Salt and Sanctuary has soul

Salt is an essential part of our biology. It helps regulate fluid balance between cells. Our entire system of nerves and muscles is designed around the special electrochemical properties of salt. Too much salt and we die. Too little salt and we die. It’s the perfect metaphor for the kind of complex equilibrium Salt and Sanctuary likes to brutally enforce. Get too aggressive and you die. Give into cautious hesitation and you die. Learn to navigate the invisible rhythms in-between these two extremes, though, and something beautiful happens.

It’s a construct familiar to anyone who’s subjected themselves to the punishing specificity of a FromSoftware game. This is why it’s impossible to talk about Ska Studios’ Salt and Sanctuary without mentioning the Souls series. But it’s also unfortunate, because comparisons like this are more likely to bury the former under a pile of decomposing clichés than unearth its unique merits.

Yes, Salt and Sanctuary treats salt like a currency that can be collected from enemies and invested in leveling up or weapon upgrades. And yes, you can lose all your salt for good if you die in the field and are unable to collect your remains before dying again. Players can choose from a number of classes, ranging from vanilla fighters to poison-immune chefs, but a sprawling skill tree lets them customize their character from there. Most Souls-ian of all, every action is constrained by a stamina bar which, though it can be expanded over the course of the game, is always finite.

Calling Salt and Sanctuary a 2D Souls game, however, is like saying a map is just a picture of reality if it were in two-dimensions instead of three. That people spent centuries debating whether the Earth was flat offers some indication that the problem is more complex. As a gothic, side-scrolling brawler, Salt and Sanctuary relies on the friction of blood and bones in compact spaces to create forward momentum. Propelling the player up and down a series of bi-directional boulevards, the game owes more to SNES-era platformers than FromSoftware’s recent empire of action-RPGs.

Loosely tasked with finding a princess so that her marriage to a prince can cement peace throughout the land, Salt and Sanctuary begins in earnest when you awaken on a color-drained beach with only one way forward. Like the beginning of Playdead’s Limbo (2010), the game feeds off the player’s instinct to scroll from left to right across the screen with her bewildered avatar. Contrary to the taunting aimlessness of Souls, Salt and Sanctuary is urgent and direct.

