Few games have the same magical ability to upset everyone and ruin relationships as Monopoly does. Every session is an exercise in cruelty, backstabbing, and resentment. Maybe the joke that no one ever communicated to me was that the title also referred to how the “fun” was allocated in the game. So who invented this insidious game? What cold-hearted bastard created a game that is actually designed around the premise that one person will accumulate all of the wealth and fun and do so by driving their friends into financial ruin?

It turns out that it wasn’t the Parker Brothers. It also turns out that the Parker Brothers actually are real people, unlike Betty Crocker. Furthermore, it turns out that it wasn’t Charles Darrow, who Google told me invented it. In the end it was someone named Elizabeth Magie who started it all. It took a conversation with indie developer Untame’s Julia Keren-Detar for me to realize the strange history of early American board games.

it was someone named Elizabeth Magie who started it all.

Keren-Detar has been studying board games for a while now, enough so to become an expert in the field. But her research hasn’t just been who invented Monopoly. She’s been digging deep into early American board games with the help of New York’s Strong National Museum of Play and has discovered a complicated history of some of the games we see for sale all the time.

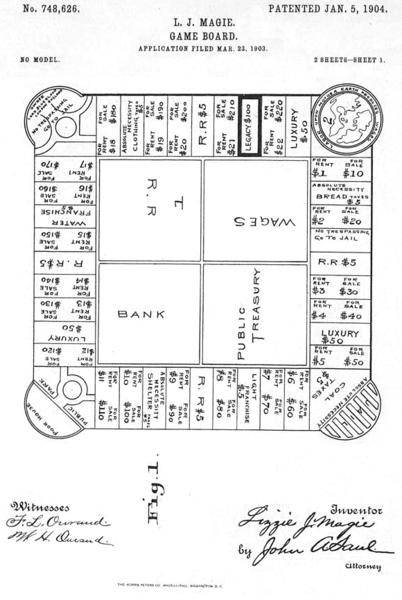

Take, for example, Monopoly. There’s a reason for its confrontational design, and it’s deeply rooted in the story of its invention. Elizabeth Magie was not a Carnegie or Rockefeller-type industrialist with a die habit, as you might imagine, and she didn’t precisely invent Monopoly. What Magie did invent in 1904 was The Landlord’s Game, a game intended to demonstrate the ills of profiteering by owning property. Her specific interest was how landlords could gouge and oppress their tenants to the point of bankruptcy. In 1904, this was the procedural rhetoric—a micro-tool to demonstrate what was happening on a macro scale in cities all over the country.

However, players will discover the fun when you give them the tools and the rules. As The Landlord’s Game found its way into the hands of more and more players its nature changed. Instead of demonstrating the harsh realities of landlords and inner-city tenancy, players found joy in screwing over their compatriots. However, even though it’s clear The Landlord’s Game, or its derivatives which would eventually become Monopoly, were no longer serving their intended purpose, the heart of the game remained. It was still a game about the harsh realities of capitalism and that winning came at the cost of others.

This story is not anomalous, in the grand scheme of games. Unlike modern games, which have definite creators, early board games evolved over a series of years across many different hands and sometimes countries. Chess began as a very different game in India prior to the sixth century before it found its way across the world. As the game moved across all those different countries it changed so that the battle might begin sooner. Players had realized that while there is distinct pleasure in planning and preparation, the real heart of the game was the battle itself. In the end, it would take almost a thousand years for chess to become what we know today.

Interestingly, the evolution of board games to enhance the pacing is a Eurasian-centric mode. This is not to say that such evolutions didn’t occur stateside, just that a different type of evolution happened here. Instead of tinkering with the rules, Keren-Detar found, Americans preoccupied themselves with theming and re-skinning them. For example, take The Mansion of Happiness, the 1800s predecessor to The Checkered Game of Life. When The Mansion of Happiness came over to the US from the UK it remained a moralistic tale of living a simple life free of vice. Like The Landlord Game, it was designed to be instructional.

As the game found its way to more and more people, it changed—or, rather, they changed it. Unlike chess, these changes were primarily thematic and very few fundamentally altered the way in which the game was played until 1960, when most of the modern attributes were added, such as the cars and money. Instead, these “racing games,” as Keren-Detar calls them, were all essentially different coats of paint on the same foundation. This isn’t so hard to imagine when you consider that today there are hundreds of different types of “-opoly” games. One of the key differences is that those are all officially licensed products and in the early days of American board games each reskin was introduced as a totally new game, albeit with identical rules and objectives.

Unlike chess, these changes were primarily thematic and very few fundamentally altered the way in which the game was played

However, these reskins served an additional purpose—they changed with the times. As time went on, living a clean, vice-free life with a payment in the afterlife was no longer the dominant mindset. The reskins focused on topics varying from daily life to rags-to-riches stories and worldly pursuits such as in The Checkered Game of Life, and other derivatives, such as Messenger Boy. This change is also paired with increased industrialization and leisure time. As both of these increased, so too did the desire to see earthly rewards based on a lifestyle that conformed to rapidly growing American capitalism. Much like Monopoly, racing games rewarded players for becoming capitalists, the idea being that avoiding spaces labeled as “carelessness” or “dishonesty” would allow players, and by extension workers, to succeed in the open and accessible American capitalist meritocracy of the late 1880s.

Keren-Detar’s work, then, places play neatly in the context of American history, which is filled with stories of people who didn’t actually invent anything. Henry Ford didn’t “invent” the car so much as he popularized it; the Edison vs. Tesla narrative is another steeped in invention versus credit. Elizabeth Magie may have come up with the idea, patented it, and sold it, but it was Charles Darrow (whose claim was disputed even by Parker Brothers) who invented Monopoly, essentially only a more insidious reskin of her game. So next time you lose and flip the board and storm out of the room just remember: it was designed that way. And that’s as American as can be.

Monopoly Pieces image via woodleywonderworks on Flickr

The Landlord’s Game Patent imge via Brian0918 on The Commons