Rui Hu: The infinite futures of games

Can games predict the future? Rui Hu works across still images, film, CGI, game design, and physical installation to examine decision-making processes, the unfolding of time, and the independent course memory seems to take. The Guangzhou-based artist takes inspiration from video game culture and real-world events to create thought-provoking work that’s at once ultra-serious and exhibiting a satirical edge. Currently, he is an Assistant Professor of Practice in Computational Media and Arts at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

Here, we speak with Rui about the educational power of a game play-through, why instant noodles feature prominently across his projects, and why games are definitively a time-based medium.

[Content warning: this article mentions art pieces that utilize imagery of school shootings]

Can you talk about the environment you grew up in, and how it helped propel you into the creative sphere?

I grew up in the city of Guangzhou in the southern part of China. It was a large and populated city, but my family lived in a remote region of the city surrounded by mountains. My mom loves to buy me books, mostly novels, and a lot of them were in translation. I wasn’t out to play much.

When I was a small kid, my dad brought back home a super old retired computer from his workplace. I started playing with it— from what I remembered, it was probably a pirated DOS system. They installed a lot of strange things on there—it had a Chinese user interface so you don’t have to type in all the English commands to operate it. Of course, my time spent with the computer was super limited. I had one hour every day. That’s super short when you’re a kid—you get halfway through the game and then it’s like, “Oh, time’s up.”

I read that you were interacting with game worlds first through walkthroughs.

I’m a really slow player. Some people can just bang their way through the game and just maybe finish it in… I have to go online and look up information. And if there’s an adventure game, I try to go through all the other routes.

I remember playing Silent Hill. But when I was playing the game, I had to open all the doors. And even after I had found the item or the key for me to move on to the next thing, I still have this compulsion to still stay in the current area and finish all the un-open doors. So I’m a really slow player in that sense. Later on I wasn’t able to do that person myself because it just took too much time. I would go on YouTube and look at gameplay footage, and also look at commentaries that the YouTubers post.

Busy people don’t have time to read books, so there are services that give one minute summaries. In the same way, play-throughs gave me a pretty concise way for me to understand a game and how people think of it.

You went to film school for undergrad. How did you begin to create inside game engines?

At first, I wanted to go into literature. For two years, I studied Chinese Literature and thought I would work as maybe a writer or something. I did a lot of writing—mostly fragments to build character, but then also some poetry. Not very prolific, but I still made a habit of it.

I got a bit bored by the teaching style in the university that I went to, and also at a time I started watching a lot of movies and especially European arthouse films—Antonioni, films like that. You weren’t allowed to transfer majors in China at the time, so I did a year of community college in Santa Monica, and then I went onto NYU and finished in the Film and TV department. In New York, I visited a lot of galleries, but the filmmaking models they taught in undergraduate at NYU— they are all in this independent tradition, but still the very traditional modes of filmmaking. I would help out with a friend’s shoot, but if you’re in a non-essential role, I’d go to the set, help set up the scene, and then stay there for an entire day without doing anything else meaningful.

I got into animation because that’s something that I could do myself—but I wasn’t really good at drawing. 3D animation allowed me to both work artistically, but also I can complete everything by myself. There are 3D models I can download from the internet. I realized it was the best way to both make moving images and also have it have something to do with video games as well. It’s a language that I’m familiar with. In film school, I started doing a lot of 3D animation and also visited a lot of art exhibitions, so my work at that time has been moving more towards more personal.

I learned about a program at UCLA called Design Media Arts. Our neighbors were the Fine Art department and the Architecture department. People in our program did more art with technology—computer programming and then 3D graphics, electronics. At UCLA, I realized that the video game engine was actually something that can be used to make personal artistic work. Also, at NYU, I had to occupy a whole computer lab to do my 3D renderings. I realized the video game engine would be a much more efficient way to do that.

You’re interested in decision-making processes and blending the past and the future into the same space. Do you feel like you have more control over time in a game engine versus a more traditional film?

That question has always been there if you study film or animation. You can have one shot that lasts for 10 seconds, but then maybe only one second in the story takes place within that animated world. Animators have found a way to compress time and to tell a story that can span millions of years and in a two hour movie.

In games, you have this idea of real-time. The game progresses and your running speed tries to mimic the real world—it has this completely artificial, fabricated constraints put on the player to try to mimic the physical world. It intrigues me so much that you have complete freedom in the game engine—but then, people try to mimic the physical world, and then there are all these constraints.

When we talk about time-based media, usually we use that to refer to film or animation video—it’s something that you can replay. But I’ve started to think, have people been using time-based media to describe video games?