the savage violence moves beyond life and death to take on a vivacious quality

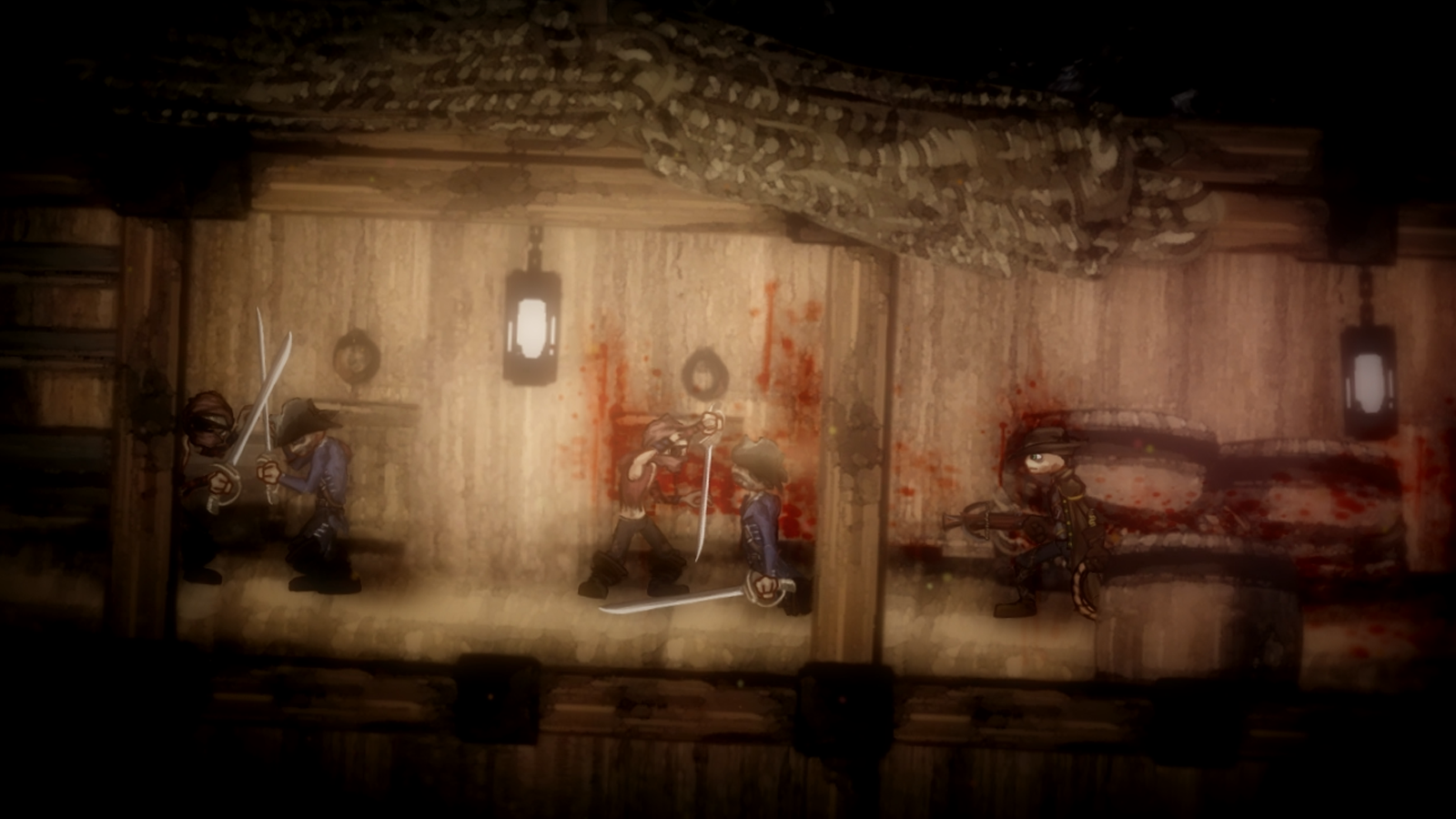

It’s less interested in meticulously deconstructing the player, one deathblow at a time, instead reveling in its crunchy sound effects and scintillating blood splatters. Mutant blobs that try to suffocate you explode once you break free. Flames pour out of the necks of Hyena-looking reptiles when you decapitate them. Bones crackle and hiss whenever you smash something that looks even remotely like it might have a spine. Knock an enemy down and rush to its side fast enough, and the game will prompt you to curbstomp the remaining life out of it.

These aesthetic flourishes are what tie the game together and make it feel so bouncy and full of life despite its macabre trappings. The desperation of my grizzly, white-haired sorcerer as he dodged and hewed his way across the screen became a source of inspiration rather than soul-crushing fatalism. In two dimensions, the contours of a hitbox are laid bare, and the enemy’s tells have nowhere to hide. By abstracting reality and rendering it more pure and cartoonish, the savage violence moves beyond life and death to take on a vivacious quality.

The common Souls encounter has the feel of two entities wrestling in the mud to see who can extinguish the other first. Understated given the stakes, it has all the charm of Nicolas Winding Refn’s Valhalla Rising (2009), which is to say none. Refn’s viking pilgrims know only the hell of Dark Ages Europe and its daily immiserations of the flesh. What they lack in charm, however, they make up for in the pity they provoke when confronted with a life that’s nasty, brutish, and short. Salt and Sanctuary instead captures the driving force of Gareth Evans more jubilant The Raid: Redemption (2011). Death at the bottom of the apartment block is not the same as death at the top or beyond, providing the film with a clear trajectory, both moral and physical, against which to measure progress. When Evans stages a scrum between gang members and swat officers, its fury and delight is underlined by clear objectives rather than sadistic absurdities. Salt and Sanctuary is content to teach you how to move through hell without the need to torture while you search for the exits.

The game’s use of “brands,” platforming abilities bestowed by NPCs dispersed throughout the world, show Salt and Sanctuary’s substantively different focus as well. Beginning with a vertigo brand that allows the player to flip gravity at specific points and walk along the ceiling, each one offers a new way to traverse the game’s labyrinth and access previously gated areas. With many of them doubling as combat maneuvers, like a wall jump and air dash, the player’s relationship to the world around her becomes deeper and more intimate.

What begins as a weighty trudge through the festering underbelly of dark forests and abandoned keeps slowly evolves, growing lighter and more nuanced and intuitive. The overall effect is one of relief and, eventually, transcendence. Instead of surviving Salt and Sanctuary’s horrors by obsessively dissecting them, liberation comes as a result of being able to execute ever more deft acrobatics with a few simple twitches. In this way, the game helps us learn to shed the burden of realism by flattening it, reducing its physical and emotional details into obstacles that can be overcome with the flick of a button.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.