Second Quest’s rejection of binary ritual

David Hellman taught me to draw. More than a decade ago it was his diligent digital brushstrokes, revealing and obscuring light and shadow, shaving lines into recognizable forms, that I first copied. If you look at his early webcomics on A Lesson is Learned but the Damage is Irreversible you can see how, rather than clean lines, his images are made of innumerable overlaid strokes. It’s those little floating specks that give him away, remnants of an underlayer left uncovered by the constant reshaping of forms. Studying his and Dale Beran’s comics I learnt that drawing digitally can be a kind of infinite sculpture, spaces hollowed out in a hypnotic ritual of light and dark.

I don’t remember how I first came across A Lesson is Learned, but its tiny forums became the center point of the internet for a short portion of my life. I would hang around with friends both local and global, idly waiting months for the next ambiguous comic, ready to pick it apart and see what mysteries it held. A friend and I had our own webcomic, with an equally erratic update schedule. Like A Lesson is Learned, it was mostly an excuse to draw fantastic worlds while still looping them into everyday life. To resolve the binary of fantasy and reality that never felt so strong for those growing up in virtual worlds.

even the simplest of stories can carry a thousand shades of meaning

Second Quest is born of that same intention. A collaboration between Hellman and the writer Tevis Thompson that emerged from his essay Saving Zelda, it turns its attention to Nintendo’s timeworn series in order to reimagine the world of Deku trees and Rupees as a space of both relevance and mystery. Taking 2011’s Skyward Sword as its framework, it shuffles, reconfigures and transforms the constituent pieces of the Zelda mythos. In its simplest form, the result is a challenge, not a critique—a call to arms by an artist and a writer who desire to see the games they play match their values. But Second Quest is also more complex than that. It is an exploration of how even the simplest of stories can carry a thousand shades of meaning.