If we do, then it’s a completely different kind of time—the event or the progress you made in that specific game is in sync with the physical time that you spend with. Games are a time-based medium in the sense that the passes in physical world. So if you haven’t progressed in the game, then the action never actually happened. It has happened in the system—in the sense that the game has been designed. But that specific play-through would never have happened if the player doesn’t play it personally. A game is unlike a film where if it’s been made, then regardless of if you watched it, it’s always there.

For the project Would you Help Me to Carry the Stone, what invention were you hoping to make in the overall conversation about first-person shooter games and memory?

My feeling towards that project is a little complicated—it has gone through multiple iterations. I first had this idea in 2017. The main component of my thesis project at UCLA was actually not this game but a series of still images. In the exhibition, they would be printed out and hang on a wall, more like a traditional photo. The idea was that the virtual world infiltrates the physical world. I thought about how things from the internet or from games, they reach out of the screen and make an impact on the physical world.

For Would you Help Me to Carry the Stone, I read about the school shooting event in the U.S in Sandy Hook, Connecticut. It was a big, very tragic event. I was reading the local prosecutor’s report and it spent a large portion describing his love for shooter video games, describing his daily routines, how much time he visited the local arcade and played video games, and what’s his video game collection at his house. The conclusion was that his favorite game was Super Mario Brothers and Dance Dance Revolution, so a lot of the non-violent games, ones that anyone can play. I found it intriguing because obviously it went into details about that description of the shooter—his video game habits purposefully. There was a certain assumption being made, and then also based on maybe the media discussion about games and violence around that time, so then they decided to include that. But the conclusion wasn’t pointing to video game as part of the main driving force.

I was just an international student at the time. I wanted to talk about this event, but I wasn’t sure how. As an outsider, it’s almost like I was pointing fingers at some of the things that’s happening in the United States. And that didn’t quite feel right. It took a long time for me to make this project.

My idea was about the idea of being trapped by life circumstances—because video games are often seen as escapist. You have things hard to deal with in life, but you try to gain a feeling of achievement in video games. The project incorporated a storyline into the game. The character is waiting for their friends to come play games in a video game motel. They have these motels in China where you can spend the night with friends there and then they have beds, but also four computers in a room.

His friends never show up, so he goes on a quest to find them. He discovers that they are being trapped here by a mysterious boss. I decided to translate the project into a video, where I incorporated all the play-through videos of that video game, and added dialogues, texts, and other source material.

A lot of your projects in the way that you incorporate the virtual world into the physical installation. Do you find any difficulties moving from the digital into the physical?

Making Would You Help Me to Carry the Stone, the whole process was really suited for this kind of translation. When I make a work, I always think about this idea of ‘lore objects,’ objects that tell a story or have an emotional attachment to them. I was very selective in terms of what I put into the game, which made the process much easier because anything had a particular reason for existing in the game.

Choosing what to bring out of the virtual world into the physical exhibition became more of a process dictated by how the objects look, but also about how they fit into that environment. Last year, I showed that project in the basement of a museum, M WOODS 798 in Beijing. The basement was originally designed to be a nightclub space, so it was not a traditional white wall gallery space. They also had these neon lights that are in the cement wall, very industrial.

I used iron tubes that form the main structure of the virtual environment. They form a structure that can be seen as both protective—a pyramid shape that’s almost a protective structure—but also invasive, in the way the shape is aggressive. Also, there are elements from the video game that I made in the physical space: the first aid kits, and the Coca-Cola cans hung on the same wire. The first aid kits are common in shooter games or war games. The first aid kit—something that’s supposed to save your life or help you cure wounds—and then the cola cans on the other end. They’re both red, this idea of emergency and blood, versus the red on the consumer product that’s meant to catch your attention and stand out on the shelf in the supermarket.

On the floor, I had a Dance Dance Revolution pattern. The arrows on the ground point you towards all these different directions, which means nothing almost. In the Sandy Hook case that I mentioned, the shooter would spend hours playing DDR. I remember the report describing him as energetic when he played this. You perform well in Dance Dance Revolution by following instructions. Whatever the game or the music or beats tell you to step on, you step on that spot. Also, arrows reference the mouse cursor. There are blocks in the game environment made of the shape of the mouse cursor; that actually form a path for the character to follow. You have many arrows telling you where to go, but then the environment traps you.

How did your latest project, Soon It Will Be Deep Enough, come to be?

