The secret history of the Legacy of Kain

At this point, the Legacy of Kain series is difficult for one unfamiliar with its twists to enter into. The last game, Defiance, was released in 2003; its predecessor is almost fourteen years old; Soul Reaver, the ambitious seed that sprouted into an almost impenetrable forest, was released for the original PlayStation; its predecessor Blood Omen is orphaned abandonware. Accompanying this generational regression is the sheer inconvenience of leaving behind the latest advances in graphics and sound to return to their more primitive counterparts: the farther we go back, the more rudimentary the graphics and the flatter the sound until we come to Soul Reaver and its monologues in monophonic or Blood Omen’s top-down 32-bit palette. The irony of being forced, like the series’ character Raziel, to delve into a decrepit past to discover a worthwhile narrative should not go unnoticed.

But the series has its merits, which have been dredged up from relative obscurity as examples of excellent writing, voice acting (featuring the late, great Tony Jay), and a story fertile with yet-unplumbed significance. The series regularly resurfaces as a game with uncommonly rich storytelling, character writing, and visual design. In short, it represents a maturity in game design rarely found in its day—the kind of art that dares to be different and complex and delights with its audience in its own elaborate script, arc, and themes. But when Nosgoth, the online multiplayer battle game set in the same series, was announced, it was obvious that this newest game was a very different beast from its brethren. There was an almost tangible sense of betrayal—not merely over the expectation that the next Legacy of Kain game would complete the story, but over the way in which this latest game lacked some essential quality present in all the others. Ironically, Nosgoth still manages to fit within the series as a whole despite its differences, despite the way in which the game lacks so much of the complication that made Legacy of Kain so compelling: its lore and its themes.

To start, the gnostic elements within the story are frequently invoked but rarely explored in depth. Gnosticism is an ancient monotheistic religion, stemming from early Christianity, that believed that this world was created by either the fall or the malevolent act of a corrupt demi-god, known as the demiurge, that emanated from a unified divinity. Shunning the material world as inherently corrupt, gnostics embraced the spiritual world in a desire to escape the material and attain unity with the distant, perfect God. If this theology sounds abstract, consider The Matrix: the world of the simulation is a false one, created by malevolent machines for the sake of control. Neo and his ilk, like good gnostics, shun the simulation to pursue the real world because it holds the promise of truth and understanding.

this secret history is locked within murals and monologues, within sight and sound

The final reveal of the Elder God—the god of Nosgoth, the “still centre of the turning wheel, the hub of this world’s destiny”—as the series’ great villain fit neatly within the gnostic idea of the demiurge. But, with the wraith Raziel, the game neatly inverts the traditional gnostic division between imperfect flesh and perfect spirit by rendering the spectral realm as one of horror: it is a brutal ecosystem of predation and consumption as its monstrous denizens, the Sluagh and Raziel, feed on lost souls trapped within an eternal twilight. It is filled with discordant noises, whispers, and screams, and is colored by an omnipresent and pallid blue aura. The architecture itself is a twisted analogue of the material realm, as pillars twist into helices and walls warp and bulge as the player shifts between worlds. In contrast to this indigo nightmare, the material realm is the superior world: it is the world from which Raziel is exiled at the beginning of Soul Reaver and to which he is constantly trying to return as it is, simply put, where things happen.

The series’ emphasis on the material realm neatly mirrors the kind of knowledge that the player pursues: as gnostic is derived from the Ancient Greek gnosis, “knowledge,” so too is the gnostic aspirant’s goal one of spiritual understanding—but in Legacy of Kain, the knowledge sought is not spiritual, but historical. The series of revelations that occur are not abstract mystical truths, but concrete ones: the secret history of the vampire race, their primeval war with an ancient enemy, the creation of the pillars, and the promise of a future redemption are all testified to by the revelations locked within ruined temples and citadels. Even the transmission of these epiphanies emphasizes the material and the sensual, as this secret history is locked within murals and monologues, within sight and sound.

This emphasis on history helps to explain why the series’ narrative is so complicated. History is fallen, according to Kain, and perverted from its true course. When, in Soul Reaver 2, he and Raziel stand in William’s chapel and reshape the course of history, Kain says as much: “I was ordained to assume the role of Balance Guardian in Nosgoth, while you were destined to be its savior. But the map of my fate was redrawn by Moebius, and so in turn was yours.” The story of the last two games—Soul Reaver 2 and Defiance—then becomes the process of rectifying history, of restoring it to its proper flow. Put another way, the return of the soul to its proper, divine status is the objective of vanilla Gnosticism; in Legacy of Kain the objective is the restoration of history’s proper flow. That the series’ narrative is marked by paradoxes and constantly shifting timelines complicates the story, but the rewriting of the plot represents the process of historical redemption. Indeed, it may be useful to understand the story of Legacy of Kain not as one long and knotted narrative, but as a shorter story working towards its most true telling.

