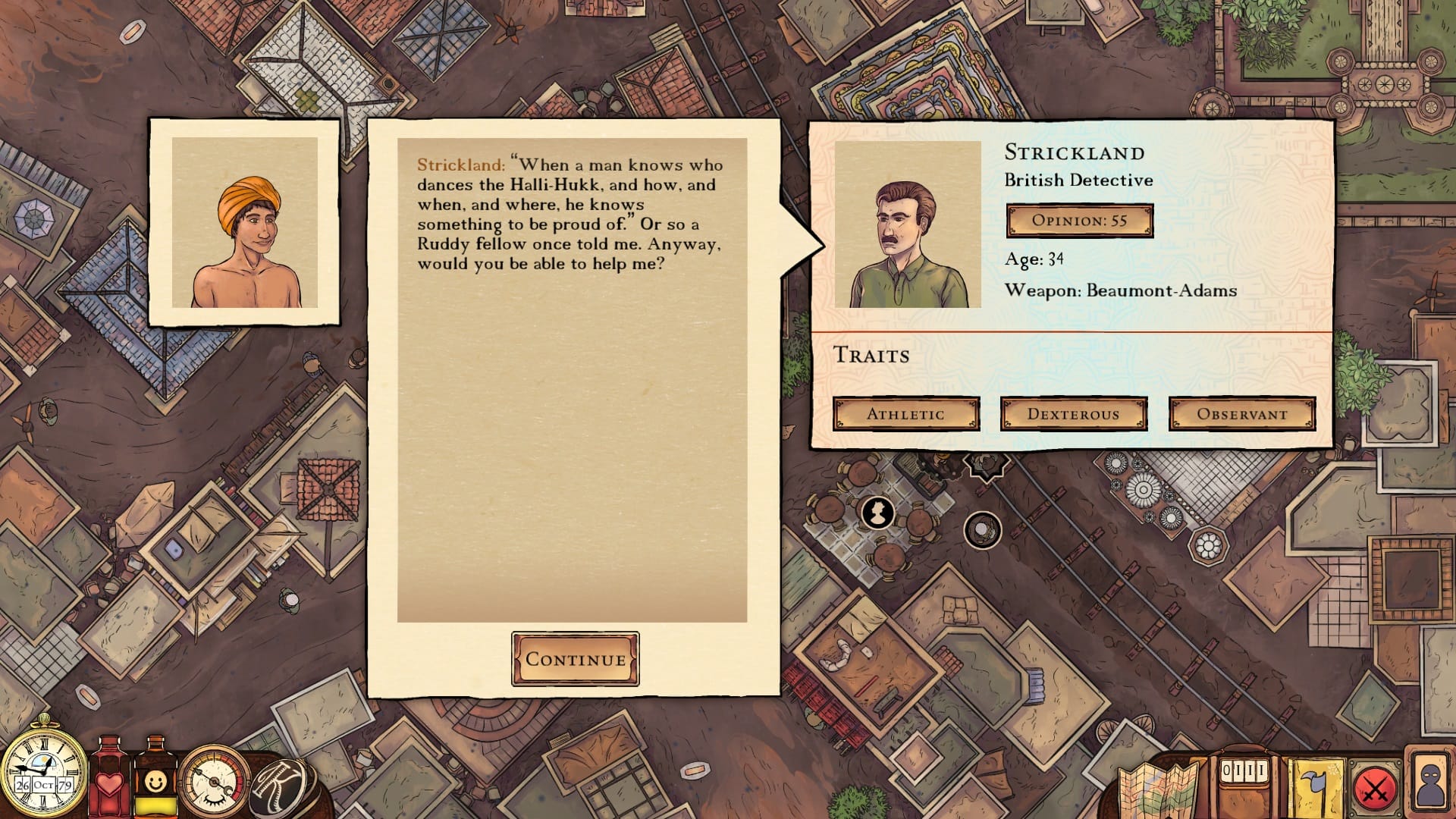

Now Kim has been made into a videogame by the Secret Games Company. It’s been realized as a top-down roguelike that has you wandering from Lahore to Allahabad, to Delhi and back again, across a vividly colored, hand-painted-style terrain. The player has three years to simply wander before Kim reaches manhood and the game ends. This involves jaunting along the same railway network that contributed to famines (where any grain from famine-struck areas could easily be shipped away from those who needed it), and through cities whose rebellions and uprisings are still recent history. But the cities are bright, beautiful, and new to a native of Lahore—and this vivid, childlike world is the great joy that Kipling and, in their turn, The Secret Games Company are trying to show you.

{"@context":"http:\/\/schema.org\/","@id":"https:\/\/killscreen.com\/previously\/articles\/rudyard-kiplings-classic-novel-kim-now-videogame\/#arve-youtube-1u_prqyica4","type":"VideoObject","embedURL":"https:\/\/www.youtube-nocookie.com\/embed\/1u_prQyIca4?feature=oembed&iv_load_policy=3&modestbranding=1&rel=0&autohide=1&playsinline=0&autoplay=0"}

This adolescence is the game’s main draw and its saving grace: Kim is a child, and the more adult problems of the world remain just out of view. There is only a brighter, kinder world that remains visible as you travel from town to town with a Buddhist Lama and a childlike indulgence in the minuteness of the moment, and not the bloody scope of history. Kim, the novel, works as a piece of children’s literature because of this focus; Kim, the videogame, tries to bring that focus to the experience of the road: “Roads were meant to be walked upon, houses to be lived in, cattle to be driven, fields to be tilled, and men and women to be talked to. They were all real and true—solidly planted upon the feet—perfectly comprehensible—clay of his clay, neither more nor less.”

In short, Kim—both the novel and, to its credit, the game—reminds me of this: when I was 16, I went to India with my mother and my uncle. We spent a few days in Darjeeling, a town in the North-Eastern part of the country, where the eponymous tea is grown, and stayed at a colonial-style hotel called the Windemere. One evening, two other guests played Gilbert and Sullivan songs on the hotel’s out-of-tune piano. Outside, down the slope of the hills grew Darjeeling tea; beyond was the mountain Kangchenjunga, which would remain perpetually visible as we moved further into Sikkim. Even as I grew older and my knowledge of the dark weight that these things carried grew, it did not stop being beautiful.

The full versions of Kim is available for Windows and Mac on Steam as of October 24.