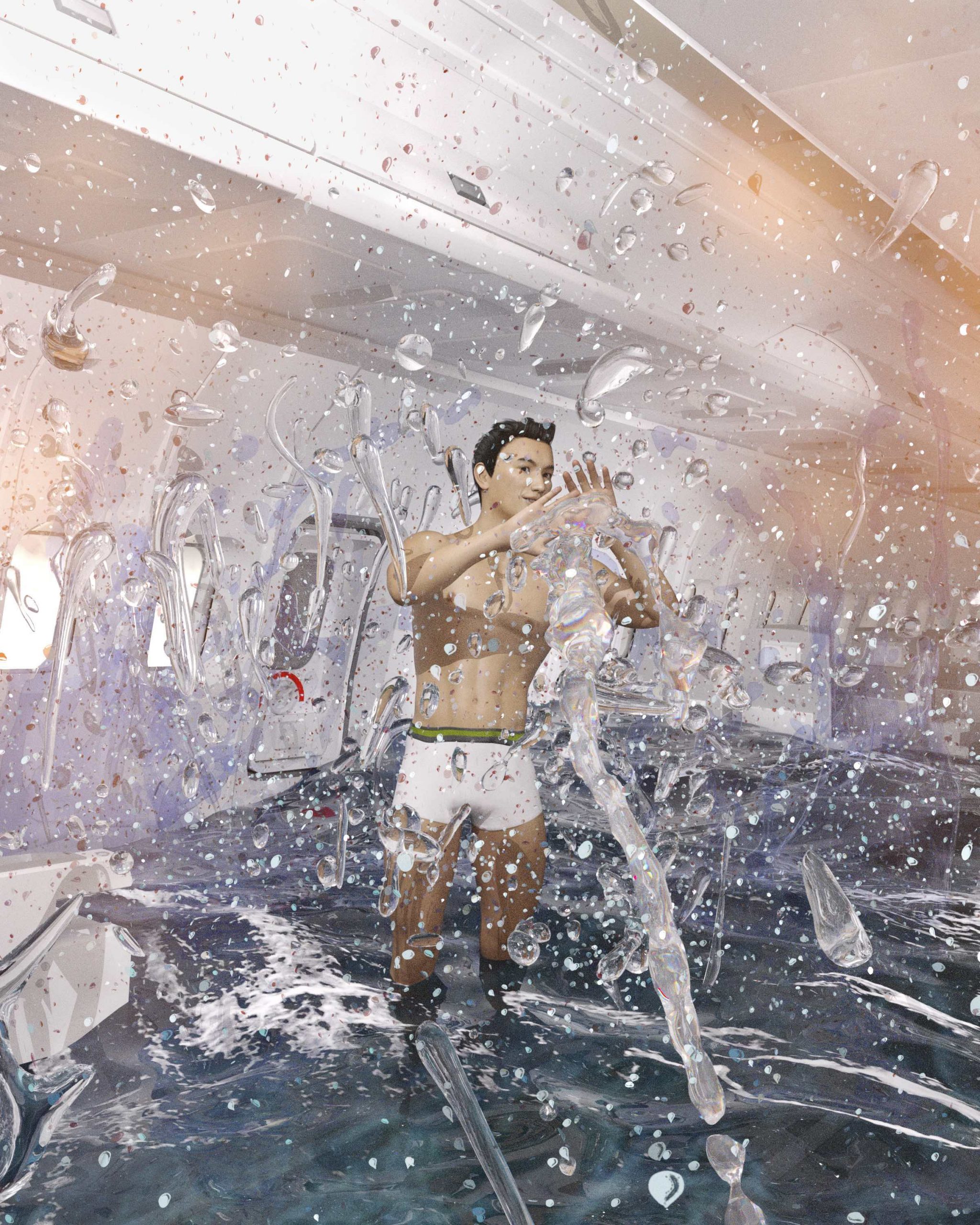

From 2017 to 2018, I finished grad school and was trying to find work to do. I had been reading articles about climate change and the rising sea level. Also around that time, Los Angeles residents experienced what had been one of the most serious wildfires in recent years. The orange tint of the sky gave the city a doomsday feel. Around that time, an art project platform called Slime Engine, run by four young artists in Shanghai, approached me for a new work—the theme was about airplanes. I also had frequent thoughts about potential plane crashes when taking flights across the Pacific Ocean, made worse by the news of Boeing 737 Max accidents around that time. A lot of things added to the anxiety. But Los Angeles always has a pool party scene and beach culture. I wasn’t able to get the fun from it but was certainly influenced by it. Soon It Will Be Deep Enough is both a party and a disaster.

The installation of the work at AM Art Space in Shanghai was thought of as an extension of the video work. Nothing in the physical elements were seen in the video, but instead trying to create extra layers of experience or meaning. For example, the wall where the screen was hung was covered entirely by plastic grills, which is a material often used around the edge of swimming pools. There was also an inflatable slide installed on a staircase in the gallery space marked with the word “SOON.” The slide is also meant to be ambiguous and could be two contrasting things, just like the video; it can be either a slide used in a waterpark, or a slide used for emergency escape from an airplane.

Credits

Edited and condensed for clarity. Interview conducted in February 2021. Photography courtesy of Rui Hu.