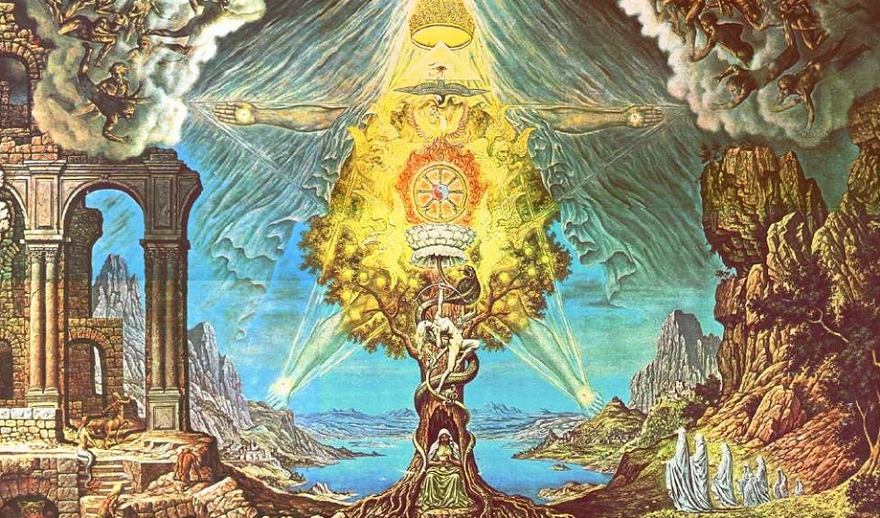

To continue unwinding the game’s gnostic allegory, we can see how Kain is the deity figure set in opposition to the Elder God by noting the links between the series and the Kabbalah, a structured system of Jewish mysticism. The narrative of the original Soul Reaver game has Raziel hunting Kain by defeating his children. To rephrase this in a more pointed fashion, Raziel pursues his creator by navigating Kain’s

emanations. Both this structure and Raziel’s very name—a name meaning “Secrets of God” in Hebrew—invoke the Kabbalah, where God sustains the world via a series of emanations or manifestations and the aspirant must travel up this system in order to attain understanding.

To simplify things, the hierarchy of emanations is often depicted as a kind of map, known as the Sephirot or the Tree of Life. The lowest point on the map is the material world—known as Malkuth, a name cognate with that of Soul Reaver’s first boss, Melchiah—and goes up through different points, ultimately reaching God. That Raziel must confront the lowest of Kain’s children first and ascend up the hierarchy cements the parallel between his quest for revenge and the Kabbalist’s quest for enlightenment. That Soul Reaver’s hierarchy is a dark caricature of the Kabbalah’s more beneficial ordering tells you what you need to know about the world of Nosgoth: it is a twisted, festering place, an aesthetic reinforced by its gothic architecture, its monstrous inhabitants, and its lonely, discordant background music.

Kain is the god of this material world—the first line of Soul Reaver is “Kain is deified”—and the power ultimately set in opposition to the machinations of the Elder God. Kain is repeatedly depicted as in the know regarding Nosgoth’s secrets as he sets Raziel on his own personal journey of revelation, of gnosis. But Kain’s own story sees him, at last, in confrontation with the Elder God. In this pairing we too see the game’s reversal of the traditional spiritual and corporeal binary inherent to Gnosticism: it is Kain, heir to the material realm of Nosgoth and its history—who deals in blood, not souls—that is the, for lack of a better term, good power. In essence, Legacy of Kain’s occult narrative is a wonderfully dark inversion of its sources: the spiritual is a corruption of the physical, the holy is horrifying, and the secrets that are divulged are historical, not metaphysical.

In that vein, the grand climax of the incomplete series is the following realization on the part of Raziel at the end of Defiance:

All the conflict and the strife throughout history, all the fear and hatred, served but one purpose—to keep my master’s Wheel turning. All souls were prisoners, trapped in the pointless round of existence, leading distracted, blunted lives until death returned them—always in ignorance—to the Wheel.

Raziel’s epiphany establishes the overarching villain: not simply the Elder God, but the repetitive structure to which Raziel and the rest of the world is bound. The recurrent wars of extermination—vampire against hylden at first, and then human against vampire ad infinitum—are merely the permutations of a wretched, bloody pattern that defines history—and, as Kain says, “History is irredeemable.” Until, at the end of Defiance, it can suddenly be redeemed.

a gothic, bloodstained nightmare with no hope of redemption

The great irony at the heart of Nosgoth lies in how appropriate it is to Raziel’s realization at the end of Defiance. As a continuation of the story of the series, Nosgoth is a failure—but this is not the rubric against which the game sets itself up for judgment. Instead, it is merely another instance of “All the conflict and the strife throughout history, all the fear and hatred” that Raziel speaks of in Defiance’s climax. In other words, it is supremely fitting that a series defined by a recognition of the essential part conflict plays in the world should, in its latest incarnation, focus on that conflict. After all, to those familiar with the series’ secret history, Nosgoth is how the world looks to those uninitiated into the mystery: a gothic, bloodstained nightmare with no hope of redemption to be found.

Here we get to the heart of players’ dissatisfaction with Nosgoth. At the end of Defiance, there was a promise of true revelation: “Now, at last, the masks had fallen away. The strings of the puppets had become visible, and the hands of the prime mover exposed.” That last gift of Raziel, the “terrible illusion—hope” was felt by Kain and fans of the series alike: hope that some conclusion might be reached, that the final, true draft of the story might be attained. Instead, players were thrust back into the game’s irredeemable history of conflict. Nosgoth’s developer, Psyonix, cannot be faulted for their enthusiasm and dedication to the atmosphere of Soul Reaver, but when a final gnosis is at hand, who would not be bitter over a return to ignorance?

This is not to say that Nosgoth is a bad game—it is quite the opposite: the asymmetrical gameplay is fun to participate in, whether you play a vampire or a human. Furthermore, Psyonix have shown repeatedly in the game’s various visual cues that they care deeply about their source material. But in many ways it represents a step backwards for the series: a return to the world of the original Soul Reaver is a literal step backwards in the story, a return to a previous iteration of a false history. The recent reveal of the cancelled Legacy of Kain: Dead Sun similarly triggered a sense of disappointment and betrayal over the lack of a definite conclusion to Kain’s story. A return to Nosgoth is not necessarily always welcome: only the attainment of that final gnosis will satisfy us.