///

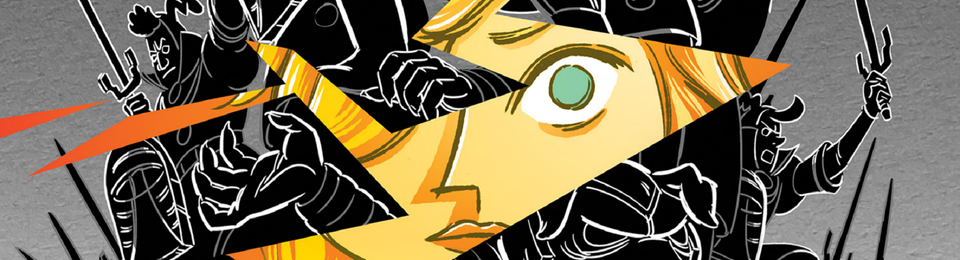

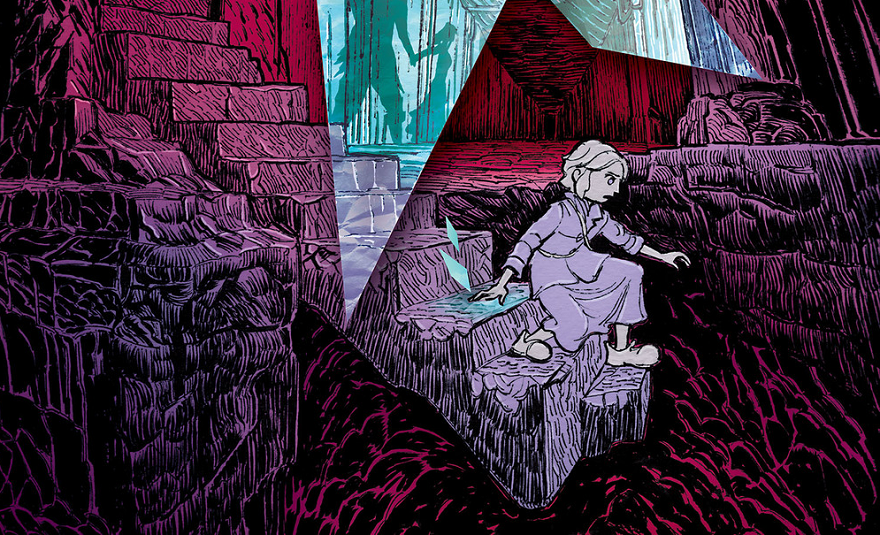

David Hellman’s work has gathered years’ worth of sophistication since A Lesson is Learned. In Second Quest his drawings run freely across the page, filling corners with repetitive patterns of curlicues and clouds, coloring everything in unlikely hues of luminous light. His work has always seemed more comfortable depicting lost dreams, unlikely futures and alternate realities than everyday life, and here it feels the most at home. Second Quest is the story of Azalea, a near anagram of Zelda, and her journey of self discovery. Living high above the clouds on a floating island, she is part of an insular society, broken off from the world below and its dangers. Despite this isolation, she carries an unquenchable curiosity about the world around her, and a gift for seeing that which is lost. Her home has a secret, a history that it has chosen to forget. Second Quest, at first, reads like the opening to a thousand fantasy stories, from JRPGs like Golden Sun to the hero’s quests contained within The Hobbit and His Dark Materials. A hero, a gift and an event which changes their world forever. With its beautiful drawings and halcyon tone, Second Quest’s opening feels like slipping into a warm pool of familiar ideas, ones that extend down well-trodden paths. Of course, Thompson and Hellman’s references are also cribbed from Zelda—with keys, caves and a chest full of items, including a boomerang, a catapult, and, of course, an ocarina.

This, along with an early image of Azalea in her room from above, the forced perspective instantly recognizable, gives the initial impression that Second Quest borders on rose-tinted fan fiction, an insular celebration of a set of popular signifiers. Yet this would be to underestimate the significant changes Thompson and Hellman feed into the franchise. Only pages after they present their chestful of Zelda artifacts, they begin to pick at the foundations of the Zelda myth. A classroom recitation of an old story becomes something much more unsettling, an indoctrination. Children are asked to repeat the story of the pig thief, kidnapper of the Vessel, the sacred woman so dearly loved by her people. The Vessel had to be saved. Yet Azalea, beset by conflicting visions, asks “But what about her? What did she want?” The teacher responds, “She wanted to be saved,” but the seeds of doubt are already sown. It is this inquisitive mind that Second Quest aims to turn towards the series that inspired it. What about Zelda? it asks. What did she want?

///

There are two sides to every story. That’s the way the old cliche goes. In the case of the Zelda series you might say there are three. The triforce is what gives us those three elements: Link symbolized by the triforce of courage, Zelda symbolized by the triforce of wisdom, Ganon symbolized by the triforce of power. Yet that’s not how it has always been. In the first entry in the series, 1986’s Legend of Zelda, there were only two triforces: The triforce of power and the triforce of wisdom. Ganon possessed one, and Zelda split the other into eight pieces in order to hide it from him. It is as if the world of Hyrule was split between the two poles of thought and action. Between these two poles lies Link, the boy hero who is chosen to seek out the pieces and unite the two. This arrangement seems to have left a legacy throughout the series. There’s a binary nature to every Zelda game, an interplay of good and evil, light and dark, male and female that runs through its stories. It’s a simple ritualized story, one that is transformed with each game, but always falls into familiar patterns, split down the middle.

This status quo is the true antagonist of Second Quest

Second Quest takes its name from a feature in the original Legend of Zelda that saw enemies, bosses and dungeons rearranged to make the game harder. A secret of sorts, it was made available to the player after they completed the game for the first time. Yet this is not the only way to trigger the second quest. It can also be played at any time, if the player simply names her hero Zelda. It may be little more than a cheat code in the original game, but Thompson and Hellman seem to be interested in reimagining this renaming as an act of great significance: Zelda as the hero. There’s a certain sense to this, after all. The Legend of Zelda’s binary is not constructed around the hero and the villain, but wisdom and power. Zelda and Ganon.

However, over the years this binary relationship has become something of a fixed position for the Zelda series. Apart from a few exceptions the characters have, by the time their credits roll, fallen into their old roles. There’s a sense of comfort to this, the idea that there will always be a Zelda and a Ganon, you just have to find them. This is the comfort that the society of Second Quest trades in. For them, the binaries of good and evil, dark and shadow are ways in which to keep their worldview firmly in place. The quest narrative is something they have turned into an endless ritual, one which returns again and again in the form of an ornate ceremony. It’s a process that turns ideology into storytelling, justifying suspicion, fear and arrogance. This status quo is the true antagonist of Second Quest—not evil, but an unthinking adherence to ritual. In some ways this is the accusation Hellman and Thompson make towards the Zelda series, that its pursuit of binary rituals and familiar refrains over mystery and adventure have atrophied its vocabulary. But it is also an accusation they level at the wider world. Hellman and Thompson, however humbly, begin a process of questioning our stories themselves, and how they affect us in hidden ways.

///

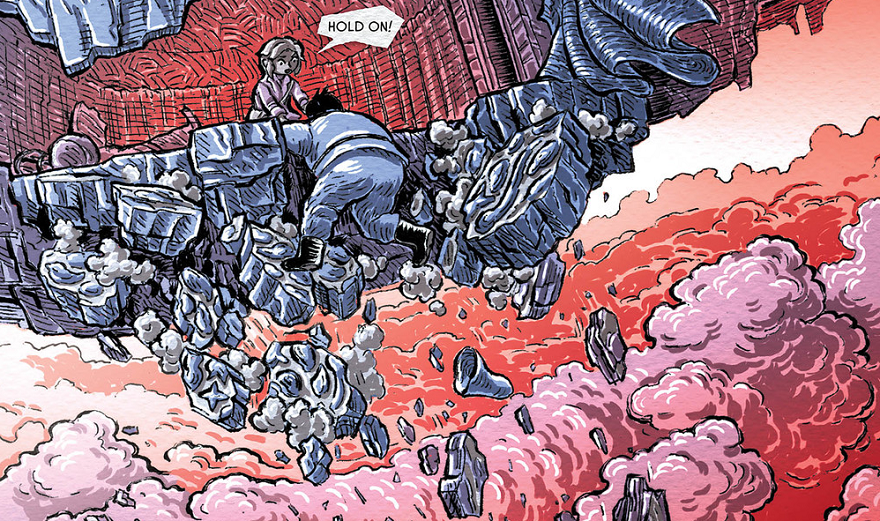

Quest myths are almost ubiquitous in cultures. Long-held stories of ancient battles that are intoned into society again and again with each generation. I certainly wouldn’t be the first person to suggest that a recent obsession with superheroes in the West is a continuation of this practice. Quest myths are equally present in videogames, their simple structures and clear motivations ideal for driving simple interaction. The Legend of Zelda was one such game, its barebones story laid out in its instruction manual. Yet it had something that most literary or oral myths do not: secrets. Hidden on each screen, behind illusory walls or under bushes. It is these secrets that captured Thompson and Hellman’s imaginations. Not the story of a princess and a thief, but the possibility of a world full of stories, a horizon littered with mysteries, and no set way to follow. Second Quest offers a similar horizon, an unfinished story marked by choice, not circumstance. It sees legends as they have always been: a way to fill the world with stories, not to control it with them.

Second Quest is ultimately a work of optimism. It takes the idea of the hero’s quest and rejects it, choosing emancipation over adherence to prophecy. It promotes a new way of looking at myth, and the potential of doing more than just going along with the story. Azalea, the hero of Second Quest, is offered the chance to become Zelda. She is shown a life of ritual, of waiting, of service. She is shown a tiny room with two torches in which, like Zelda in the Legend of Zelda, she must spend the rest of her life. Yet Azalea rejects this position. Instead she chooses something unknown, something that lies beyond the clouds, far from anything she has ever known. The people of her hometown might say she kidnapped herself, might tell stories of how she was taken away by evil, by the pig thief. How she was corrupted, foreign, unclean. But in reality, Azalea does what Zelda could never do. She saves herself.